How to Understand France

This is the 2nd article in the series about France: If you missed the 1st one, go read France’s Bowels: A Secret Medieval Sect, an Angry Pope, an Opportunistic Lord, a Genocide, and Europe’s Destiny.

France is weird.

Why is it the biggest sea country in the world? Why was it the most powerful? Why is it not even the most powerful in Europe anymore? Why is it the only country in the continent that belongs both to the north and the south? While most nations in the continent have formed in the last couple of centuries, France has been around for over a thousand years. Why so long?

If we understand this, we can understand France better, but also a lot of why the world is the way it is today.

This is what Europe looks like today:

And this is what Rome looked like in 62 BC1:

Rome basically controlled the Mediterranean and whatever land was close to it, because it could easily travel the seas with ships. It took centuries of consolidation and technical innovations—including the famous Roman roads—before they could control vast and populated swaths of inland regions.

Note that they did control what’s today southern France, but nothing beyond the mountains. That’s what limited the Romans to the greatest extent: the mountains.

All of Southern Europe is basically mountains. They form an impenetrable barrier for a seafaring civilization.

Except for two holes.

5. The Two Passes

One is the Rhône Valley, carved by one of only two long European rivers that crosses these southern European mountain ranges (the other being the Danube, which ends in the Black Sea). The other north-south pass through mountains in France is the small area between the Pyrenees and the Massif Central, overlooked by Carcassonne.

This is crucial, because these passes are the reason the north and south of France are connected into one single country.

It is unsurprising that the first Northern European region that the Romans conquered was France: it’s the only one that had an easy pass through the mountains! Julius Caesar followed the Rhône river northwards2.

Eight centuries later, the Muslims used both of these passes to invade France.

These two passes, the one through Carcassonne and the other through the Rhône Valley, are the only two flat connections between the Northern European Plain and the Mediterranean. The ramifications have defined the power of France for a thousand years, which have in turn influenced the world for centuries.

The part of France that is on the Mediterranean, south of the Massif Central, is called the Midi. It has always belonged to Mediterranean culture. It had centuries more Roman influence than the north, centuries of Visigothic influence, Islamic influence, influence from the Crown of Aragon…

Rome also occupied northern France—for about five centuries—but it was a shorter occupation. And for the next 700 years, while the Midi was influenced by Mediterranean cultures, the main influence in northern France was the Germanic tribe of the Franks.

Without a pass between northern and southern France, these two regions would have remained as distinct as Germany is from Italy, or Poland is from Greece. You can imagine an alternate world where France (the kingdom of the Franks) stops at the Massif Central, and another country (maybe “Occitanie”?) controls the south.

This would have been one (or two?) typical Mediterranean country (Occitanie? Provence?), with its own national language (Occitan?), its capital (Marseille?), its wealth (from agriculture, trade through the Rhône and Mediterranean) and its history.

In this alternative world, there’s no country in Europe that straddles the north and the south of the continent. Northern France is not as populous. It’s not as rich. Remember that France was much more powerful than any other country in Europe primarily because of its population.

In this alternative world, France doesn’t have the wealth and population to tower over its neighboring countries. Maybe it doesn’t get a Marseillaise hymn to set fire to French hearts, or a Napoléon to lead them on the European battlegrounds (since he comes from Corsica, the Mediterranean island). Maybe the ideas of the Révolution don’t travel across Europe as fast.

Maybe Northern France focuses more on its Atlantic coast the way England and Spain did, and invests much more in its American colonies. Maybe it conquers a much more substantial piece of North America. Maybe some of the 13 colonies are French. Maybe France doesn’t sell these colonies to the US so easily in the early 1800s.

Maybe Spain, without such a formidable threat to its north, is able to keep its American colonies for longer. Without the inspiration from revolutionary France, the local Latin-American elites take much longer to develop their nationalistic ideals. Maybe without Napoléon´s invasion of Spain, the Spanish army isn’t as weakened and the Latin-American nobility doesn’t have a military opening for independence in the early 1800s. Maybe it takes one more century for them to get their independence. Or two.

