Why Is Moscow So Weird?

Moscow is the biggest city in Europe. How come?

It’s one of the northernmost capitals in the world, yet away from the warming influence of the sea. Why?

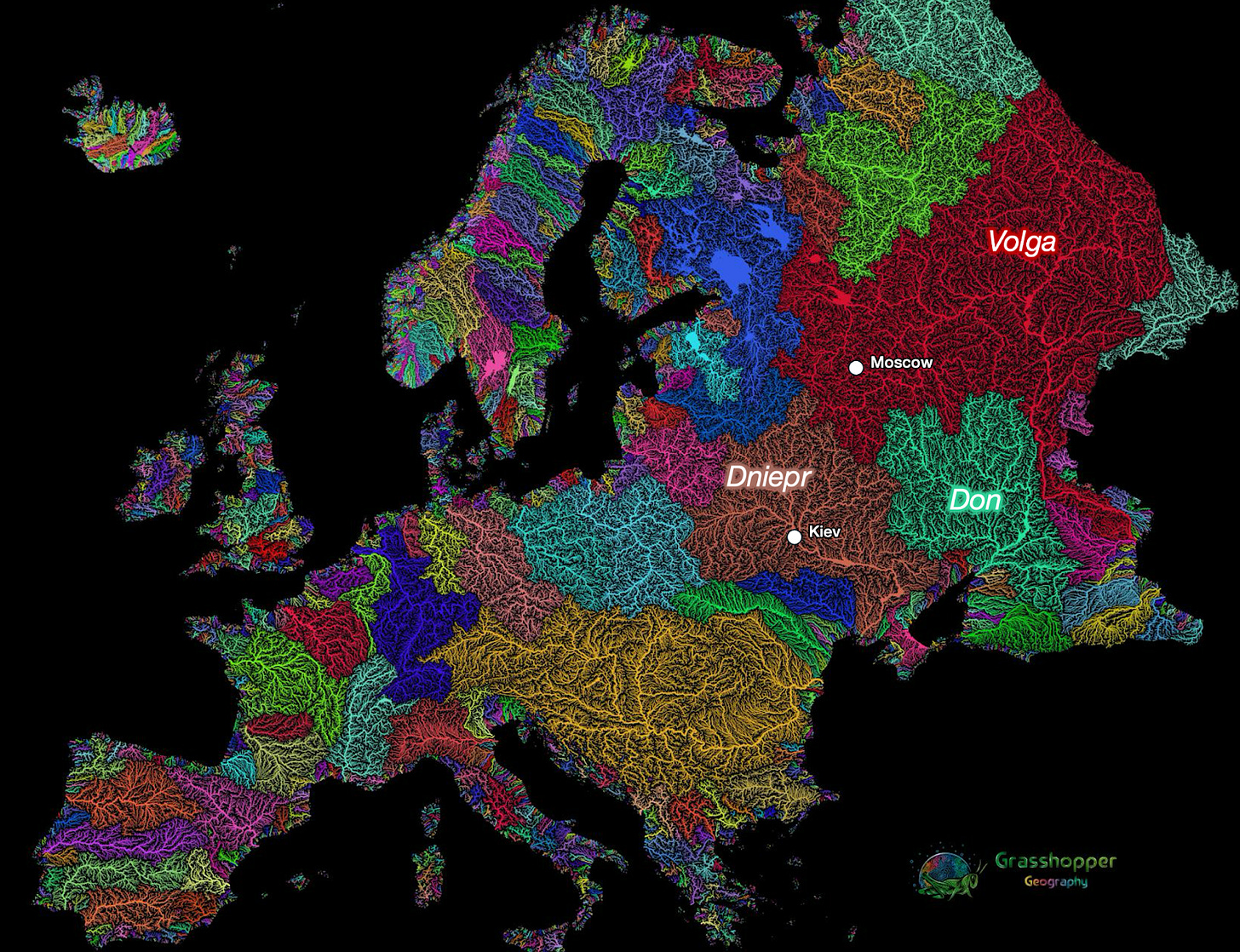

Most European capitals are on a major river, but Moscow is on a tributary of a tributary of a river that ends in a lake.1 And while most other big cities are on river confluences, Moscow isn’t. Why such a poor location?

At over 17,000,000 km2 in surface area, Russia is by far the largest country on Earth.2 Of all the possible places it could have a capital, why did it end up being in Moscow? A city so far to the west of the country, on a tiny river, far from the sea or any trade hub?

You might retort: It’s so far west because it conquered everything to its east.

But that doesn’t really answer the question. Why was it able to conquer all that territory to its east? No other country has done anything even remotely similar. Why could Russia? And how is it possible that it would reach the Pacific Ocean before it reached the Baltic or the Black Seas?!

And why is Russia’s capital not on the Volga, the longest river in Europe? The capital could be Volgograd (“the city on the Volga”), previously known as Stalingrad.

Why isn’t it Kiev, an older city than Moscow, in the middle of the most fertile area in the region, and the capital of Kievan Rus, a predecessor kingdom to Russia today?

Why isn’t it Novgorod or St Petersburg, cities that are much better located for trade, on the Baltic Sea?

Why isn’t it in Novosibirsk, much more centrally located?

How did Moscow evolve from a swampy3 village in the 1100s to the biggest European city with over 20M people?4

An AI rendering of a Medieval swampy town on a river turning into Moscow.

The answer to all these questions is pretty crazy. It involves horse archers, human harvesting, and tiny animals, and it tells us a lot about Russia’s past and its future.

Not Too Cold

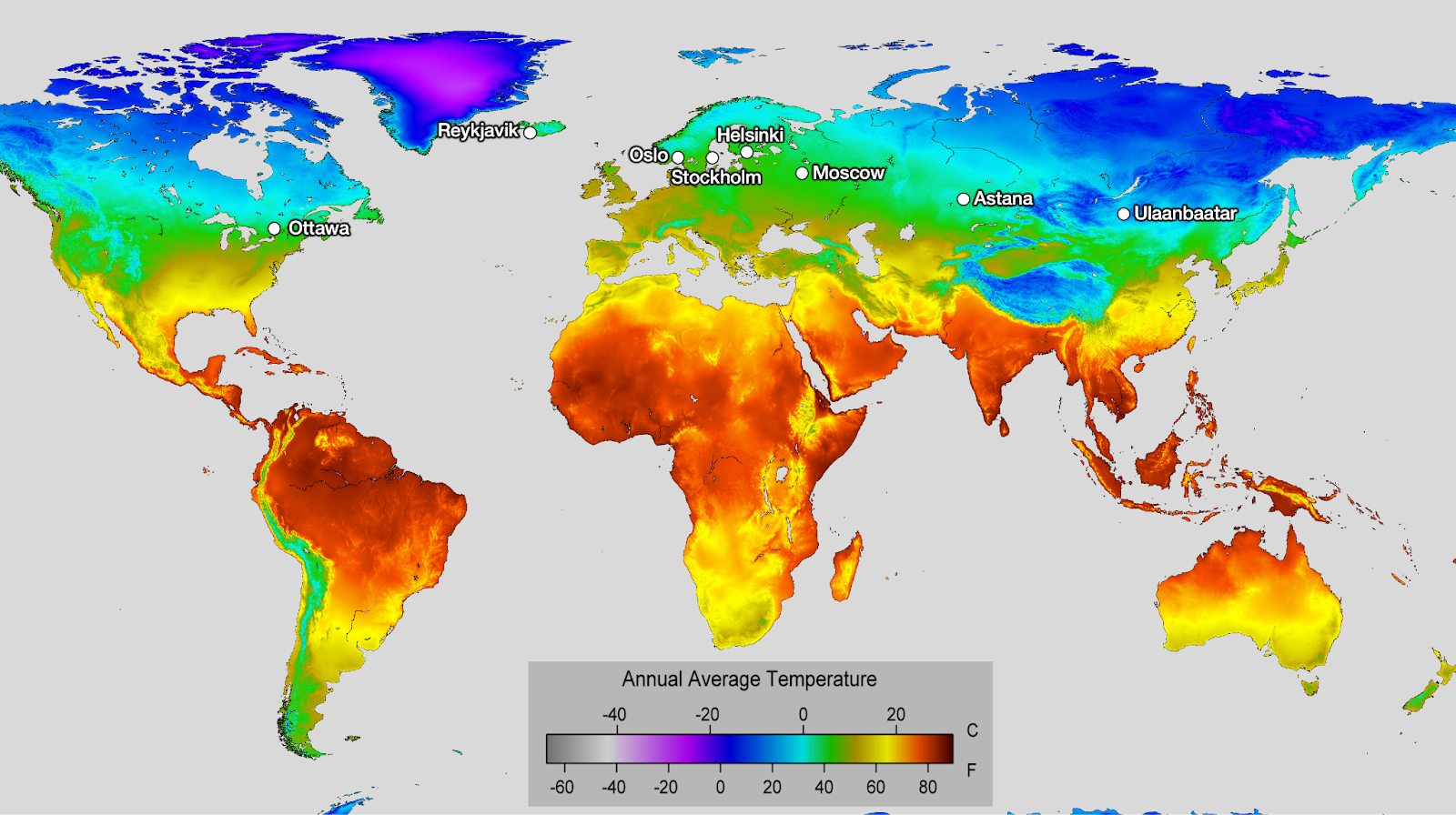

Russia’s capital is very far north. It’s the 3rd coldest capital on Earth,5 and by far the biggest, at 8x the size of the next one.6

It’s so far north it barely has farmland!

