A Brief History of Spain

Why did Spain, and not another country, conquer most of America?

Why have so many Spanish regions pushed for independence in contemporary Spain, like Catalonia or the Basque Country?

Why are Spain and Portugal not united?

In Spain, what is the legacy of Muslims, who ruled the region for 800 years?

Why is it a secondary power in Europe now, despite having been the most powerful country in Europe for centuries?

What are Spain’s strengths, and what can it do in the 21st century to play the hand it's been dealt to its best advantage?

All of these questions revolve around Spain’s conundrum: On one hand, it created one of the biggest empires the world has ever known. Today, however, it’s only the 6th economy in Europe, breaking at its seams with separatist movements like those in Catalonia and the Basque Country, and weirdly sharing the Iberian peninsula with its smaller neighbor Portugal. How could such a fractured country give rise to one of the most powerful empires ever?

It all starts—you guessed it—with geography.

The Iberian Chessboard

This is the Iberian Peninsula.

If you have been following my articles, you should be able to look at this map and start predicting where wealth, people, and countries would emerge. So go on, have a good look before I tell you.

OK, the first thing to note: SO. MANY. MOUNTAINS!

And by now you know this comes from the European and African tectonic plates colliding.

Mountains, as you know, mean fewer people (because agriculture isn’t viable) and less wealth (because trade is much more expensive, so less viable). But the Iberian Peninsula has a handful of valuable land areas1.

This defines most of the features of Spain’s population:

Densely populated coastal areas wherever land is somewhat flat (blue on the map).