Maybe the Holy Roman Empire doesn’t get humiliated by Napoléon. Maybe the impetus for German unification doesn’t exist, and Germany remains a loose confederation for longer. Maybe its leader becomes Austria, not Prussia, and its capital is Vienna, not Berlin. Without a newly-minted Germany built to fend off a powerful France, maybe there’s no WWI, and no WWII. Without world wars in Europe, maybe Europe maintains its colonies for far longer and never unites into the European Union. Maybe the US remains isolationist for much longer. Without a world war, maybe the communists can’t take advantage of the mess of WWI to take over Russia. Maybe there’s no US-USSR competition, no Cold War, no nuclear weapons dropped on Japan…

Alas, geography had other plans.

With these two passes through the southern European mountains, it was just a matter of time before the northern and southern parts of France would reunite. When this reunification happened depended on technology. Who would prevail depended on geography.

6. The Importance of the Northern European Rivers

Hands down, the north of France is a better piece of land for human development than the south.

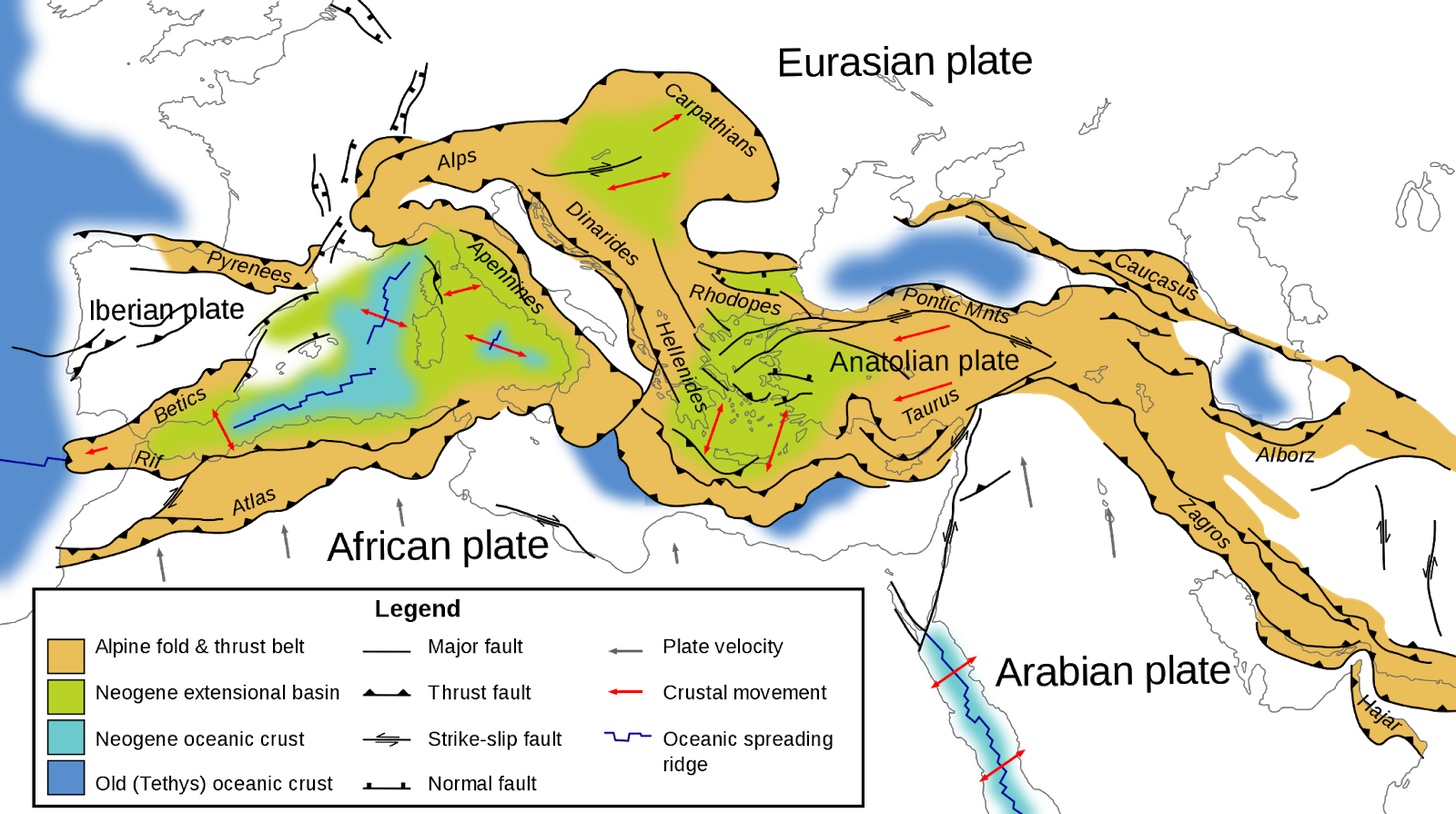

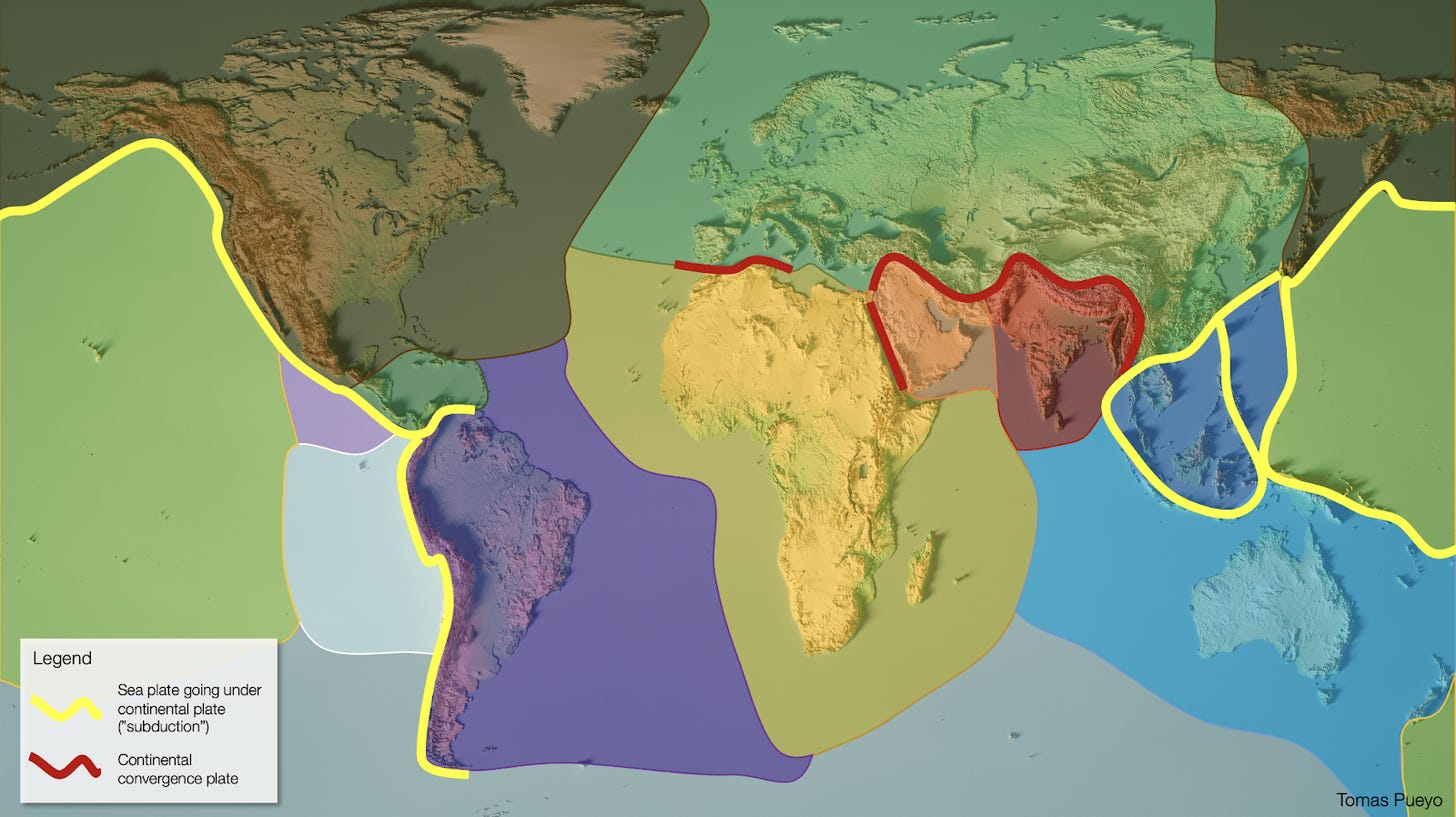

It all starts at the mountains in the south of Europe, which are caused by tectonic plates, as I explain in A Space-Crafted Chessboard.

The mountains are the result of tectonic plate movements. More globally:

So the tectonic plates push Southern Europe to the north, which creates mountains. But the north is flat, so water slowly flows from the mountains towards the northern seas. This creates the highest density of natural navigable waterways in the world3. Flat and irrigated land means lots of agricultural output, which means people. Navigable waterways means lots of trade, which means wealth. It’s not a coincidence that Northern Europe has the highest density of wealth in the world.

However, apart from the Rhône and the Danube, every big river flows from the southern mountains to the northern seas, and they don’t cross each other to form big river basins.

As rivers have been so important to irrigation and trade, countries have traditionally formed around them. You can see above how massive the river basin of the Danube is (big red area). It formed the 1000-year Austro-Hungarian power in combination with the Pannonian Basin:

If you go back to the river basins map, you can see the rivers that structure Ukraine (Dnieper river), Russia (Volga), and the many identities (Dutch, Prussian, Baltic…) that formed around the smaller Northern European rivers of the Rhine, Elbe, Oder, Vistula…

Why, then, does France fully control not one, but four of the biggest European rivers?

What’s unique about the Loire, Seine, and Rhône is that, despite their size, they all come very close to each other at some points. The Seine—the river that goes through Paris—is very close to the Loire through much of their length, which has connected their economies for centuries. The upper reaches of the Seine and Saône (a navigable tributary of the Rhône) are so close that their economies have also been intertwined for a very long time. One of the earliest canals in Europe was built here, in the early 1600s, to connect the Seine and the Saône.

Some of the biggest tributaries of the Garonne and Loire are also close to each other, and the Garonne basin forms the second pass to the Mediterranean, connecting it to the Rhône.

This is the most connected system of naturally navigable waterways in Europe. That’s why the economies, cultures, and politics of these rivers have been so close to each other for over a thousand years. You can trace back some continuity of France since the Franks established themselves in the region around the 3rd century AC, and became sovereign around 500 AC. That’s 1500 years of continuity, unrivaled across Europe.

The importance of rivers can be seen in another way: the cities.

Historically, cities were formed at the confluence of rivers: more water and more trade, as goods would arrive from one of the three branches to go to the others. The bigger the rivers, the bigger the city that sprung up there.

That’s why every French city is where it is.

Paris? Confluence of Seine and Marne, two of the biggest rivers in the country.

Lyon? Confluence of Rhône and Saône.

Bordeaux? Garonne and Dordogne.

Tours? Loire and Cher.

Nantes? Loire and Sèvre.

Angers? Loire and Maine.

Orléans? Loire and Loiret.

This map shows the population concentration in France. Virtually every center is a confluence of rivers. In fact, the population is a combination of things:

If there are mountains, there’s almost no population.

