The Four Layers of Fashion

Why We Dress the Way We Dress

Who is right?

Derek Guy (@dieworkwear) has built an impressive following thanks to his hot takes on fashion, like this one:

Or this one:

But many people disagree with him:

Sometimes, the disagreement gets heated:

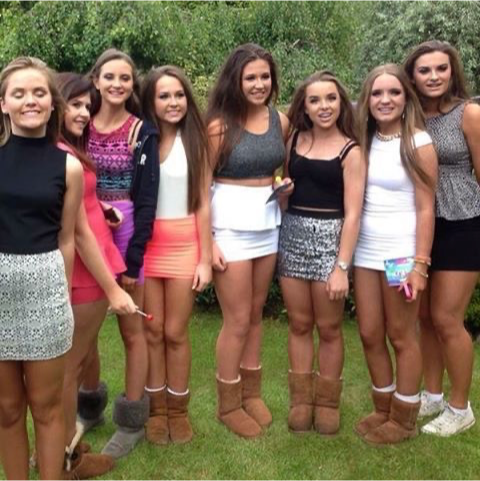

There are thousands of rules for choosing our attire. Which ones are true, and which are just preferences? Are there some universal rules that can explain it all? If so, how do we end up with this type of clothing diversity?

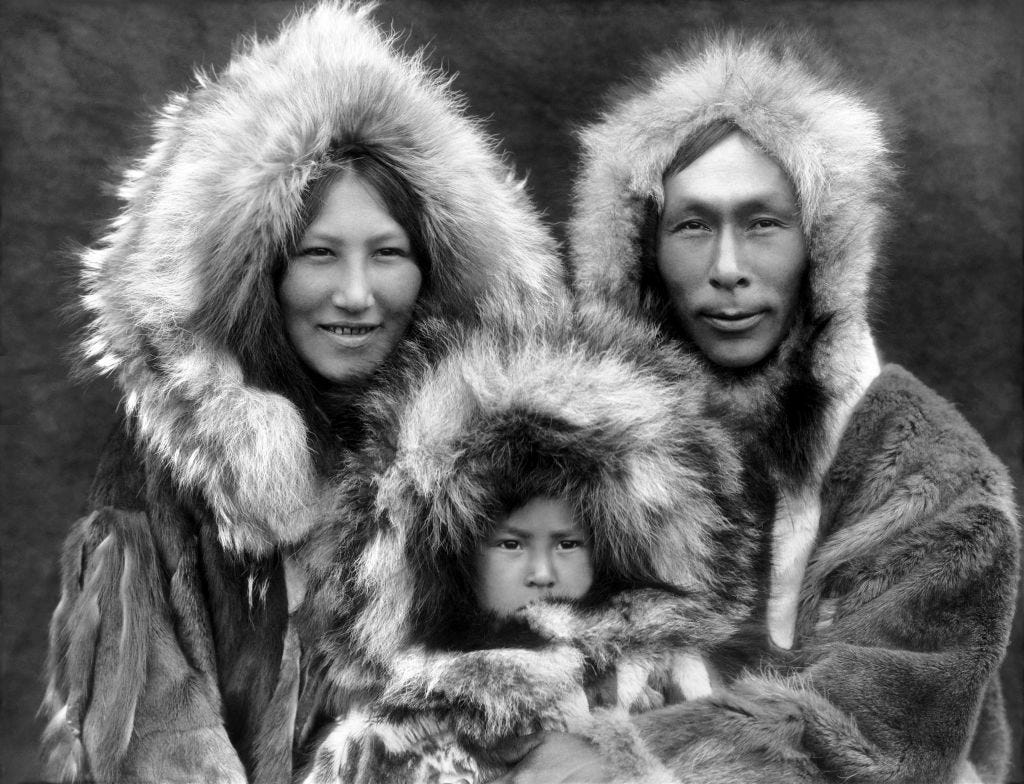

Conversely, did these guys coordinate on a uniform or what?

Why so many jeans?

Why are some outfits in fashion shows unwearable?

How do so many communities end up with very narrow clothing options, within which some specific variations are acceptable?