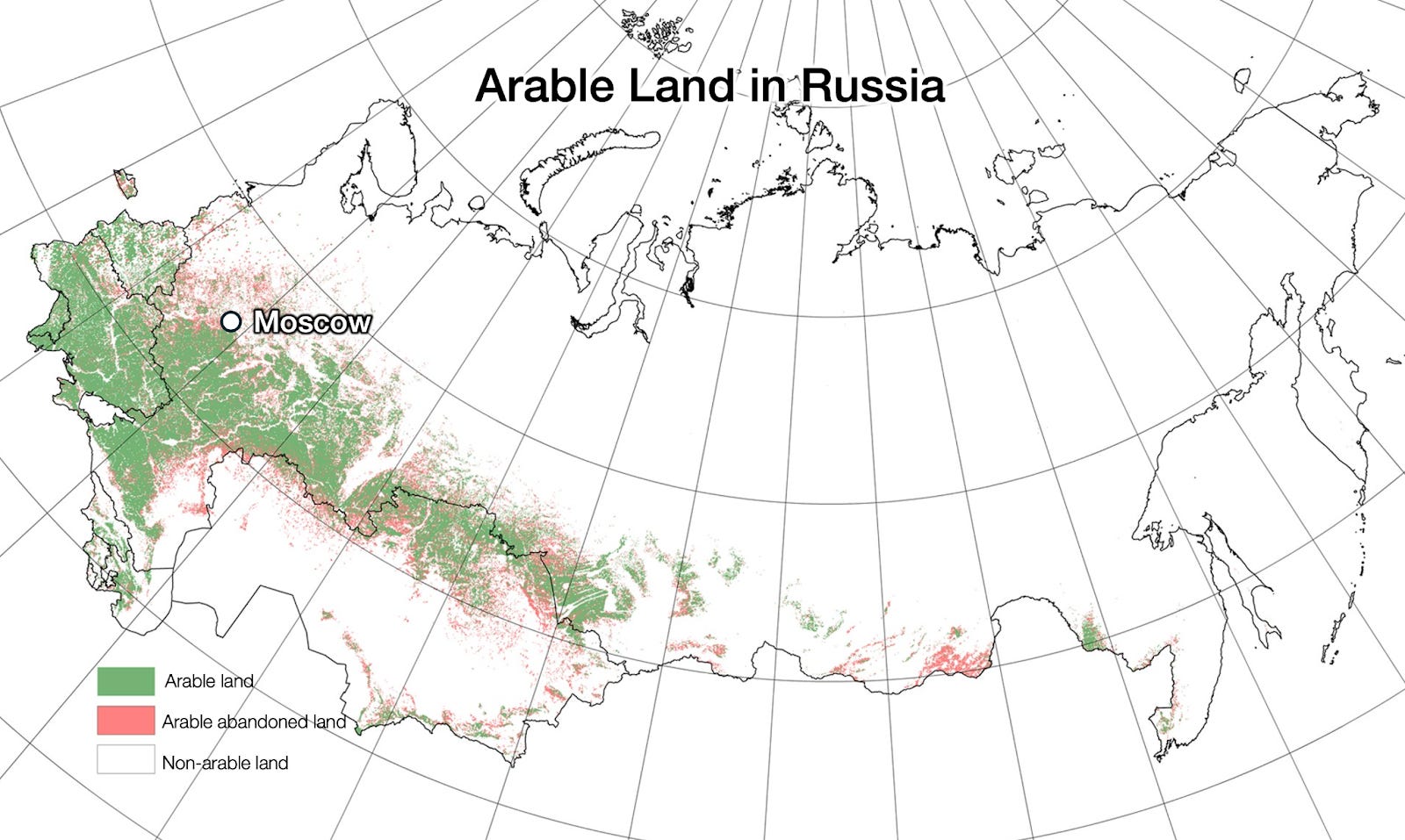

Why would you put the capital of the biggest country on Earth on the edge of some of the most fertile farmland on Earth? Capitals need a stable source of food. That usually means farms, or at least a port to import food.7 Moscow is not on a sea port or a major river (we’ll see why later), so it needed farmland to support it. This limits how far north Moscow could be, and it’s pretty much as far north as it can get away with.

Moscow sits in woodlands, and the taiga forest begins north of it. None of this is very conducive to farming. So weird… It’s as if Moscow was trying to escape from fertile southern lands… That’s exactly what happened.

Escaping from the Southerners

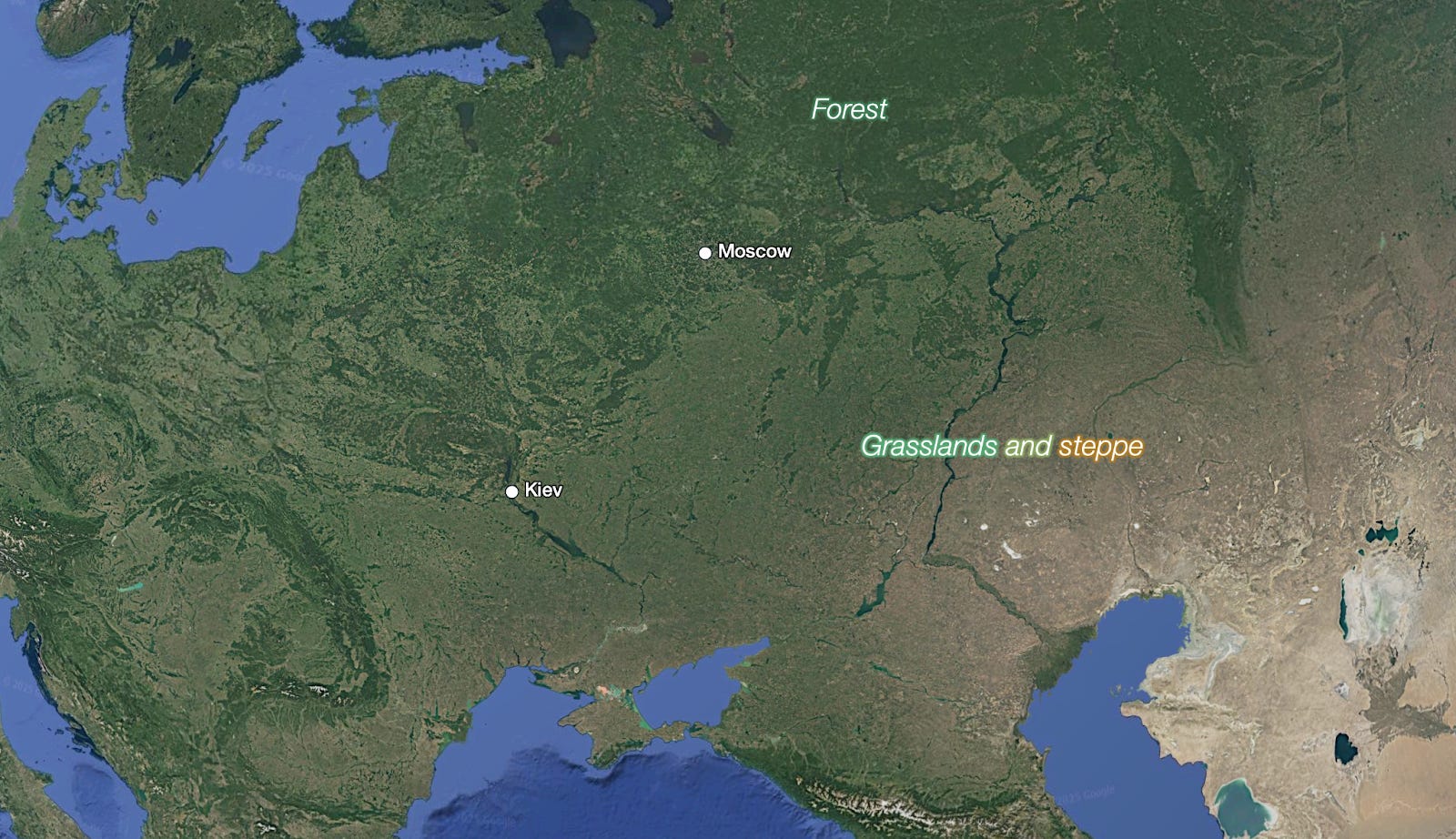

You can see in the maps above that Moscow is north of today’s cropland area, and south of that are grasslands. Why grasslands? Because there’s just not enough rainfall to sustain a forest or crops.

And who lives in grasslands?

Nomadic Lifestyle

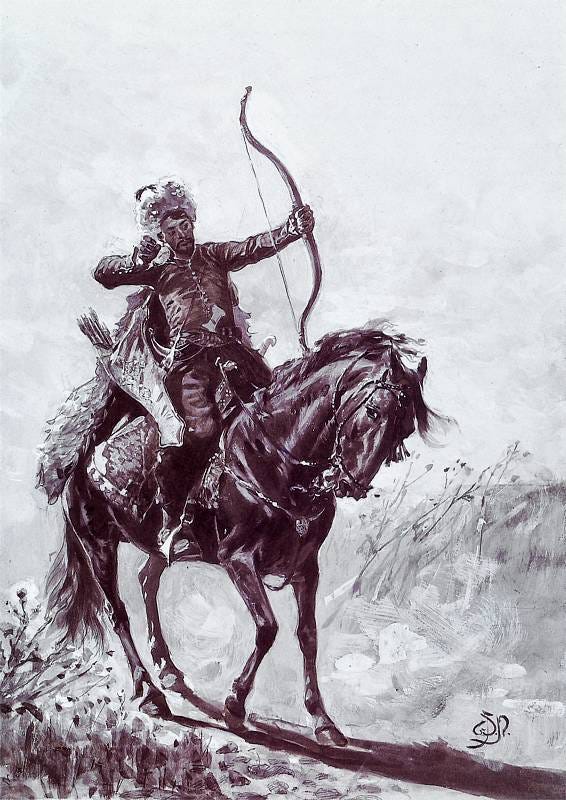

Steppe societies are perfectly suited to live in grasslands in a way that no other society is:

Grasslands can’t sustain agriculture without irrigation. In other words, the ground can’t produce enough calories for humans to survive.