In the plains, the population follows the rivers, and concentrates on their confluences.

There are other important cities that have their own function. For example, Toulouse, on the Garonne, is its head of navigation: beyond that point, you couldn’t travel by boat any further. This type of location had an obvious trade advantage, as any transport beyond that point would start and end there. Le Havre is the port at the end of the Seine, relevant for trade in the Northern Sea. Eventually, Bordeaux and Nantes, close to the sea, would become the centers of France’s Atlantic trade, which brought them further wealth and population.

Paris, the Centralization Machine

But of all these cities, the best positioned was always Paris:

It’s at the confluence of the Seine and Marne, two of the biggest rivers in France.

The Seine is the most important river, as it is so close to the Loire and Rhône rivers that it connects to both of their economies. The French toyed with the idea of moving the capital somewhere else.

The Seine’s mouth is on the north of the country, which connects it to all the other economies of the Northern Sea, including those of every Northern Sea river: England, Netherlands, Germany, Baltics…

It also made it easier to get closer to all these enemies. It’s not a coincidence that the French nobleman William conquered England, that England occupied France for centuries, or that Germany reached Paris twice. Paris needed to be close to its trade partners and enemies.

It was formed originally on an island (l’Île de la Cité, where Notre-Dame stands), which made it easy to protect from invasions both from land and the river.

It’s in the middle of the Beauce.

The Beauce is the name of the central plain across Northern France. It’s the most fertile part of France, and one of the most fertile in the world.

All these reasons made Paris emerge as the capital of France. And a well guarded one.

7. The Highway and the Shields

Thanks to its position in the Northern European Plain, France is fertile and wealthy. But unlike all other countries in the plain, it’s extremely well protected.

Its position at the end of the plain means it is protected by the Mediterranean sea on the south, the Pyrenees mountains on the southwest, the Atlantic and North Sea on the west and north, and several mountain ranges on the east: the Alps, the Jura, the Vosges, and the Ardennes.

In fact the only easy hole in that entire setup is the continuation of the Northern European Plain, on the northeast.

On one hand, this was good because it enabled it to participate in trade and cultural exchanges with the other cultures in the region. On the other, it was a highway for invasions.

I’ve talked in the past about the importance of that Northern European plain and how much it has determined the existence of countries like Russia: without any mountains for defense, Russia wanted to grow as much as it could to develop a buffer. France, being on the other side of the plain, and with plenty of defenses, hasn’t needed to be as paranoid.

But everything between France and Russia is a fertile, wealthy, indefensible highway. What is today Belgium, Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are countries that have appeared and disappeared through the centuries: the Hansa League, Prussia, the Poland-Lithuania Commonwealth, Vlachs, Pomerania, Golden Hordes and Khanates, Pechenegs, the Novgorod Republic, Hainaut, the Teutonic Order, Habsburg Europe, the Cossacks, Courland, the Duchy of Warsaw, the Electorate of Brandenburg, the Holy Roman Empire, all its constituent territories…

Regions sandwiched between France and Russia have had to fight for survival against their neighbors for two thousand years. Convenient for France, who would always play other nations in that region against each other.

This is the main reason why France and Germany (Prussia earlier) were enemies until WWII: France didn’t want a strong threat to appear at its border.

This remains to this day France’s #1 priority: it needs Germany to be a very close ally, because it’s the only country that can reasonably threaten it. Every other major power would need to invade through seas or mountains, and that’s much harder.

This is mutual: Germany was founded specifically to fend off the French threat. It was the external enemy that Bismarck used to unite the German provinces. So much so that the founding of Germany was signed in the Versailles Palace, close to Paris, during the German occupation of 1871.

8. The Seas

France and Spain are the only European countries with coasts on both the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Up until 1450, the main sea for both of them was the Mediterranean, but it was much more important for Spain than for France.