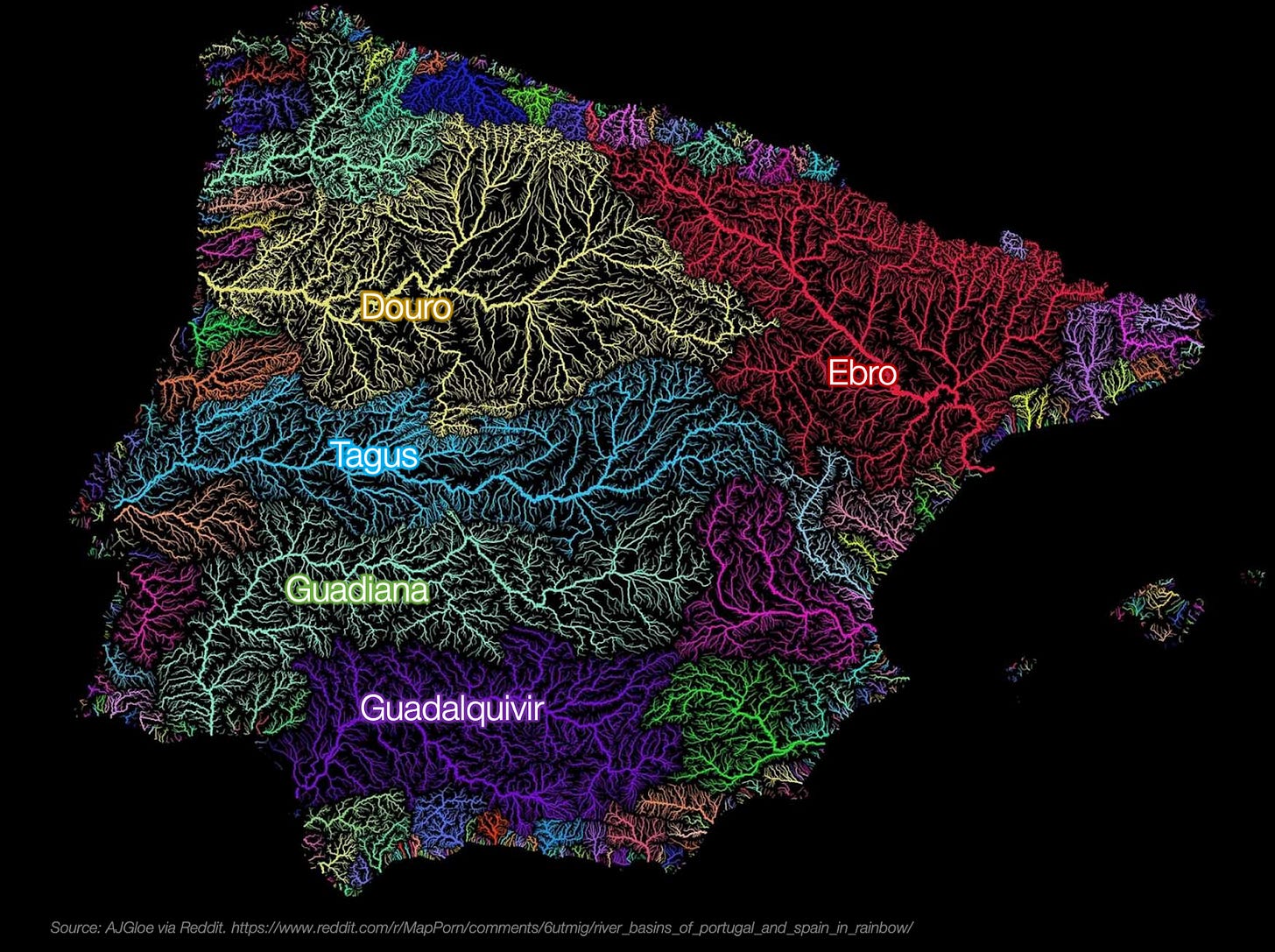

Two river valleys in the Ebro and Guadalquivir (green), also heavily populated.

Some central plateaus where agriculture can take place (yellow), with less population.

First, the coastal areas. They are small but fertile, and give ready access to the sea. This is why some of them were the first to enter written history: Those on the Mediterranean coast first flourished as Western outposts of early Mediterranean civilizations—Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks.

Second, there are dozens of rivers in the peninsula, but only five major ones.

But with all these mountains, even these rivers are barely navigable. The Tagus and Douro rivers have about 100km of navigable sections in Portugal. In Spain, the Ebro can be navigated in some areas, but not all the way to the Mediterranean. Only the Guadalquivir in the south could be navigated historically to a similar degree as the principal rivers in France.

Third, the plateaus are not very populated: Not only do they have few navigable rivers, on top of that, these regions are all quite dry due to the rain-shadow effect.

From Geography Is the Chessboard of History: Bonus Content:

Because nearly all the Spanish coast is surrounded by mountains, when clouds arrive, they drop all the water before they make it to the interior. This is called Rain Shadow: As wind full of moisture arrives on land, it goes up, pushed by the mountains. There, the air is cooler, so the water condenses, and it rains. The dry winds proceed to pass the mountains, and once on the other side, there’s no water left.

And since winds come mostly from the Atlantic, you end up with a very wet Atlantic coast for Spain and Portugal, but dry regions nearly everywhere else.

This is especially true in the northern coast vs the center. The mountain range that spans the entire Iberian peninsula from Galicia in the west to Catalonia in the east has different names (Cantabrian Mountains in the west against the ocean, Pyrenees against France), but it’s the biggest barrier for both humans and clouds.

The following pictures were taken within 10 km of each other, one on each side of the Cantabrian Mountains:

The following picture one was taken about five minutes later, after going through a couple of tunnels:

This is south of the mountains. As you can see, it’s dramatically drier than in the north, with fewer trees, more bushes, and fewer clouds.

Mountains, coastal areas, river valleys, and internal plateaus are the reasons why people and wealth are where they are today in Spain:

Most of the wealth is in the coastal areas. Then you have the valleys of the Ebro and Guadalquivir. And finally there are a few cities here and there on the plateaus, with Madrid the big one in the center.

You look at this map and wonder: Damn, this should be like a dozen countries!

As in the Balkans, or the Caucasus, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Central America, when you have so many mountains separating people, they grow apart. They develop their own culture. They fight each other. They want independence. Even the most stable mountain regions, like Switzerland, are extremely federal.

If, on top of that, the mountains separate several reasonably good regions, these will tend to develop independently and avoid relinquishing their power to their economic rivals.

So why didn’t that happen here?

It did, but for a weird accident of geography and history, a more powerful force overrode this centrifugal force.

One Small Region of Indomitable Locals

This is how long it took Romans to conquer all of the Iberian Peninsula:

It took Romans eight years to conquer Gaul (most of what is France today), but over 200 to conquer Hispania. They started before and finished later. At the time, there was no advanced civilization to fight in Hispania, and yet the very advanced and bellicose Romans still couldn’t manage to beat the natives quickly. Now you know why: Those damn mountains.

Co-opting the Mediterranean coast was easy. Subduing the entire Iberian Peninsula was a nightmare. It took so long and proved so hard that Augustus himself led the last campaign, the Cantabrian Wars, in the northern mountain range, the Cantabrian Mountains. Don’t forget this, we’ll get back to it.

The Iberian Peninsula became the Roman region of Hispania, and developed reasonably peacefully for the next five centuries. The legacy of this time is colossal: the language, the religion, and even the infrastructure, a blueprint that Spain has followed to this day.