But nomads can roam! So they can consume the calories produced across a larger area of grasslands.

This way, they can feed horses, goats, and sheep. They then feed themselves from these animals’ dairy and meat. To give you orders of magnitude, a sheep can feed 100 people for one day, so just 30 sheep are enough meat for a company for a month.8

These animals also gave them wool, leather, furs, and bones for their clothing, weapons, armor, and yurts.

They are extremely mobile. If needed, they could travel up to 100 km per day. Riders had several horses (usually 5-6 mares) and would mount each one in turn to avoid tiring them too much.

This meant they could quickly scout large areas, find weak points, and gather numerous riders there to overwhelm the enemy.

The enemy couldn’t easily retaliate because the nomads would simply withdraw faster than they could chase them.

This is how the Mongols were able to build the biggest empire the world has ever seen in just 70 years.

And how did they treat farmers on these lands? Not very nicely.

Steppe Hordes Are Not Nice

The vast expanses of the Eurasian steppe begin about 200 kilometers south of Moscow, stretching from the Carpathians to Mongolia. These black earth soils are perfectly suited for settled agriculture but were mostly uninhabited by peasants up until the mid-17th century, because of the constant threat of nomads’ raids.

The most durable threat came from the Crimean Khanate – a successor of the Golden Horde and the Mongol Empire, and a vassal state of the Ottomans from the late 15th century. The slave trade was one of the main income sources for the Crimean nobility, and an important economic support for the mostly pastoral population. Skilled Crimean horsemen “harvested the steppe”9 by capturing peasants on the Russian, Ukrainian and Polish frontiers, and brought them to the Crimean port of Caffa (modern Feodosia) for export to the slave markets in the Ottoman Empire.

About three million people were captured from all the Slavic lands (Russia, Ukraine, Poland) in the 15th and 16th centuries. About 200,000 people were abducted from Russia in the first half of the 17th century.—All Along the Watchtower: Military Landholders and Serfdom Consolidation in Early Modern Russia, Matranga & Natkhov, 2025. The following quotes are from the same paper.

200k people is about 3% of the Russian population at the time!

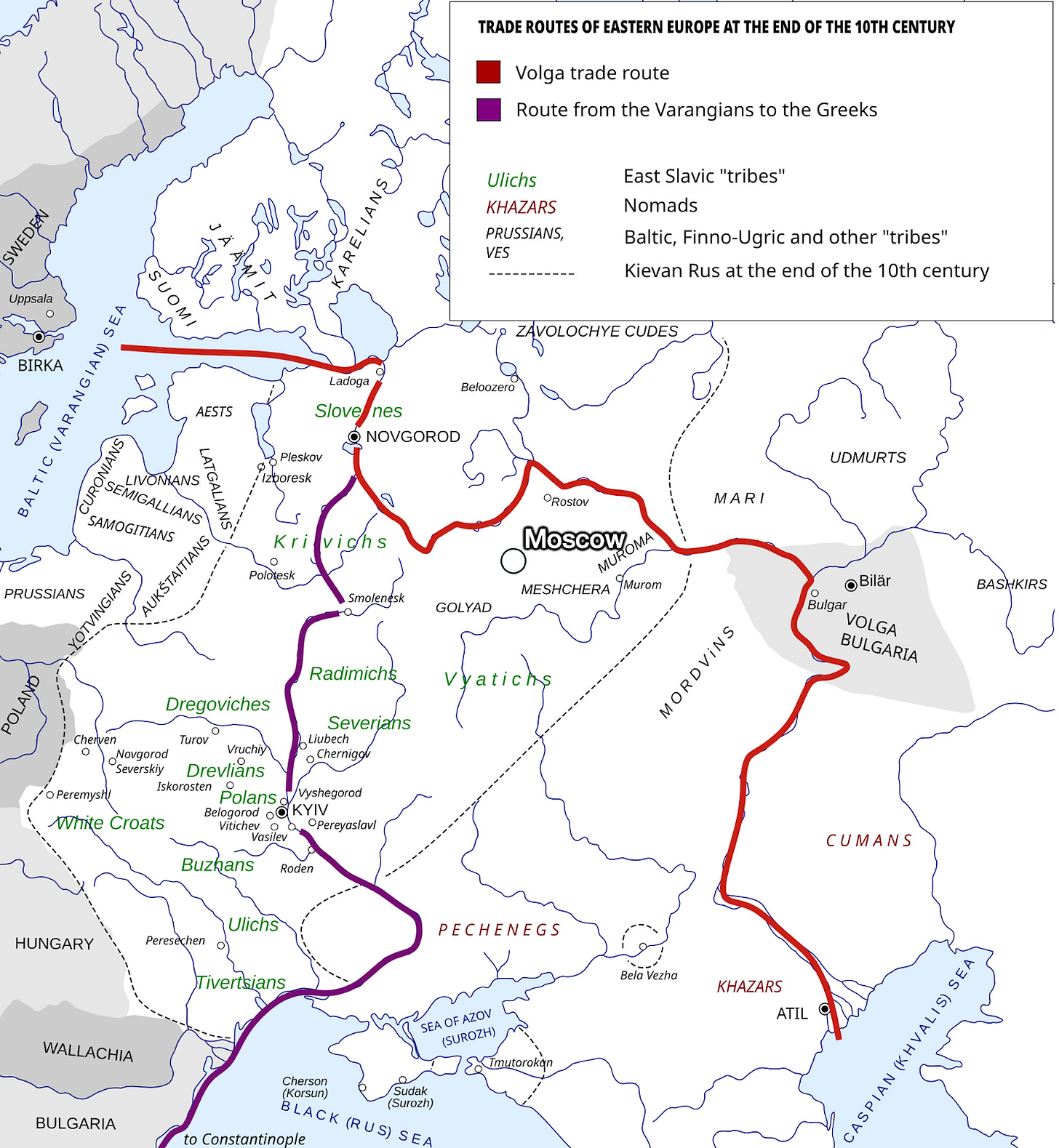

With a threat like this, you’d want to attack the enemy to stop their raids… but you can’t. With these types of raids, no farming village could survive. The kingdom of Kievan Rus (the oldest Russian kingdom was based in Kiev10) disappeared because, although it was rich from farming its lands and trading with Byzantium, it was constantly attacked by steppe hordes until the Mongols steamrolled Kiev. Ukraine could have been a superpower, if not for the steppe hordes.11

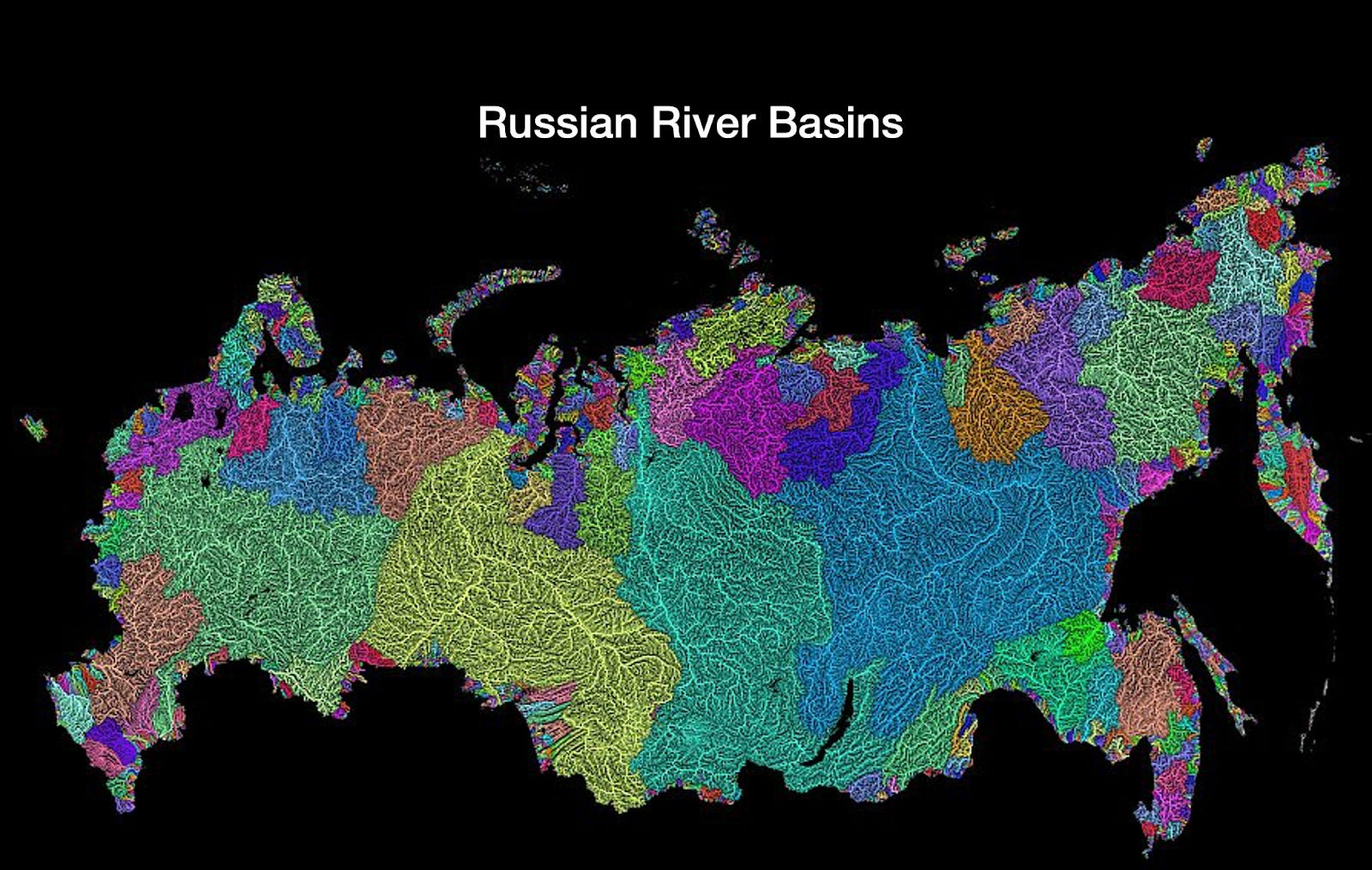

The steppes were a difficult area for the Russian army to campaign in due to logistical problems. Food could not be acquired from local peasants since they did not exist,12 nor could it be brought by river from populated areas, because the steppes are drained by rivers that flow into the Black Sea, while Central Muscovy is part of the Volga drainage basin, which empties into the Caspian Sea.