France was more or less united, but as we saw, its main wealth came from the northern plains. That’s where it focused its attention. Meanwhile, Spain’s land is much more mountainous, so Spaniards naturally looked more to the sea. The Crown of Aragon owned half of Spain’s Mediterranean coast, the Balear Islands, Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, Southern Italy, and the region surrounding Athens, in Greece.

However, in the Mediterranean, the true powers were Venice, Genoa, and Constantinople. They were richer kingdoms, connected with the main trade route of the time: the Silk Road that passed through Constantinople, and then traveled to Europe through the city-states.

But in 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire, cutting access to the trade route to India and China. Europe needed another route.

The countries with the most incentive to find alternative routes were those farthest into the Atlantic and with the least fertile soil: Portugal and Spain. Portugal found the path to India through the south of Africa, starting its empire. Spain stumbled upon America.

Following these discoveries, France started exploring America in the early 1500s. But with its amazing land in the Northern European Plain, and as the main power in Europe, it didn’t have an existential need to expand overseas the way Portugal and Spain did. It did expand: Québec, Louisiana, Guiana, Caribbean… But the seriousness of its investment was revealed by England’s success, which started colonizing America only in the 1600s, but gained more territory and made it richer than France.

France’s fertile lands have been its blessing and its curse: they were so good that France never focused seriously elsewhere. It’s the first country to lose a colony to a local uprising (Haiti). It gave up the massive Louisiana territory to the US for little compensation. It gave up Algeria relatively quickly after a local independence movement erupted, despite a million French citizens living there. Its only South America colony (French Guiana) has always been economically challenged (the jungle land is terribly infertile).

By the end of the 19th century, the value of colonies was more obvious, so France did join the scramble for Africa. But it was more a competition with other European powers than a true investment.

The silver lining of all of this is that France has kept to this day a constellation of small territories across the globe: they were too infertile and economically unviable to grow big local populations and their identities, so they never had as big a decolonization push as other colonies.

This means that France, to this day, owns thousands of islands across five continents, and is the biggest maritime country in the world.

9. The Population

The irony of France’s maritime empire is that it’s the biggest in the world because it nevedr really cared about it. France cares about continental France. But unfortunately for it, despite having the biggest land surface in the European Union4, its population is smaller than Germany’s and similar in size to Italy’s and the UK’s.

Between the 1500s and the 1850s, its population was by far the biggest, which meant it had the biggest armies and it could prevail in most wars where it only faced one rival.

Then, in the 1700s, it pioneered the ideas of the illustration, including secularization and the concept of nation-state. The concept of nation-state allowed Napoléon to draft millions of soldiers to fight and win the Napoleonic wars, conquering most of Europe. The concept of secularization doomed its population, which would be surpassed by Germany’s in 1870, would kick-start the period in which France was not the main power in Europe anymore.

France’s current population it the least dense country in all the EU part of the Northern European Plain.

This smaller population is the reason why France is weaker economically than Germany—it’s not productivity: France’s productivity per worker is higher than Germany’s.

What does all this mean for the future of France?

Takeaways

The African and Eurasian tectonic plates push each other, forming the southern European mountains.

These create a bad terrain for agriculture in Southern Europe (hence its relative poverty), but an extremely high density of navigable waterways in Northern Europe.

These rivers have facilitated the emergence of plenty of independent cultures in Europe.

Many of them have remained independent, except in France, where all these waterways connect to each other. That has created a massive interconnected economy that very quickly grew its population and wealth.

Cities sprung up at every confluence of every river. Since the land is so fertile, and so many of these rivers were navigable, the population and wealth grew over time, especially in the northern half of France.

Within all of that, Paris was naturally the best positioned city, at the confluence of all these rivers, within the most fertile region in the country, and close enough to its trade partners and enemies.

If the Rhône had flowed northwards, and the mountains between the Alps, the Massif Central, and the Pyrenees had touched each other, there wouldn’t have been passes between the amazingly rich northern part of France and the Mediterranean coast. That would have made the unity of the north and south nearly impossible, France would be at least two countries, and what is today northern France would have never been as powerful as it has been.