When the Roman Empire fell, around 500, overwhelmed by barbarian tribes, some regions were more stable than others. The Franks emerged as the biggest superpower in Europe, forming a new empire across France and Germany (because of the Northern European Plain, as we saw in How to understand France).

And yet the Franks took over 300 years to conquer the Pyrenees. At the height of that empire, under Charlemagne2, his invincible forces were beaten twice in the Pyrenees by the Basque.

Parts of the Pyrenees would eventually be conquered, but not for long, and the region that remained part of the empire was instead a loosely-connected buffer against the Muslims, the Hispanic March.

Aside from the Franks, many other Germanic tribes invaded Hispania after the fall of the Romans: Suebi, Vandals, Goths, Visigoths… But union was nearly impossible given the geography. Groups of barbarians fought locals, against each other, and within their own tribes. The next 200 years were just a succession of kings and wars and princes and civil wars.

Eventually, the romanized Visigoths prevailed, but they were so debilitated, that when the Muslims appeared in 711, they conquered the Iberian Peninsula in just seven years.

Muslims were a strong emerging power.

They sent wave after wave of soldiers to conquer everything from Portugal to Afghanistan in a record 130 years. Visigoths couldn’t stop that steamroller.

But mountains could.

Remember those mountains that Romans took forever to conquer? The Cantabrian Mountains? The almighty Franks never even reached it. They had enough of a hard time with the eastern side, the Pyrenees. Muslims, like the Romans or the Franks, could not easily take over that same mountain range. So they avoided the Cantabrian Mountains and kept moving along. They used a pass through the Pyrenees to invade France, but being so far away from their base, cut off by such a huge mountain range, they could not beat the Franks, who pushed them back to the Iberian Peninsula.

So the same mountain range that slowed down Romans—who were a superpower fighting against prehistoric tribes—was too much for Franks or Muslims. The Muslims decided to remain south of the mountains and established themselves in Spain.

The mountain locals created their own kingdoms, like the Kingdom of Asturias in the map above. But at this point, this map suggests it was way more stable than it actually was—as you could expect, since it occupied the Cantabrian Mountains.

All the people from Iberia who wanted to escape from the caliphate went here, in this long and mountainous region, where they met Galicians, Asturians, Cantabrians, Basques… Each one had a different idea of who should be boss.

But they all had one thing in common: their enemy.

Muslims, the Uniters of Spain

The northern mountains might not be very conducive to peace in normal times. But these were not normal times. These peoples were all Christian, and they shared an enemy on the other side of the mountains.

So through alliances, intermarriages, and intermittent civil wars, the mountain Hispanics muddled through their Reconquista against Muslims. It took them 800 years to do it. Here are the first 300:

When the Reconquista is taught in Spain, the narrative is “A group of Christian Spanish kingdoms from the north allied to take on the divided Muslims”. The only part of that narrative that's accurate is the characterization of the Muslims as divided.

Early on, the Muslim rule in Spain was pretty stable. But as you could imagine with such an adverse geography, over time it degraded into Taifas, small independent Muslim kingdoms in the Iberian peninsula3. Divided, they had a much harder time uniting against Christians.

Not that Christians were much better. You had a Kingdom of Asturias, Kingdom of León, Kingdom of Castile, Kingdom of Galicia, Kingdom of Pamplona, Kingdom of Navarre, Kingdom of Aragón, Kingdom of Portugal, Catalan Counties, Kingdom of Viguera…

Christians in the north and Muslims in the south were not very different. Both were just a bunch of kingdoms fighting both the other religion and amongst themselves, which made sense given that Spain is so. damn. mountainous.