Any transportation across the two watersheds would necessarily include slow and expensive portaging across the divide. Furthermore, since Moscow was on the defensive, they had to deploy and feed the guard forces whether nomads attacked or not.

In contrast, the nomadic way of war was perfectly suited to the open and sparsely populated conditions of the frontier. From their winter pastures along the Black Sea coast, raiders would venture north as soon as the spring mud season receded. The scale of the raids could range from a few dozen members of the same extended family to tens of thousands of horsemen. In addition, the raiders could decide when and where to attack, unlike the Russians who had to be constantly prepared for the defense of any part of the frontier. If a location was strongly defended, a band of nomads would seek to distract the Russian army, while others took captives undisturbed.

So it’s not like some king decided to go to Moscow because it was a perfect spot to create a capital. Rather, the alternatives to its north were too cold, and the thriving alternatives to the south were eliminated by steppe hordes.

The band Moscow finds itself in was ideal, because the steppe stops about 200 km south of it, so nomads didn’t have grasslands to feed their animals as they approached. Forests also slow them down, make archery less effective, and provide plenty of wood for protective structures like walls.

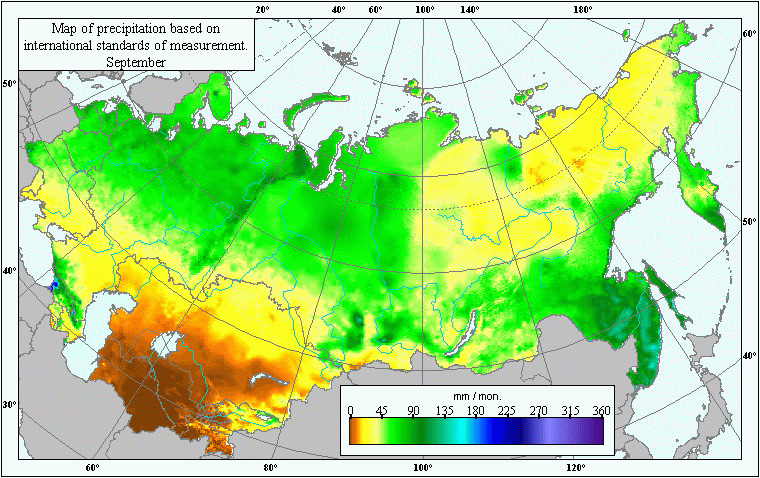

This is at the edge of what steppe hordes could reach: Grasses grow with sunlight, so in winter, they don’t grow as much. Nomads had to spend their winters in southern pasturelands close to the Black and Caspian seas.

Travel too close to the winter could be impossible, because the rains create the Rasputitsa (mud season):

Nomads had to raid the north mainly in the summer, and it took about a month to reach the area of Moscow and a month to return, leaving them little time to raid; it was about as far north as they could reach. Moscow didn’t need to defend itself for months on end, it just had to hold off the enemy a few months per year.

Nomads could still reach it, though. Also, the band of southern woodlands stretches for thousands of km east to west. What did Moscow have that was special in that band?

River Walls

Across the Eurasian Plain, most rivers flow north-south.

It’s inconvenient when your enemies can also flow north-south on horseback because rivers can stop horseback riders, but not if they run parallel to their path!