The flat land in the north of the continent is called the Northern European Plain, and is some of the most fertile land on earth. France was gifted with a big chunk of it, making it remarkably fertile.

But unlike most other northern European countries, France is safely protected by seas and mountains.

Its only opening is through the northeast, what is today Belgium, and exposes France to Germany, a more powerful country because of its higher population that comes from its higher population density. This is why France will always obsess about Germany, and needs it as a tight ally in the EU to secure its existence.

That means that the seas were never the biggest priority for France, which is why it never invested much in its colonies, why most of them lost money, and why France is the biggest maritime country in the world: it kept islands here and there that were poor enough that nobody wanted to fight for them.

Despite a huge maritime empire to this day, France is and always will be continental France. And within that, what matters most to it is its northern half. But because of its early fertility transition, France is weaker than Germany, which threatens it.

Germany, meanwhile, can be threatened on all sides, so it benefits from good relationships with its regional neighbors—for example, with Russia. Giving up Russia is much riskier for Germany than France, and increases its exposure to France.

So France’s goal will always be to neutralize Germany, and it can only do that by embracing it as tightly as possible.

France’s destiny is to merge with Germany, and its tool is the European Union.

I hope you enjoyed today’s article about France. This is the 2nd one in the series about the country. The first one covers France’s Bowels: A Secret Medieval Sect, an Angry Pope, an Opportunistic Lord, and Europe’s Destiny. The 3rd and last article will cover France’s Cultural Cleansing: how it became the most centralized power in Europe. Subscribe to read them!

When I write this type of article, some of you write back to me and say “Tomas, this made sense centuries ago, but it doesn’t anymore!” and you’re not wrong. The dynamics I describe here are true to this day, even though they are weaker now than they used to be due to history’s network effects. The issue is not only what the reality is, though. It’s also how reality is perceived, and the assumptions under which the system has been created. Every lasting system in France has been shaped by these forces for over a thousand years. It will take decades, or maybe centuries, for these forces to weaken and the memory of these forces to fade. If you don’t believe it, simply look at Russia’s behavior. Its geographic dilemma is not relevant anymore, now that the risk of land invasion is so low. But after four centuries of constant imperialism, Putin just keeps the same mentality. He hasn’t internalized that the world has changed.

Before Caesar conquered France, which was called “Gaul” at the time.

The most valuable piece didn't come until the end, when he reached the northern plains. The pass through the Rhône valley is still very valuable and fertile, and was the perfect connection with Rome, so Rome put the capital of the Roman Gaul in Lugdunum (Lyon), where the Rhone meets the Saone, from where he could access the plain at the heart of Gaul.

This is in relative terms. Per square km. In absolute terms, it’s the Mississippi basin, as I explain in The Global Chessboard.

And in Europe only smaller than Ukraine and Russia.

What a gem you hid in the footnote “The issue is not only what the reality is. It’s also how reality is perceived.” This is the crux of so much human behavior at any scale. The extent unexamined past conditions our future. It’s why Buddhists joke “Don’t believe everything you think”. BTW section 5 with the maybes and consequences is incredible. It’s like an exercise in reverse futurism. How do you lay that out? A massive white board?

It's also fun to point out that the power and economic weight of France was great enough by the 17th century that it had become possible to *actually build a canal* from Toulouse to the Mediterranean. The Canal du Midi today is mostly just for tourism (the river cruise is remarkably fun), but when it opened in 1681 it was the first inland river route from the Atlantic Garrone river system to the Mediterranean. Technically, the canal was about 200m rise with around 80 to 90 locks (fewer today), and was fed by a perennial water source in the Massif Central so as to be a manageable flow year round. The basic design is pretty much exactly what wound up being implemented in Panama over two centuries later. It's really remarkable civil engineering, especially for its day, and it's worth a visit if you're ever in that part of France.