Many have explored this, like Scott Alexander in Friendly And Hostile Analogies For Taste, but I haven’t found a definitive article that addresses why we wear what we do, so here it is.

Here’s my take: There are four forces that drive fashion:

Function

Aesthetics

Signaling

Path dependency

I think they can explain virtually everything people have ever worn. Here they are, in detail.

1. Function

People use their clothes for raw functional needs like regulating their body temperature, protecting their skin from sunlight, air, or insects, waterproofing, maintaining hygiene…

Vietnamese nón lá hats are wide enough to protect the face from sunlight around the clock, and conical to function as an umbrella.

The West African Boubou is loose and flowing to promote airflow in hot African climates.

Many cultures across the world invented platformed, wooden clogs, ideal to keep the feet dry in wet and muddy terrain.

And so on and so forth.

Sometimes, we don’t realize the function of clothing. For example, everybody used to wear a hat, but we don’t anymore. Is that because fashion or culture simply changed, as suggested in this episode of Freakonomics?

Of course, that’s not the case. Today, we can be fully protected from the environment, going from enclosed homes to enclosed offices through enclosed cars or mass transit. But we used to spend much more time outside, exposed to sunlight, wind, rain, snow…

Now, for the little exposure we have to the sun, we have sunglasses and sunscreen. The sweatband of a hat could catch beads of perspiration before they got into your eyes, but now we don’t perspire as much, and when we do, we can easily shower.

Meanwhile, hoodies and vests are famously associated with Silicon Valley.

Why? My guess is that it’s a specific result of the weather in Silicon Valley, which doesn’t change that much throughout the year, and is warm during the day and cold at night. As a result, everybody must follow the onion strategy: Wear many layers of clothing so you can take them on and off depending on the moment of the day or whether you’re outside or inside. The hoodie is perfect because you can open the zipper if it’s too hot, or put the hood on if it’s too cold. Similarly, the fleece allows you to warm up a little bit but not too much, and is easy to put on or take off. Both these items are not cumbersome, so they allow you to work on a computer all day long. Additionally, Silicon Valley is a highly meritocratic place where performance can easily be assessed, so status markers are not needed on clothing.

2. Aesthetic

Beyond functionality, some garments are just more beautiful than others. Sometimes, that’s obvious:

These things don’t work well together, but why exactly? There are a few rules:

Vertical Lines

We like tall people for evolutionary reasons: It’s a sign of healthy food access while growing up and of physical strength, both signals of leadership. Maybe that’s the reason why we find elongated figures more elegant. For that, it’s best if there are not too many cuts to the vertical lines of a body. Unfortunately, here we can see the shoes, the socks, the leg, the shorts, the t-shirt, the neck, a cap… Each layer has a different color, cutting vertical lines too much.

Contrast

If many pieces of clothing contrast too much, the eye doesn’t know where to go. There is no coherence to the outfit. Compare those with Spain’s King Felipe VI: Broadly the same color for his entire outfit.

There is very little contrast, but the existing one is well used:

Hands must be free anyway, and contrast with the suit. Showing a bit of the sleeves of the shirt there is thus not jarring.

The collar and the tie open up the suit from a narrow point, pushing the eye up towards the wider opening that ends in the face. This shape actually encourages us to look at people’s face, which is desirable.

This is also the reason why Steve Jobs wore black turtlenecks and jeans

The eye barely registers the pants and shirt, which enables the hands and face to stand out.

Color

Obviously, color matters a lot. Red attracts our attention because it’s the color of blood, so we evolved to pay attention to it. Yellow reminds us of the warmth of sunlit afternoons, green for the tranquillity of plants, etc. Complementary colors stand out the most, so people combine them to highlight things.

This is why so many movie posters are orange and blue:

There are a million more color rules; this is just a sample.