You need an east-west border formed by rivers. You need…

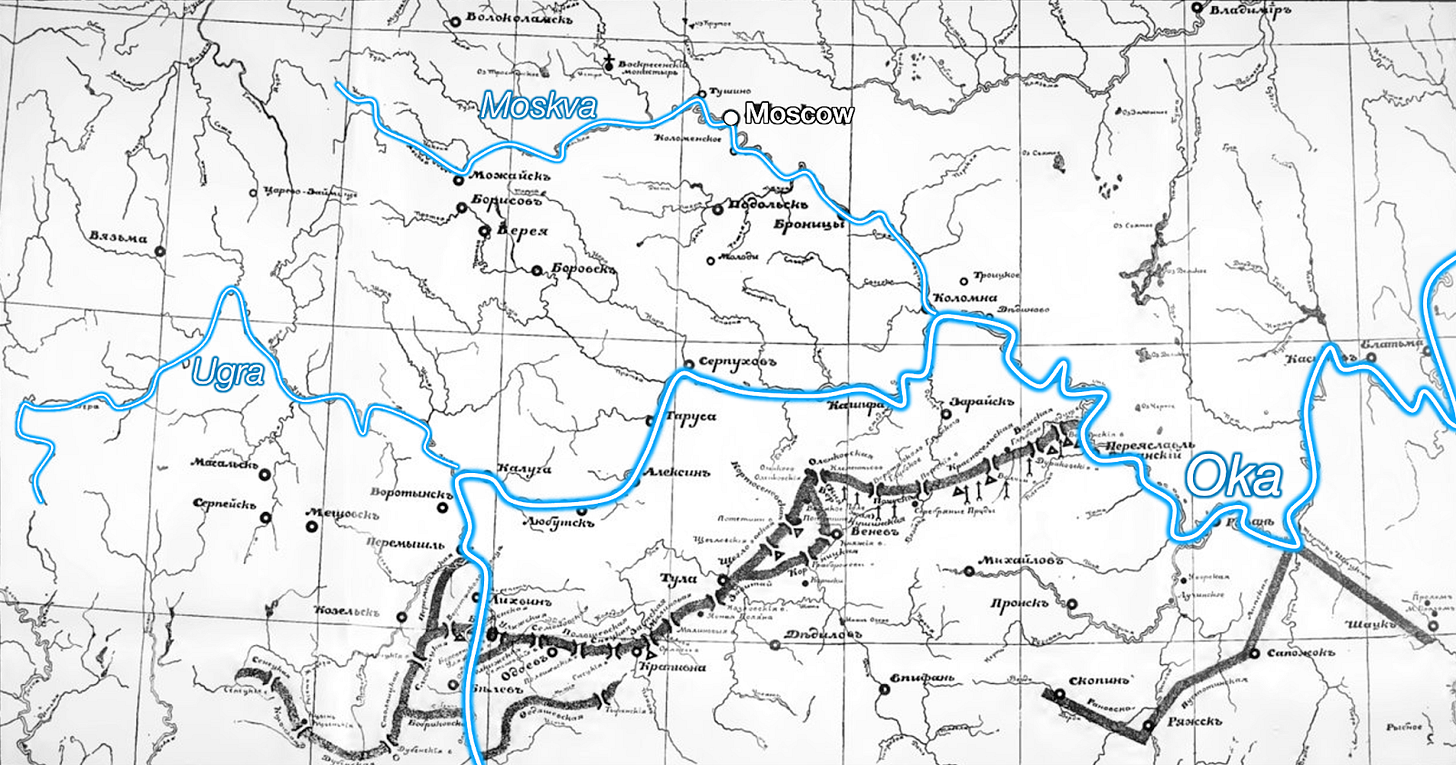

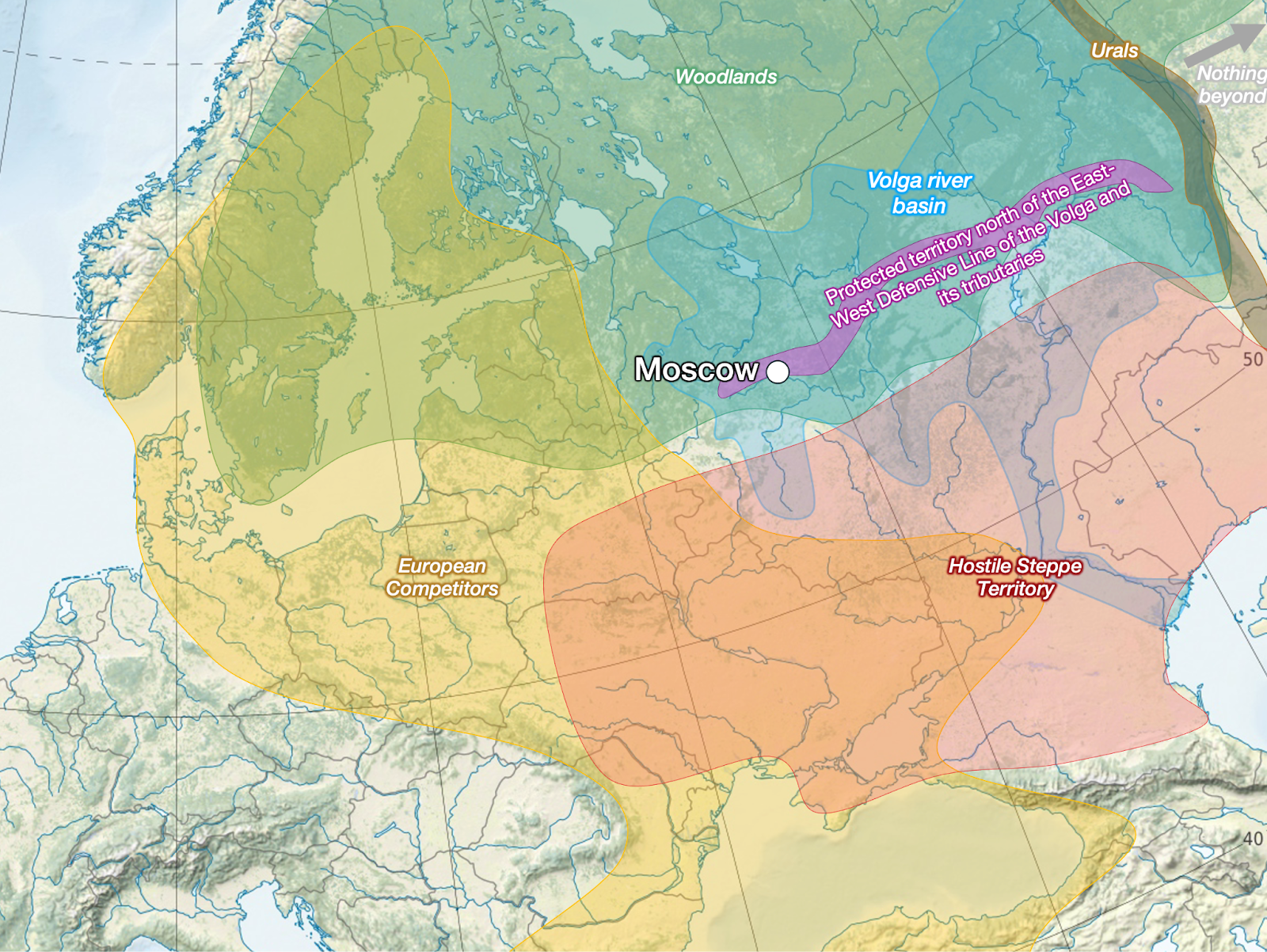

To its north, the Volga bends westward, forming a strong barrier with its tributaries: The Kama and its tributaries reach the Ural Mountains to the east, and the Oka and its tributaries the Ugra and Moskva reach far westward. And where is Moscow?

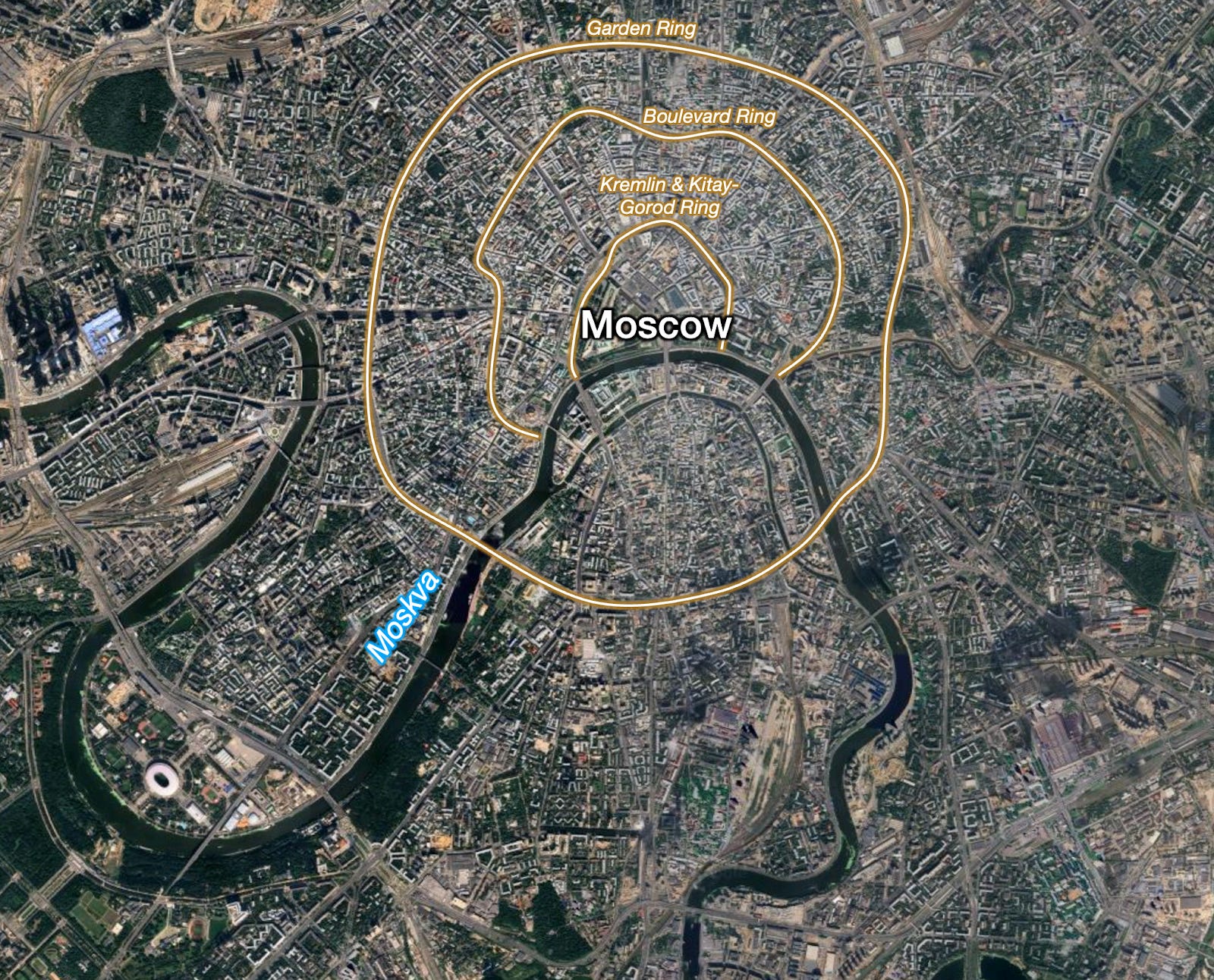

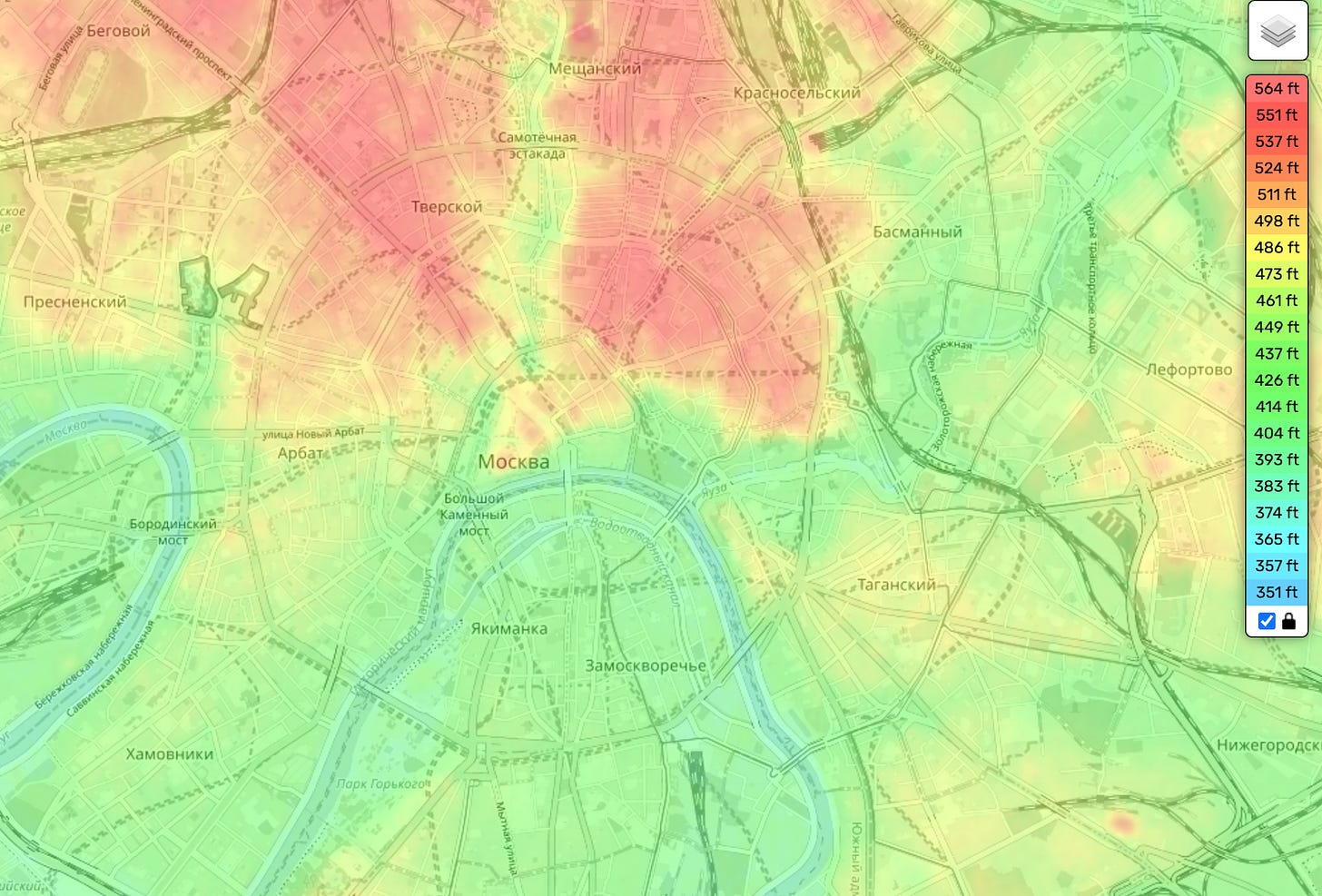

Moscow’s historic center is on the north bank of the Moskva! That way, the river protected it from the threat of southern hordes. Moscow built several concentric walls as it expanded outwards, which you can easily see on satellite maps: Like in many other cities, these are now highway rings or boulevards.