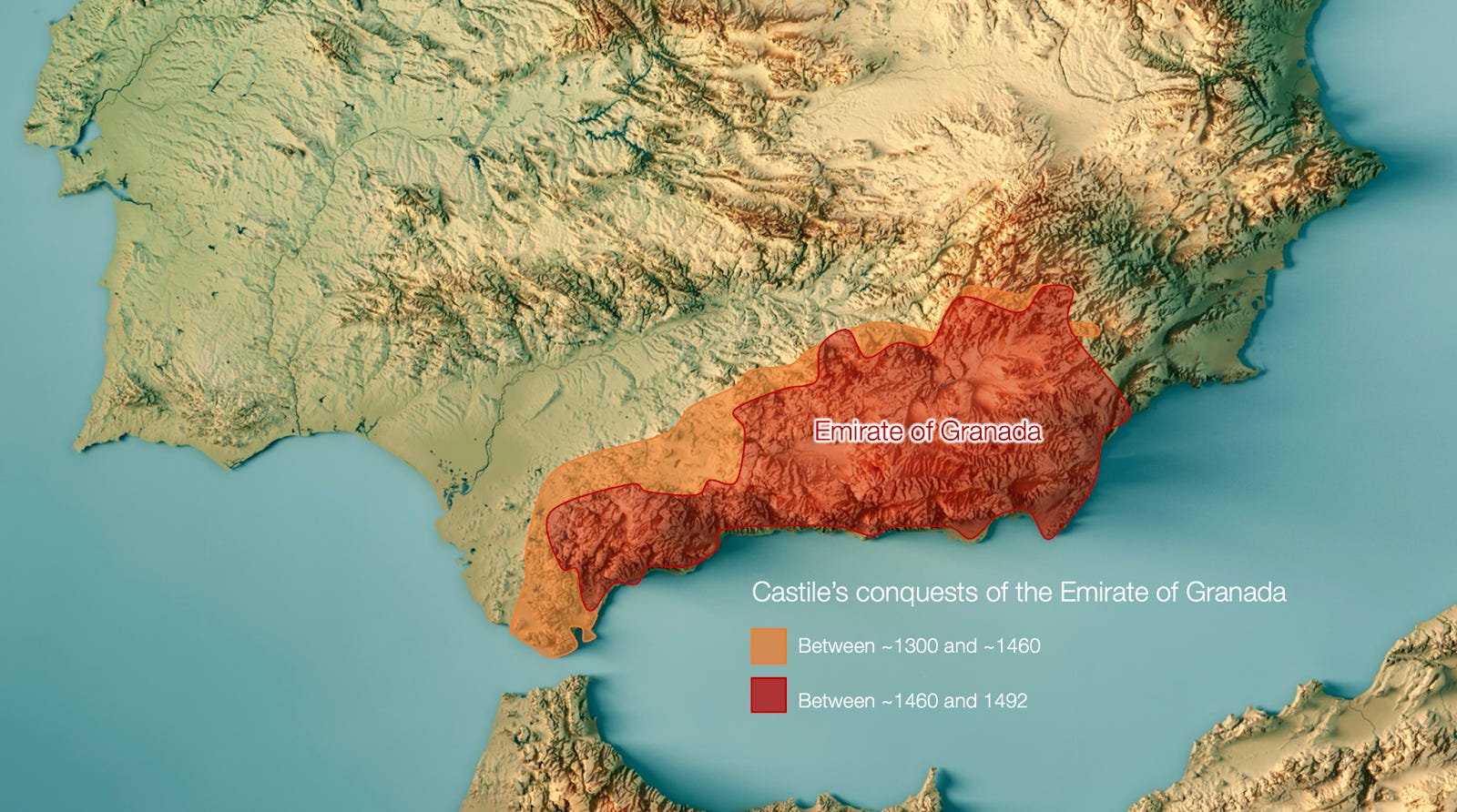

The impact of mountains can be seen all the way to the end of the Reconquista: It took two centuries to conquer the last mountain range.

After 800 years, Christians eventually prevailed. Why?

If you ask the winners—history’s writers—they’ll tell you it’s because of the strength of Christianity (but then why did the Muslims prevail early on?), or the superior military force of the northern kingdoms (but what was special about them?), or something like that. What are more objective reasons?4

Christians in Europe cared more about winning back their lands from the Muslims than the other way around. Remember: this is the period of the Crusades. Spanish kingdoms had help from other Christian forces, for example, from the Knights Templar.

The center of the Muslim strength was in its origin in the Middle East. They had to cross a desert to get to what’s today Morocco, and then the 13km-wide Strait of Gibraltar. The fact that there was so much distance on land, and then some more distance by sea, made the distance vast between the core of the Muslim world and its border. Conversely, in Western Europe there’s lots of mountains, but it’s quite compact and there are some passes through them. Although they’re difficult to attack, it’s easier to cooperate on them than between Northern Africa and Spain. The opposite can be seen in the fact that Northern Africa remained Muslim, and when Christians tried to cross the Mediterranean to regain the Holy Land during the crusades, it was mostly a failure.

It was hard to get to the mountains from the plains, but not vice-versa. So the people from the mountains were defended but could easily attack. This is not true for the Strait of Gibraltar.

Europe is a much more fertile area than the Maghreb, northwestern Africa. So the Christian population growth was probably higher than Muslim growth5.