Proportions

You’ve probably seen this image of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man:

It makes the claim that many human proportions follow the golden ratio1. It isn’t really true, but the point stands that many human proportions are close to that ratio: the ratio of the torso to the leg is similar to that of the leg to the entire body, and to the upper leg vs the lower leg, and the lower leg vs the full leg, and the arm to the leg, and the upper arm to the lower arm, and…

Since this type of ratio is common in human anatomy in particular and biology in general, it’s useful for good proportions, which is used consistently in fashion under the rule of thirds.2

Shapes

We started discussing shapes with Felipe VI, but there’s of course much more to it. One example is that the V-shape of the male body conveys upper-body strength, and is thus preferred. Hence the use of shoulder pads in suits, for example.

In the past, we’ve discussed how the female waist-to-hip ratio is a strong signal of fertility, so crop tops and low-waist pants that show them off are aesthetically pleasing.

Another example I gave recently is how heels are probably aesthetically pleasant because they increase the angle between the back and the buttocks.

Symmetry

Humans prefer symmetry, because usually people who have grown up healthy have more symmetrical faces than those who haven’t. This then applies to garments: As a rule of thumb, most of them are symmetric, including shirts, pants, shoes, earrings… Asymmetries can be aesthetic, but not as a rule: Too much asymmetry will just look off. Asymmetry grabs the eye, so a little asymmetric detail will be the touch that is aesthetic.

There are probably hundreds of other rules. Some you might know, others you don’t, but they exist and have a rational reason behind them. Once you know them, you can apply them.

For example, why are Crocs so unfashionable?

They were designed only for comfort (function) and the tradeoffs have been really bad for aesthetics:

They have bright colors, which break the line of the leg.

They don’t espouse the natural shape of feet, with a big blob at the tip.

They’re made of plastic, which causes the foot to sweat, which smells poorly.

So they have holes to allow them to breathe, which again form a completely unnatural shape, as feet don’t have big dark circles at the top.

But that’s not enough to avoid the sweating and smell, so some people put socks on when they wear them, which further breaks the line of the leg.

Compare Crocs to flip-flops: The foot breathes more so it sweats less and smells less, they let the natural shape of the foot shine (it’s the actual foot!), don’t cut the leg line…

Here’s another example: Aren’t white socks a fashion faux pas? Then why did Michael Jackson wear them?

Didn’t we just say we are supposed to lengthen the line of the body with a single color? Don’t these white socks break the line?

Yeah but that’s the point here, because Michael Jackson wants us to pay attention to his feet! He contrasts the black of his pants and shoes and stage with the white of the socks so we really really see his legs when he is doing the moonwalk:

Or course, that’s also why at some point he added a vertical line to his trousers—to highlight the movement of his legs. And why the rest remained black—to keep the contrast as high as possible. It was all intentional, but he could only break the rules because he knew the rules.

Most people don’t know these fundamental aesthetic rules, so they follow them blindly without understanding their rationale. This means the rules appear arbitrary and people don’t know when they can break them.

3. Signaling

The third driver of fashion is signaling. Fashion is a great way to communicate with others because everybody sees it instantly and understands it without even thinking. Arguably, it’s the fastest way to communicate lots of information in person, and people have taken advantage of that since forever.

There are many things we can signal with clothing.

Status

The main one is status. People want to convey that they are at the top of the hierarchy. The most obvious way is through money: If you can burn lots of cash on your clothes, odds are you have more money where it came from. The entire luxury industry is based on this simple insight.

There are other ways. In antiquity, the color purple was very hard to produce: Only Phoenicians were able to produce it, and it required the painstaking work of collecting thousands of sea snails. Roman emperors kept it for themselves, so only they could wear Tyrian purple capes, and other eminent people could line their garments with it.

Yet another example is corsets.

They had an aesthetic function: To highlight a low waist-to-hip ratio. But they also had a signaling function: You couldn’t do manual labor while wearing this, so it would show you had enough money to not work with your hands.

A very common way of signaling status with clothing in the past was through the type of cloth used. Silk, for example, was so scarce for thousands of years that wearing it immediately signaled wealth.

Authority

Of course, a variant of status is authority. This is typical in uniforms.

They tend to have some functional aspect, like military camouflage to hide from enemies, or green scrubs to avoid optical effects from blood. But many aspects are decorative, just to convey the idea that this is a uniform, so you should respect the wearer accordingly.