Of course, and like in many other cities, this specific point of the Moskva is convenient because the Kremlin could be built on a hill, making it easier to defend:

But this was just the last line of defense. Moscow also had to defend all the surrounding countryside that provided food, wood, and revenue. And this position along the Mokva is ideal because there’s another natural line of defense to its south: the Bereg Line (Riverbank line) along the Ugra and Oka rivers, which cut the invasion axis from West to East. So Moscow constructed a series of fortification lines similar to the Great Wall of China and the Roman Limes from the mid-16th century.

Its strategy was simple: Garrison the Ugra-Oka line so as to block all possible fording locations, repel any river crossing attempts, and wait for the campaign season to draw to a close.

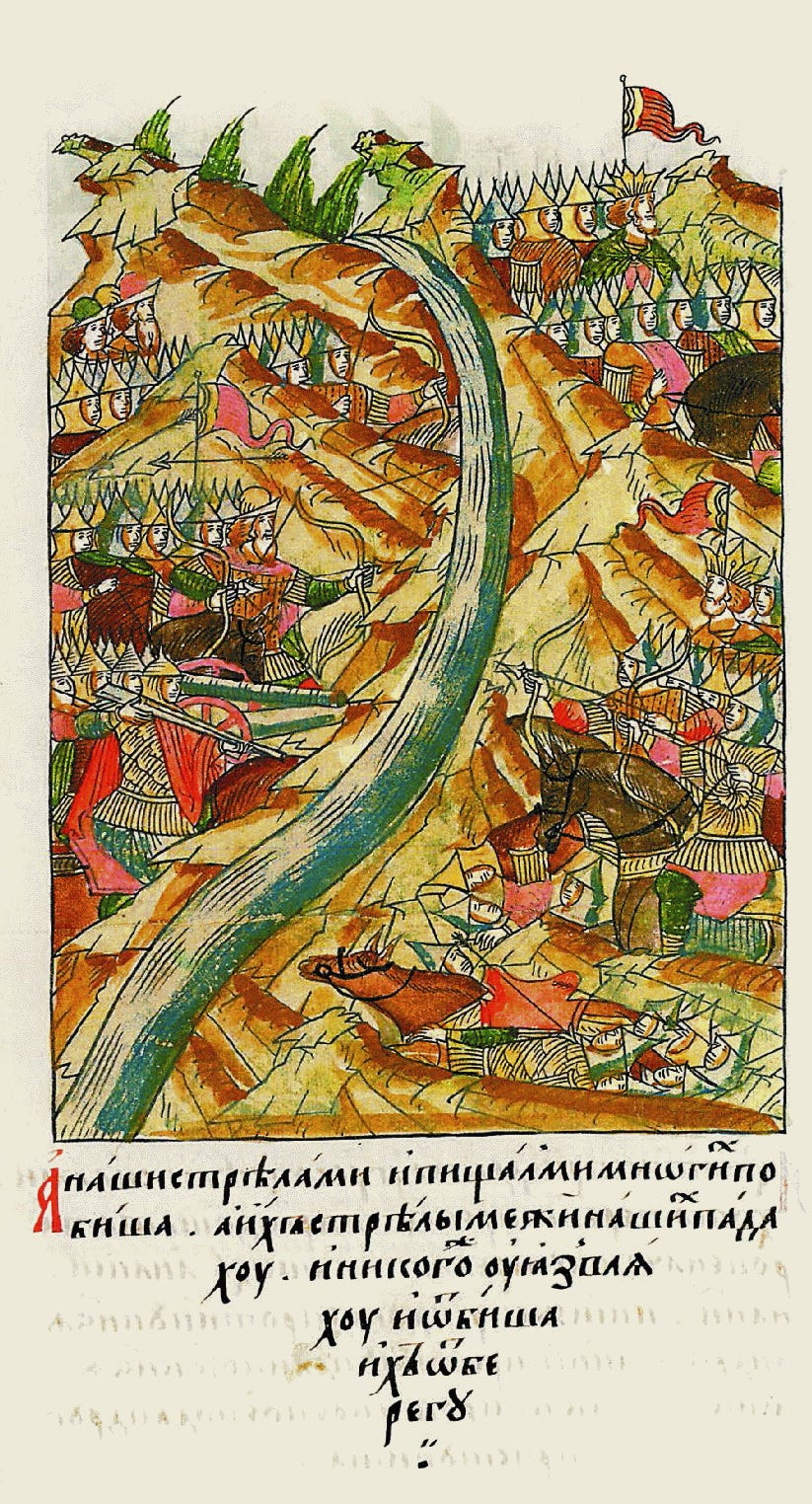

The first time Moscow achieved this was in The Great Stand on the Ugra River, in 1480:

Moscow’s Ivan III was able to garrison every possible ford on the rivers, and stopped the southern nomads. As winter approached and the rivers started freezing, he retired his forces towards Moscow, to ambush the nomads in the forests. This additional buffer was too much, and the nomads turned around in November.

This is a perfect illustration of Moscow’s ideal position: In the wooden range, south enough to get some farming but north enough to delay the steppe nomads, and behind the natural barrier of the Volga – Oka – Ugra –Moskva rivers.

But this is not enough: Moscovites got lucky that year, but nomads could try this every year. They only needed to get lucky once in order to sack Moscow, so in the 1500s, they tried to raid Moscow 20 times! They succeeded a few times, notably in 1571, when Moscow was burned, its population shrunk from 100k to 30k, and nearly 150k people in the region were taken as prisoners for the slave trade!

Moscow needed a deeper defense. So it built it.

If you’re keeping count, that’s three lines of defense at this point.

To avoid the possibility of a single point of failure and to expand the protected area, a new line was built some 50-100 km to the south. The Great Abatis Line (Bol’shaya zasechnaya cherta), also known as the Tula defense line (Tul’skaya cherta), was a chain of fortifications erected until13 the 1560-s about 180 kilometers south of Moscow. The line was built from felled trees laid in a row with the sharpened tops towards the enemy and augmented, where possible, by earth mounds, ditches, and watchtowers. The line was a formidable obstacle since it deprived the nomads of their main tactical advantage – mobility. By 1630, the line consisted of about 40 fort towns and stretched for more than 500 kilometers in the east-west direction. This type of fortification could be quickly built in forest areas. Aside from being an obstacle for nomads and a natural shelter in case of unsuccessful defense, forest was the main source of construction material. This explains why the southern border of Muscovy did not advance past the forest-steppe boundary until the end of the 16th century.

Wherever it could use existing rivers, it did. Elsewhere, it built wooden palisades thanks to the available forest around. Since this area had no farmers due to previous raids, Moscow needed to send soldiers there and feed them for months. That was too expensive, so it granted lands north of it to the soldiers that would defend it. Interestingly, this was the origin of Russia’s serfdom, as described in Matranga and Natkhov’s amazing paper on the topic, which inspired this article.

You can see this on the map of Russia’s expansion:

Northern Expansion

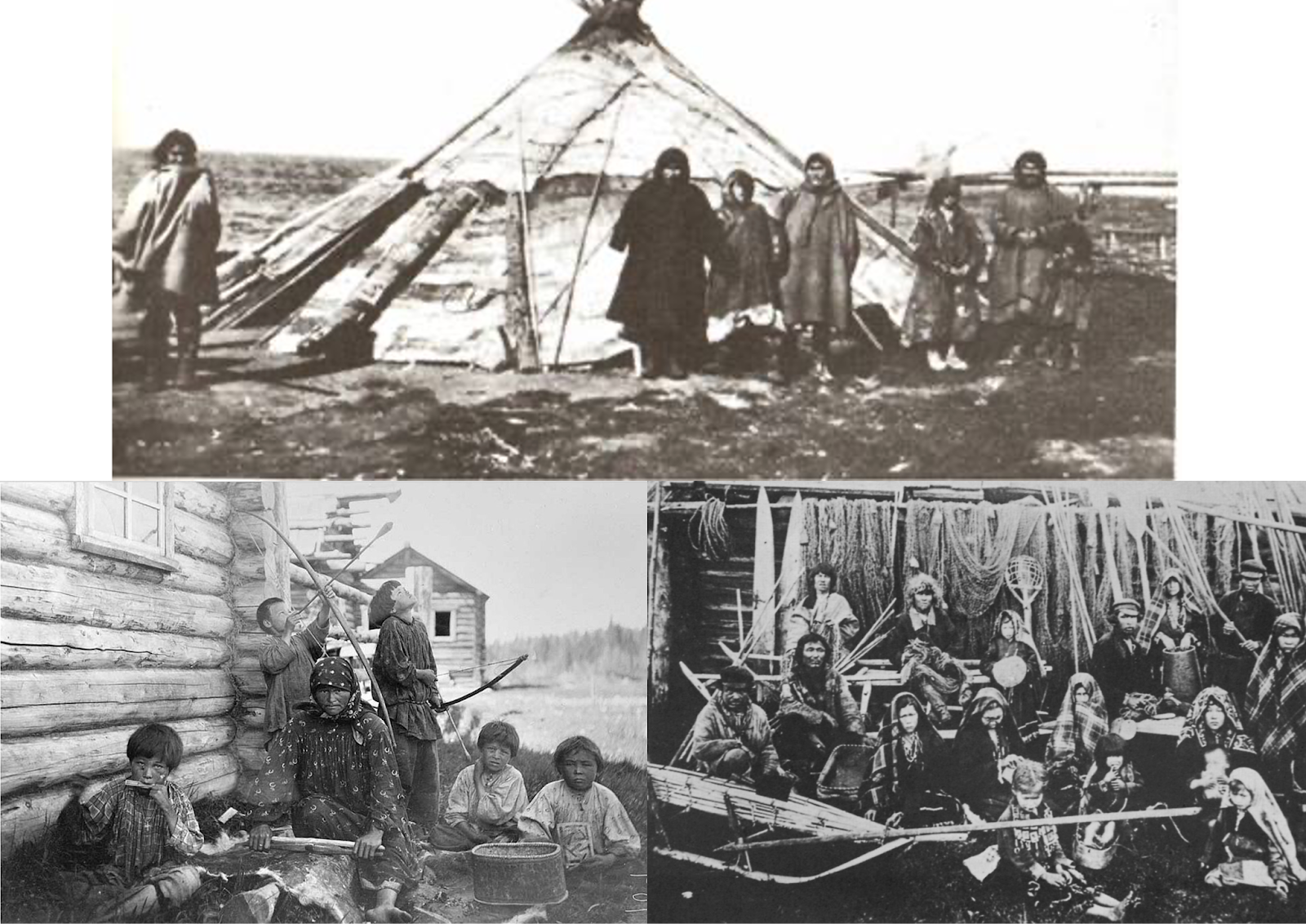

First, from 1300 onwards, the Duchy of Muscovy expanded northwards. Why?