Christians were better defended through the Northern mountains.

After a phase of Islamic apogee, Christian Europe started developing faster, supporting the Spanish Christian Kingdoms. It took a long time to get out of the Dark Ages, the period of drop in civilization that happened in Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire to the barbarian hordes. But when Europe did, starting around the year 1000, it pushed hard against its neighbors.

Christianity grew in Europe unimpeded by other religions. Most natives were Christians by the time Muslims arrived. There was no religious conflict in Christian areas. Conversely, Islam had to compete with Christianity when it conquered an area. The result was that Christian regions were much more religiously united than the Muslim ones6.

As the incumbent, Muslims focused more on themselves than on the challenger. The challenger is always more focused on winning. This is in fact how Muslims took over the Iberian peninsula in the first place: it was during a civil war between Visigoths, and one side asked the Muslims for help.

As the challengers, Christians had a specific policy that Muslims couldn’t match: the fueros. You could keep all the land you could conquer from Muslims and successfully defend7.

Christians did conquer the Iberian Peninsula, which eventually became two countries: Spain and Portugal. Why not one? Why these two and not others? How that happened would be one of the most momentous accidents in world history. I will cover this in the upcoming articles: A Brief History of Portugal, Why Catalonia Is Part of Spain and Not Portugal, and The Origin and Destiny of Spain’s Languages. In the meantime, let’s follow Spain’s trajectory.

The Spanish Empire

1492

The Reyes Católicos, Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragon, married in 1469. They became respectively Queen of the Crown of Castile and King of the Crown of Aragon in 1479, and were merging their Crowns into one country8 when they conquered the Emirate of Granada in 1492, finalizing the Reconquista.

When you spend 800 years conquering land and you run out of land, what do you do? You take to the boats.

Granada capitulated on January 2nd 1492. That same month, Isabel La Católica summoned Christopher Columbus. In April9, she decided to fund his travels. By August, he was sailing, and by October, he had stumbled upon America.