Belonging

Remember the Silicon Valley hoodies? They might have started functional, but they became a statement, like when Mark Zuckerberg wore a hoodie to Congress.

He was telling politicians: I come from another center of power, and I don’t bow to yours.

Indeed, sometimes clothing signals belonging to a group, not for the sake of the authority, but simply for the belonging: school uniforms, saffron robes for Buddhists, hijab for Muslim women, university clothing, goths, sports team members, traditional dress, branded hoodies for Silicon Valley companies…

Sometimes, belonging to a group that flaunts authority will pick something purposefully ugly. I believe this is one of the reasons why teenagers wear Crocs: They’re comfortable, so there’s plausible deniability that they wear them for that, but another component is to wear something that is considered ugly by adults: See? I don’t follow your rules. And since they’re truly ugly, kids can also signal that they’re willing to stand a public cost (ugliness) to belong to the group of cool kids—a bit like a Yakuza could cut a finger to show they belong.

Some are much more subtle, like wearing brand new sneakers like the cool kids.

Suits look good, but they are also a convention we landed on to show respect: I make the effort to don a suit to show you that I abide to the codes of what is proper attire.

Some of these are probably even subconscious. When you buy jeans, you might not realize that part of it is because it’s accepted as the standard for trousers everywhere. As long as you don’t need casual attire, you know you’ll fit in anywhere.

Individuality

But we don’t want to just blindly belong because then we are sheep. Within the boundaries of what’s acceptable by the group, we must show our individualism. We might wear jeans, but the specific cut we choose, or the specific color, or the tops we combine them with, or the jewelry or sock and tie color… All these have an aesthetic aspect, but also one of simply being different and unique.

Sexuality

We touched on how some aesthetic aspects of clothing can convey sexuality, like showing the waist in women or the V-shape in men. But clothing can convey other aspects of sexuality, like chastity. This is the point of much Muslim dress code for women: They’re hidden to avoid the male stare (functional), but wearing it also conveys the messages that they belong to the group and are modest.

To me, demonstrating sexuality is the reason why Jeff Bezos dresses like this:

He is conveying that he is a normal guy with his jeans and polo, but he’s also showing muscle, which conveys strength and the capability for violence—attractive to many women.

Fads

When you are wearing the latest trendy garment, cut, color texture… you are signaling 2 things:

I can spend enough time analyzing clothing trends, which signals that I have lots of time to burn (therefore I’m not slaving away for cash) and I’m intelligent, because I can discern what is fashionable and what is not.

I can afford to buy clothes that are trendy right now, and change them constantly, along with the trends, which signals wealth.

The faster you catch a trend, the cooler you are. You belong to the inner circle. If you catch the trend one year later, though, you’re seen as someone who doesn’t belong to the in-crowd: You’re trying too hard and yet are too late.

4. Path Dependency

The last rule is that all the rules above create a history that determines the fashion of the centuries that follow. Old social structures, class systems, materials, functions, fads… they accumulate over time and evolve, but vestiges often remain.

For example, we wear jeans because gold miners and cowboys wore and popularized them, even if most of us don’t mine or herd cows anymore. We wear ties because Croatians used colorful pieces of cloth to tie the neck of their jackets, and the French king Louis XIII started wearing them too, devoid of their original functionality. Present-day ties are just the descendant of that.