Sure, it was so cold that nobody else could challenge Moscow in conquering that area. But the fact that it’s too cheap to conquer doesn’t make it worthwhile. Aside from low cost, Russia needed a benefit. What do you think that was? What kind of wealth can you get from a landscape like this?

You get this:

The fur trade was mostly of small squirrel-like animals called sable.

It was controlled by Novgorod, which was connected via rivers to the Baltic.

Unfortunately for Novgorod, it’s close to Moscow, and on the path to the river trade routes between the Baltic and the Black Sea.

Moscow had farmland to grow its population, whereas Novgorod didn’t. The result was that Moscow conquered Novgorod in the 1470s. This is basically the exact same reason why Britain was able to conquer Canada in the 1700s: Canada was dedicated to fur trade so its population was small, while the British Colonies were farmers, so their population was much larger.

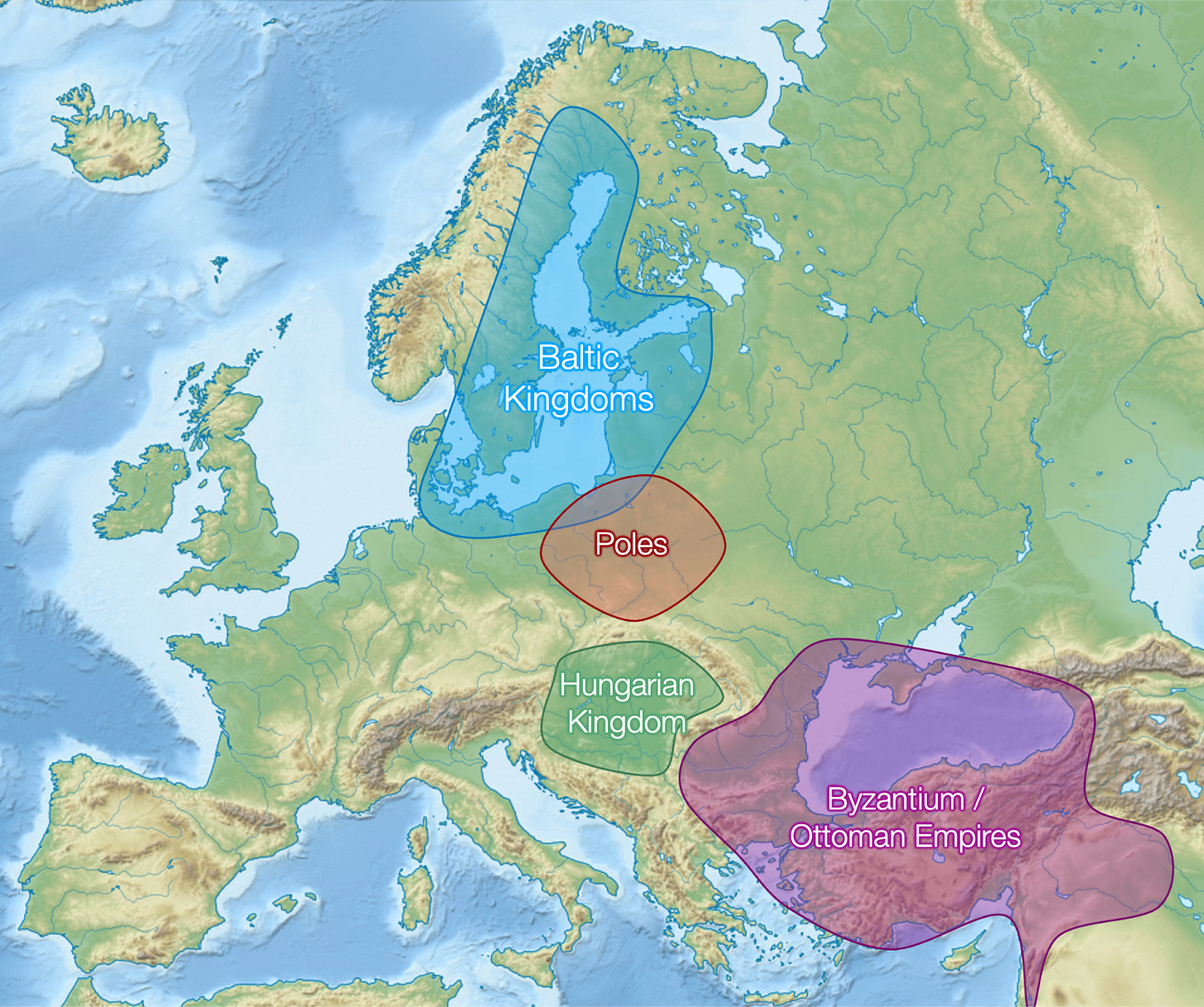

Note that, although Moscow could trade with the Baltic, it avoided actually controlling any land on the Baltic Sea itself, because there it was exposed to powerful kingdoms like Denmark, Poland-Lithuania, or Sweden. Instead, Moscow went eastwards.

Eastern Expansion: More Furs

We’re now well on our way to explain why Moscow reached the Pacific Ocean before the Baltic or Black Seas: more of the same.

Once all the northern hinterland was secured, Moscow had the farming from its region and the income from the northern trade. It was now ready to fund its line of defense to stop the attacks from steppe hordes. But in the 1500s and 1600s, it was not able yet to control the steppes. It would take centuries for Russia to achieve this.

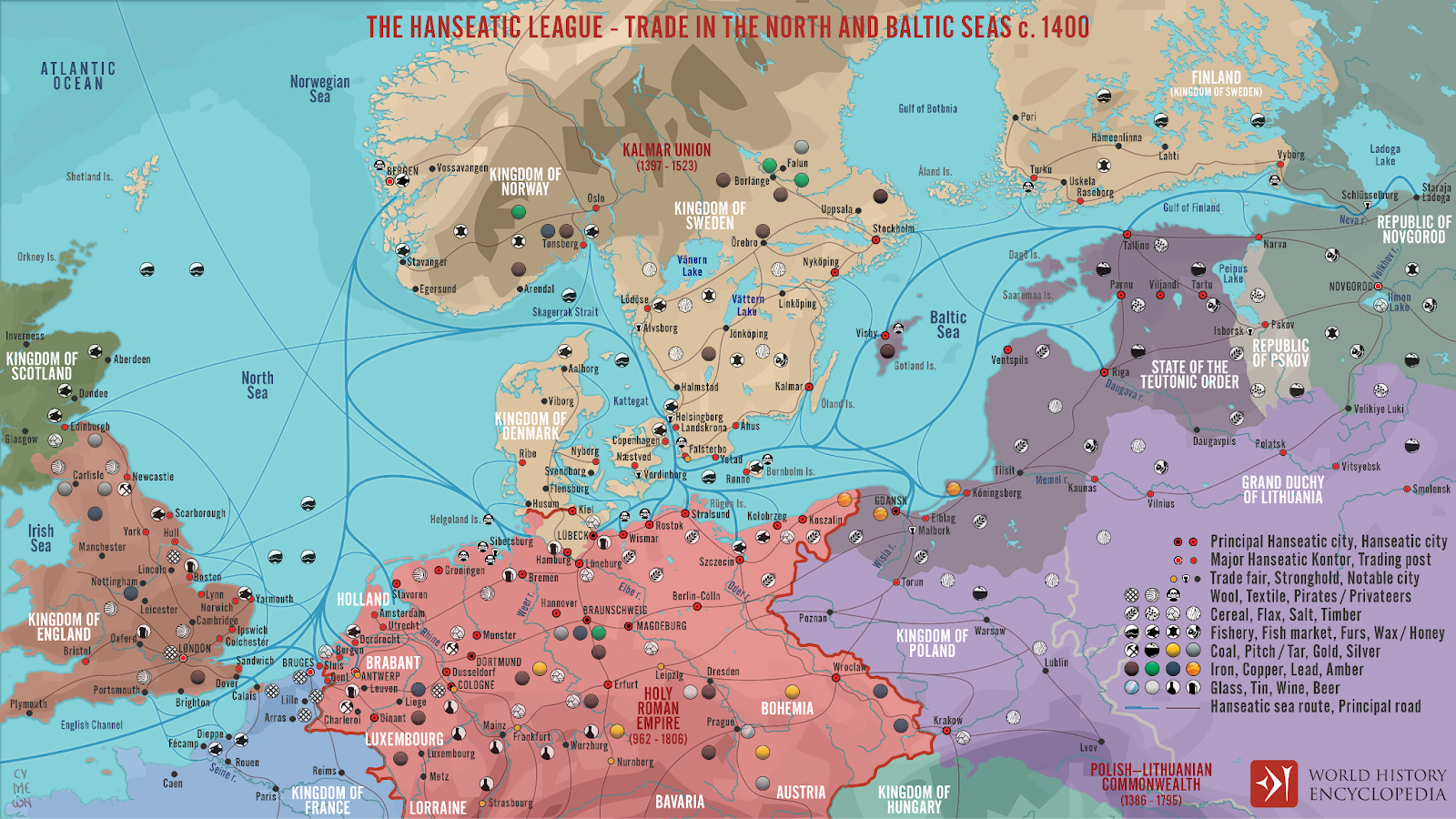

Moscow was also not in a position to challenge much more powerful European countries to its west, including all the Hanseatic League cities. So Russia expanded in the easiest direction left: eastwards. There, it didn’t need to create any new economic model. It has just to expand the one it knew from the north: fur trade.