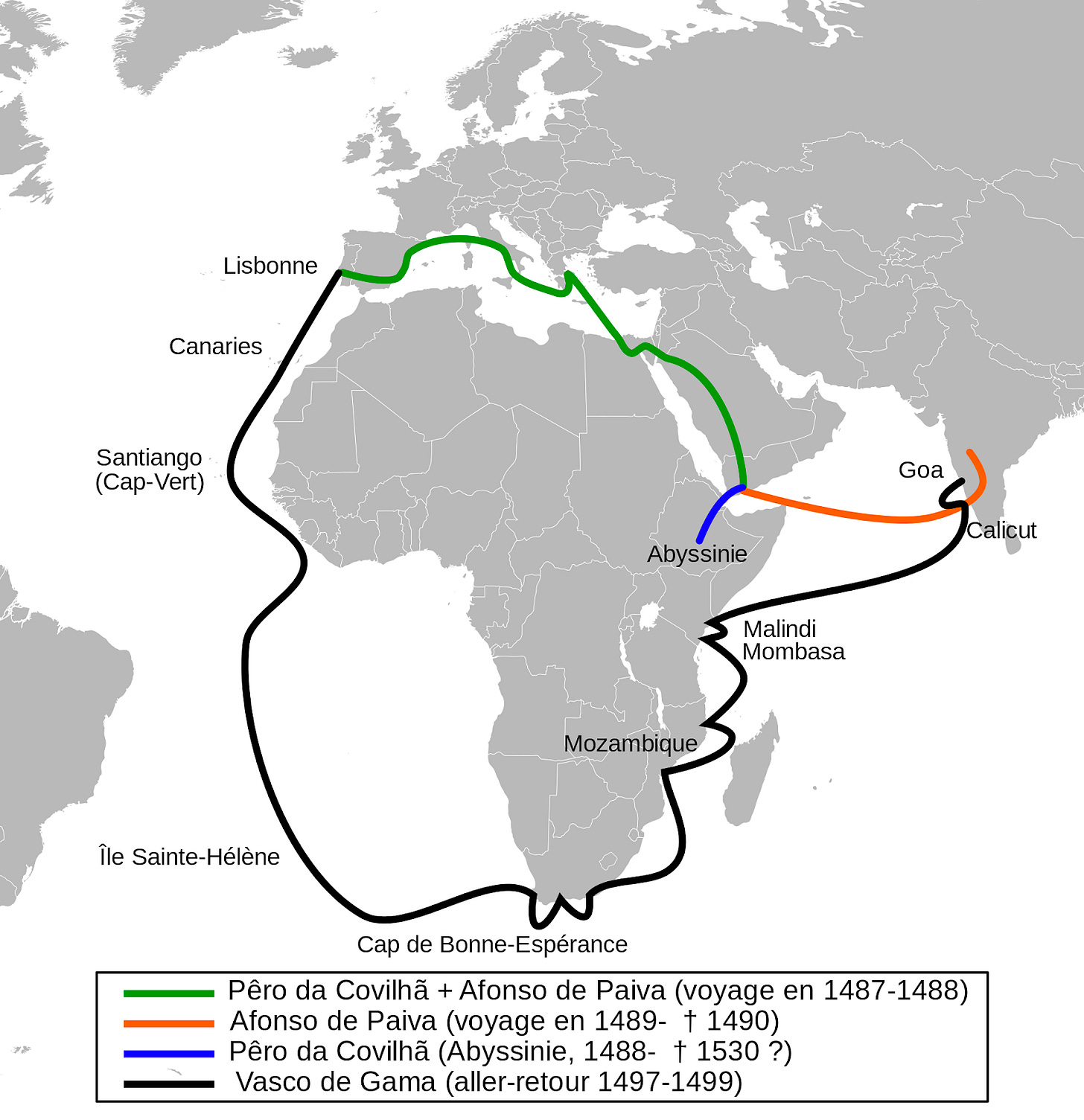

At the time, Spain was looking for a travel route to the Indies: Constantinople had fallen in 1453 to the Ottomans, who forbade Christians from trading in the Silk Road. This meant that the Mediterranean trade was suffering, and with it all of Spain’s possessions in that sea.

Meanwhile, Portugal had just discovered a way to the Indies around the south of Africa.

It was unacceptable to leave Portugal to profit from this new trade route. Spain needed an alternative. This is one of the main reasons why Spain financed Columbus’s trip.

The Age of Discovery

Initially, Spain didn’t realize how momentous the discovery of America was. The kings were mostly disappointed that they hadn’t discovered the Indies, or that there wasn’t much gold to plunder. But eventually, conquistadors discovered the silver of Mexico and Bolivia. Between the money and the moral imperative of spreading Christianity, this was the beginning of Spain’s serious investment in America, and its eventual colonies in the continent.

I go into a lot of detail on these episodes in my two previous articles: A Brief History of the Caribbean, Part I and Part II.

It took 300 years to conquer America, but by the time of the French Revolution, most of it was either Spanish or Portuguese.

But back to the early 1500s. If merging Castile and Aragon, expelling Muslims, and discovering America wasn’t enough, the Catholic Kings Isabel and Fernando had yet another ace up their sleeve.

They married their daughter with the eventual heir of the Holy Roman Empire. Not bad. Their grandson would become King Charles 1st of Spain and 5th of the Holy Roman Empire.

Charles did not keep these two together. When he abdicated, he gave Spain and the Netherlands to his son Philip II of Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire to his brother Fernando I.

Spain conquered the Philippines10 around that time too. Why conquer America, a massive continent that you can’t even manage, and yet try to add some islands on the other side of the world?

Discovering America was good and all, but Spain didn’t care much. They were not originally interested in a land of natives they couldn’t juice. What they wanted was a trade route with the Indies.

So the Spanish kings financed Magellan’s expedition to find the Indies going west, and that’s how he led the first circumnavigation of the world11.

Magellan did find the Philippines, which Spain conquered a few decades later to use as a trading post with Asia—and to convert some locals to Christianity on the side. But the route around the south of America was too long, and Spain eventually settled for a trip from the Philippines to Mexico, across Panama, and from there to Spain.

Soon after, the same king, Philip II, was able to merge Spain with Portugal through his wife.

This was the apogee of Spain—and its undoing.

Overreach

Reaching the summit means you have only one way to go: down. Which means whoever was at the helm at the time did a pretty poor job, and turned a rising star into a sinking ship. Under Philip II, Spain defaulted on its debt five times, the Netherlands became independent, and 40 years after his death, Portugal became independent too. Why was it so disastrous?

Philip II had many goals:

In Europe, he wanted to keep Spain, Portugal, southern Italy, and the Netherlands united, all disconnected territories.

France, Spain’s northern neighbor, was a strong and rising power at the time. He wanted to undermine its power.

An ardent Catholic, he wanted to support Catholicism against the Protestant Reformation.

And against the rising Ottomans.

And spread it to the New World.

And to the Philippines.

In trade, he wanted to settle America and exploit its riches.