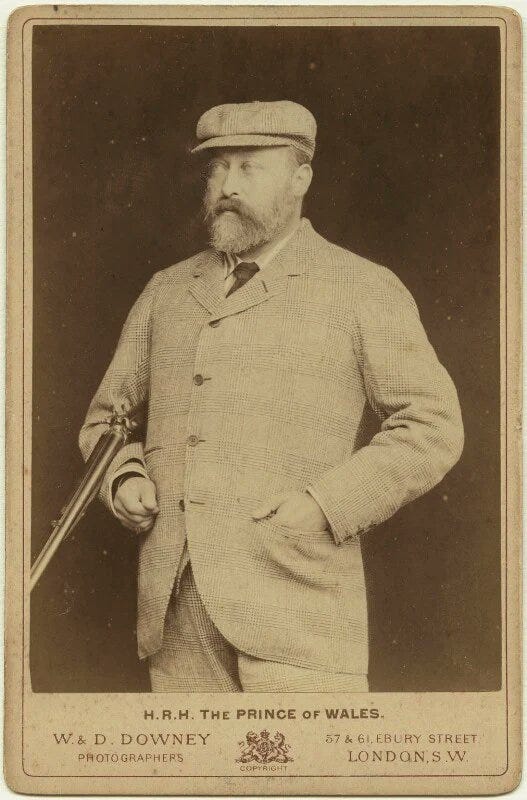

Why do suit lapels have buttonholes, but only on the left?

They are useless now, but as Derek Guy explains, they used to have a function. Originally, jackets were designed to close at the neck.

But then some people started reverting the collar when they were not closing it.

Eventually, we stopped closing the jackets altogether, the right lapel lost the button, and standard suit lapels came to be, but for some reason the buttonhole to the left remained.

Here’s another example from the same source. This is a Type III trucker jacket. Look at the v-shapes on both sides:

Type III derives its history from the Type I and II jackets, which feature pleats that run parallel to the placket.—Derek Guy

These pleats could be released to make the jacket looser—useful at a time when fabric was precious and ppl wore clothes for decades. When companies came up with their modern version of the trucker jacket, they included a similar detail as a nod to the garment's history.—Derek Guy

We talked about inuit ruffs earlier on. Of course, now we get this:

Is this ruff made of wolf fur so that it can create turbulence in ice cold wind and keep moisture while not freezing with it? No. It’s faux fur made of plastic that probably keeps no moisture and freezes hard. It just reminds you of those older coats, so it gives you a feeling of coziness and warmth.

Takeaways

So we have four forces:

Function

Aesthetic

Signaling

Path dependency

They combine to create impossibly complex rules that are hard to parse, but exist nonetheless, and drive fashion through history. This now allows us to answer our questions from the introduction:

Why are there so many types of garments? Because these rules are very complex and their combination creates infinite possibilities.

Why are there places and times in history where the general fashion was the same for everybody, with only a few differences? Because these places had a specific climate that requires a certain type of garment, those making them specialized in one instance type, and the community would want to keep the “uniform” to show belonging, yet want some differentiation to mark status and individuality.

Why does the fashion guy on the Internet disagree so much about showing muscle in outfits?

In his threads, Derek tends to complain about things like the fact that the polo has no history (path dependency), that it’s shapeless (aesthetics), that this last outfit doesn’t follow the rule of thirds (aesthetics again)... What I think he misses, however, is that a big strong body is now a standout status marker: It’s very difficult to develop this type of body: It takes hours at the gym every day for years on end, so it can’t be faked with money. This is at a time when displays of wealth are both disparaged and unnecessary, as many people know who the richest people are. The result is that men want to use their strong body shape as a status marker, and are willing to go the extra mile to show it. If it is at the expense of wearing clothes that are too tight, it’s worth it for them.

Derek emphasizes aesthetics and path dependency, while these other people focus on force status signaling.

Why do fashion shows feature impossible clothes? Because these garments are not designed to be worn, so function, aesthetics, and some signaling such as belonging don’t matter as much. Their role is to spread virally by creating an image of exclusivity and creativity. This adds to the image of the brand, which can then design more wearable clothes and piggyback on those associations.

What do you think? Are these rules truly enough to explain all fashion? Did I miss any?

And if you are not fully convinced, that’s what the premium article of this week is going to be about: I take a few examples of our most cherished types of garments and show how much these rules have determined them. Subscribe to receive them!

a/b = b/(a+b)

The inverse of the golden ratio (~1/1.618) is ~0.62, which is close to two thirds (0.67).

Fashion has always perplexed me, this was helpful.

The golfer I believe is Arnold Palmer, not Daniel Craig.

Though an article on James Bond clothing would be intriguing!

Best essay ever, Mr. Pueyo - loved it.