It took less than one century to conquer everything from the Urals to the Pacific. Why?

We saw it in Russia’s Dilemma: Siberia is too inhospitable.

It’s too cold, too far away from the warming influence of the Gulf Stream

It has taiga forests to the north (and tundra beyond that) and steppe to the south, with only a small stripe that could be used for agriculture.

It’s too far from trade routes, because it has no rivers that flow into trade seas. In Siberia, they all flow into the Arctic Ocean.

No trade means no wealth. No wealth means it was very hard to finance the infrastructure needed to drain the ground and irrigate the fields.

So the region was barely farmed, sparsely populated, and the locals were also predominantly nomads, but much less powerful than those farther south.

Given this poverty, it was easier for Russians to conquer these peoples than the southern hordes.

Add to that the fact that Russians brought diseases with them (like Spaniards to Americans), which killed up to 80% of locals, and you can understand why the Siberian population was not more than 300k people in the 1600s, when Russia conquered them.

So this is why Moscow couldn’t be located farther east:

It controls the Volga River Basin, which is the easternmost river that flows southwards in Eurasia.

East of it, there are the Urals, a huge barrier that made everything east of it poor, as it was disconnected from European markets.

Past the Urals, it was too inhospitable for a large population center to appear.

Why isn’t Moscow farther west, though?

Western Competition

Given everything I’ve told you, it’s obvious that Russia had to be a land-based kingdom. It had to expand across the northern forests, across Siberia, and more importantly, fight the southern hordes. This means all investments went to a land army, so it could afford no strong navy. Hence, Russia had to stay away from the Baltic and Black Seas for the longest times.

It’s telling that, historically, the most Russian city on the Baltic was Novgorod, connected to Baltic trade, yet not exposed enough on the Baltic to get conquered by Baltic powers.

There are also many rivers that flow into these seas, facilitating trade and the kingdoms that emerged from there.

Two examples that illustrate the challenges of powers west of Moscow are the Kievan Rus we discussed before, and Poland-Lithuania, a huge kingdom that marched to Moscow several times.

Technically, Moscow can reach all the way to Germany, where the Northern European Plain shrinks so much that it would be hard for Russia to stretch any further. That means the region between the Oder River and the Volga River was going to be highly contested. At its farthest expanse, the USSR did reach into Germany, but that was untenable given all the advanced societies that emerged in Eastern Europe thanks to its rivers and seas.

So Why Is Moscow Where It Is?

To its north, it’s too cold for farming, so no big city could emerge to prevail in the region.

To its south, nomads “harvested” farmers for centuries, emptying the country.

Moscow is in a narrow band between north and south where it’s ideal: South enough that it can farm, north enough that it has woods to protect it and provide wood.

Given the logistics of the hordes, driven by the southern pastures, seasons, and the Rasputitsa, Moscow was just out of reach from steppe hordes, provided that it could defend itself.

For that defense, it also needed rivers, and the only seriously big east-west river in the area is the Volga and its tributaries. Moscow has a double defense there, thanks to the Oka – Ugra and the Moskva.

The Volga reaches into the Urals, protecting from southern hordes there too.

The Volga also reaches very close to the Baltic, so Moscow could expand northwards easily and take control of the Baltic fur trade.

The city that would control the Volga’s water basin would also control Siberia and its furs, because it’s an empty desert that happens to reach all the way to the Pacific.

To the west, you have too much competition from populations that grew around very viable river basins.

Now we can answer the rest of the questions from the intro:

Why aren’t the Baltic cities of St Petersburg or Novgorod the capitals of Russia? Novgorod was richer earlier on thanks to Baltic trade, and St Petersburg is recent but was for some time the capital of Russia. But although rich, both are too exposed to Baltic powers, and are too far north to develop a big local population from farming.

Why isn’t Novosibirsk the capital, much more centrally located? Or any Siberian city, for that matter? Because historically these were very isolated, exposed to hordes, poor, and backwards.

Why isn’t it Kiev? Because it was in the steppes, so too threatened by the hordes.

Why isn’t the capital somewhere else on the Volga river basin? Why on a secondary tributary? Because most of the Volga river Basin is either too far south and exposed to hordes, too far north and too cold, or too far east to interact with European trade and wealth.

Why did it reach the Pacific before the Baltic or the Black Sea? Because Russia had to be a land army, and there was little competition all the way to the Pacific (but a lucrative fur trade), whereas Baltic and Black Seas had massive competition from seaborn kingdoms and empires.

As you can see, the history of Moscow is the history of Russia. Once it became the capital of a transcontinental empire, people from all over the empire moved to the capital to be closer to its power and wealth.

What does all this tell us about the future of Russia?

Moscow is very much embedded in the North European Plain and its system of trade and communications. It pulls it in that direction. Alternative sources of power will always exist closer to Europe, as long as trade flows.

Its granaries are south and west of it though. They are likely to continue having the highest population densities in the country.

Until some sort of trade-based peace is brokered across the Northern European Plain, Moscow’s thousand years of conflicts in the region will make it insecure and fuel conflict.

Siberia is still foreign land. It’s too big, and Moscow is too remote.

But this leaves many questions:

Beijing is much closer to Siberia than Moscow. Will China challenge Russia’s presence in Siberia? When?

Why does Mongolia exist, if nomads have been suppressed by Russia and China after centuries of invasions?

How did trade work in Russia, with so much cold and so few roads for so long?

How could Russia beat nomads so fast in its expansion eastwards in Siberia, whereas it was having trouble near the Black Sea?

Moscow had another big asset: It gained an Orthodox Church seat a full 150 before it could face the nomads or conquer Novgorod. How come?

These are some of the things we’re going to explore in next week’s premium article.

The Moskva ends in the Oka, which is a tributary of the Volga, which feeds the Caspian Sea, which is only called a sea because the Greek called it so, because they didn’t navigate far enough to realize it’s just a lake.

Canada, the second largest, is a full 40% smaller!

The name of Moscow itself comes from roots that likely mean “wet”, “puddle”, “pool”, “immersed”, or “drowned”.

After Kazakhstan’s Astana and Mongolia’s Ulaanbaatar

Stockholm’s metro area has 2.5M people.

Although it’s a risky proposition to rely on imports for the capital, most northern capitals have direct access to the ocean: Finland’s Helsinki, Sweden’s Stockholm, Norway’s Oslo, Iceland’s Reykjavik, Ireland’s Dublin, UK’s London, Scotland’s Edinburgh, Wales’ Cardiff, Estonia’s Tallinn, Latvia’s Riga, Denmark’s Copenhagen… Canada’s Ottawa, which is farther south than Paris, is on the massive St Lawrence River Valley, and has direct access to the ocean. And yet it’s minuscule compared to Moscow. The only exception I can see is Lithuania’s Vilnius, but the country is much smaller than Russia, and Vilnius is farther south than Moscow.

Steppe warriors were subdivided into units of 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 — in Mongolian, these units were called arban, jaghun, minquan, and tümen (pl. tümet). Source.

The paper has a bunch of references to support each statement.

Kievan Rus is a term from later Russia.

From Andrea Matranga’s thread on the origin of serfdom in Russia: Say you want to feed 10,000 men. Right after harvest the average farm household will have enough food for about 1800 people for a day (365*5 adult equivalents people). So as long as the army finds 6 new farmsteads each day, the General can keep his men fed. This could mean buying 10% of the harvest from 60 farmsteads, or paying them to give you over everything and move to the city. Or if they weren't your people just loot the whole thing.

But if there's no farmers anywhere, you just can't march there for any length of time. An ox team will eat the whole cartload of oats in just 15 days, so in practice any place more than 150km or so from farmers might as well be on the moon (except for water transport!).

They said “in the 1560s”, but I think they meant until then? Wikipedia suggests that’s the case.

Excellent article.

Even many historians neglect the powerful influence that the Central Asian herding societies had on the development of Eurasian agrarian societies. Their existential military threat forced Russia, China and others to grow big and centralized.

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/herding-societies

One point that I would add is that the highly productive soil of modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia could not be plowed before the invention of the steel plow. This made dense populations centers almost impossible to evolve in the Temperate Forest biome. This gave the Herding societies free rein over the region. The invention of the steel plow opened up some of the world’s most productive agricultural regions, including the American Great Plains, the Russian/Ukranian steppe, and the Argentine Pampas.

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/biomes-have-profoundly-shaped-human

I would also add that the rapid development of firearms and cannon tipped the military balance between Russia and the horse archers of the steppe.

A comprehensive overview of why Moscow ended up as the capital. Great explanation of the details that finally come together to allow me to make sense of it.

The Mongols, who created the greatest land mass of territory EVER on earth, were able to conquer not just the Kievan Rus and other major Rus tribes, but also a substantial portion of current day China. It is interesting (perhaps sad) how they have been marginalized in current day Russia.

Power is fleeting. There is never a guarantee that the future will be anything we recognize.

Excellent work, Tomas! Thank you!