But also establish trade with Asia.

All the while excluding other European powers from the possessions it claimed in the New World.

In other words, Philip II lacked a prioritization framework.

He could only hope to achieve all of this by burning through the riches of its territories, which meant Spain was impoverished, the overtaxed Netherlands revolted, America was exploited, and Portugal’s empire was undefended.

One way to think about this is like MBS, Saudi Arabia’s heir: flush with cash from decades of oil extraction, he has grandiose plans to burn it in a 170 km-long building.

Neom, MBS’s plan to burn through $1 trillion.

This is a crazy dream that is most likely impossible, and will burn Saudi money while it’s available. This is what absolute monarchs do when they are dealt an amazing hand: they think they’re the best and can afford any dream, but they’re just squandering money.

Philip II was the same. The Spanish hegemony could never stand the test of time for at least five reasons:

First, with such mountainous land in the Iberian peninsula, there was no way Spain could ever generate enough wealth or population to control vast swaths of Europe.

Spain was a big country that was able to unite because of an accident of history, as we have seen, which made its population nearly as large as any in Europe.

But despite its size, Spain’s geography remained far more challenging than that of its neighbors, which meant the country was always going to be poorer per person.

Second, Spain remained a superpower while it exploited America’s resources to finance its European adventures and brave its poor geography, but there was no way Spain, separated from its colonies by the Atlantic Ocean, could keep America as part of Spain forever. Just as the US seceded from the UK, America would eventually secede from Spain.

Third, American resources had a disadvantage: they held Spain’s development back, like any other country with a resource curse. Free silver meant easy money, and as a consequence its industries never developed, while the trade-centric UK and Netherlands were developing at breakneck speed. By the eve of the Industrial Revolution, Spain was a backward country.

Fourth, with an Atlantic Ocean AND a Pacific Ocean, it was impossible for the Philippines to contribute to the endeavor, and it was instead a drag on the Spanish economy.

And fifth, all of this was happening while the economies of the Northern European Plain were exploding thanks to their amazing geography and their equal access to the Atlantic.

In summary: the geography of the Iberian peninsula is bad for agriculture, trade, and centralized power, while Spain’s colonies were too far away and either lost Spain money or prevented it from developing its industry. Over the following centuries, Spain declined slowly as its northern European neighbors grew thanks to their better geography, more freedom, better management, and no resource curse.

The force that finished Spain off was the emergence of nations.

Books and Nation-States

When Napoleon swept through Europe in the early 1800s, he eliminated along the way the concept of Spain’s empire in two ways. First, he conquered and occupied Spain, eliminating whatever perception of might it still held. He undermined its monarchy, inserting thoughts of liberalism and republicanism that incited four civil wars over the following century and a half, brought about a 40-year dictatorship, and continues to attract political debates to this day.

Second, Spain’s colonies in America learned about the concept of nation-state, revolted, and gained their independence throughout the 1800s. One by one, Spain lost its colonies, until the new colonial power in town—a new nation-state called the United States of America—finished the old concept of Spain in 1898 by taking its only remaining colonies: Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

Spain’s Present and Future

Spain’s territory is bad. It’s so mountainous and dry that growing people, goods, and wealth is hard and slow. Despite its geography, Spain was lucky: the Reconquista pushed it to unite against the Muslims, and its position on the Atlantic gave it the opportunity to conquer America before any other country. Spain profited from the riches of America for four centuries, and spread its language and religion all over the world in the process.

But that wealthy empire was a mirage, an accident in time. It allowed Spain to live above its means for so long that its citizens forgot the harsh reality: Spain doesn’t have the geography to be a superpower. It was just lucky. After centuries as an oversized empire, Spain is back to reality, and its geography stings: the mountains are still there, and the differences between regions are important. When everybody is rich, nobody complains. But when a powerful empire dwindles, its components wonder why they’re together in the first place. The result is civil wars and separatist movements. After 500 years, it might be that Spain’s geography eventually prevails, and it breaks down into smaller pieces, like Catalonia or the Basque Country.

What is Spain’s alternative? To understand Spain’s path forward, we need to understand what made it successful. There are two things.

Spain won when it used its privileged position between Europe and America. Today, Spain is the bridge between Europe and Latin America. It leans on that role, and should continue doing so. Anything that supports the development of Latin America, and its ties to Spain, will be good for Latin America, Europe, and Spain.

More importantly, Spain won when its regions united to fight for their beliefs. That was true of the Reconquista when all of Spain’s kingdoms embraced each other for Cristianity. It should be true today too: Spain is united with its European neighbors to defend the values of a free world to make citizens happy. It should double down on that, focusing away from its internal tensions and into a future in the European Union.

Hopefully, in 100 years, the children of Spain will not be taught about the legendary Spanish Empire that was lost. Instead, they should learn how their beloved European Union was born out of the union of dozens of countries that were too small to matter alone, but which together shone a light on the world.

This is the 1st of a series of 4 articles on the topic that I have already written and will be publishing in the next week. I hope you enjoyed this article! But there are still so many questions unanswered:

What about Portugal? What’s its story? Why are Spain and Portugal not united? And why on the other side Catalonia is part of Spain?

Why does all of Latin America speak Spanish except for Brazil?

How come, in a country that contains so many languages, only one of them spread over the world to become the 4th most spoken language? Why that one and not another one?

Why is the accent of Spanish in Latin American the way it is?

Why did Spanish kingdoms conquer random places like Athens, Southern Italy, or Corsica?

Why are the Philippines mostly Catholic and the neighboring islands of Indonesia mostly Muslim?

Why does Spain still own islands and cities in Africa?

Why did Spain lose all its power in the 19th century?

Why does it have large cities over 2,000 years old, yet its capital, Madrid, was a backwater until 500 years ago?

How come Madrid is now the 2nd largest capital in Europe?

I’ll cover these questions in the next 3 articles. The next one will also be free, next week: A Brief History of Portugal. After that, I will publish both corresponding premium articles next week: Why Portugal Is Not Part of Spain but Catalonia Is? and Why Do 900 Million People Speak Spanish and Portuguese the Way They Do?Subscribe to read them!

Something similar happens in Greece, for example, and that’s why Greece was a thalassocracy, a country focused on the sea. Not much to produce on land. But Greece is much less massive than the Iberian Peninsula, and doesn’t have as many of these valuable regions.

The strongest Frankish emperor, part of the Carolingian dynasty.

To this day, in Spanish, when different people don’t take advice from anybody and rule their own little world independently, we call it a Reinos de Taifa. In other words, Balkanization. The fact that Spanish has a native expression for Balkanization (rooted in history) tells you everything you need to know about Spain’s fractious history.

I have found many reasons, but not one final explanation. If you have more insights to add, please leave them in the comments!

I’m assuming this given that this is true today, that the Earth’s axis has not changed in the last 5000 years, which is the key source of global changes in physical conditions, and that what I’ve read from the Romans is that their bread basket was more Egypt than the Maghreb. The coastal part of the Maghreb is and has always been fertile, so it was likely agriculturally productive, but maybe not in the way that Spain could be, but certainly not as fertile as all of Western Europe.

You can see this in their religious tolerance. Muslims were in general more religiously tolerant than Christians in Iberia. For example, the moment that Spain was united the Spanish king and queen kicked out the Jews.

The fueros were laws or rights that only the monarch could give to a territory, city, or person. Castilians could keep the land they conquered. This might have been one of the causes of the demographic explosion of Castile, which had eight million citizens at the end of the Reconquista to Aragon’s one million. This population, in turn, is one of the reasons why Castile pushed south faster than other kingdoms.

Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragon had married in secret in 1469, and became king and queen respectively of the Crowns of Aragon and Castile in 1479. The Crowns remained officially separate while they lived. When Isabel died, their only living daughter Juana should have inherited the crown together with her husband, the Habsburg prince Philip. But Philip died in mysterious circumstances soon after becoming king of Castile, and Juana was deemed crazy (“Juana La Loca”), which meant the crown reverted to Juana’s father, Fernando of Aragon, for 12 years until his death. When he died, both crowns of Castile and Aragon reverted to Isabel and Fernando’s daughter Juana La Loca, but since she was considered crazy, her son Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Roman Empire took over both crowns, uniting them for good.

Convinced by her husband. The story is crazy. I tell you about it in one of the premium articles next week.

So named because they became part of the Spanish empire during the reign of Philip II.

One he did not survive.

Tomas, I've been subscriber since Uncharted Territories Issue #1. This piece is exceptionally well written! A little long, but elegantly covers 2 millenia of geographical influence, accidents, with a line of optimism in the future. I absolutely love that direct flight from Madrid to Medellin CO, totally beats flying through the USA, and exemplifies exactly Spain's place in the world. What a great TLDR of the history of Spain!

Have you ever thought about writing a geographic influenced history book? A global narrative of this lens in textbook form? I'd totally homeschool my future children with that. :)

Just brilliant.I’d liked to have had this at school🙌