History’s Network Effects

The two main questions I’m asked about regarding Uncharted Territories are:

1: “Some days you talk about remote work, others about geography, yet others about media consumption. What’s the common thread?”

2: “You talk a lot about the influence of geography on history, but what about other things like technology?”

I’ll answer both questions today. First, I’ll quickly cover the vision for Uncharted Territories. Then, I’ll dive into today’s main article about other factors besides geography that have influenced history.

I hope you enjoy!

Where Is Uncharted Territories Going?

When I wrote my COVID articles last year, many wondered: “This guy is not an epidemiologist. Why is he writing about epidemiology? And why should we listen to him?”

I wrote about COVID because it was the best way to have a positive impact in the world. COVID was urgent but not important. Its urgency was so high that I focused on it. But as its urgency waned, it was time to turn to what’s important in the long term.

In the launch article for this newsletter, Enter the Uncharted Territories of the 21st Century, I mentioned the topics I care about, but I didn’t connect them. The connection, to me, is that a series of megatrends are going to severely change the way we live in the next 10-20 years. Our societies will get completely reshaped as a result. I want Uncharted Territories to be the place where we prepare for those changes and, if possible, where we gather to influence the direction of our societies. So what are these changes?

Automation and globalization have already dramatically reshaped our world. We’re more productive and the world is richer, at the cost of a lot of middle-class jobs in developed economies, especially among blue-collar workers. Automation creates fantastic new services, but not fast enough to hire all the people who will lose their professional options. That has driven income inequality in many developed countries, populists take advantage of to take power around the world.

Remote work is about to do something similar, but for white-collar workers. More work offshoring, followed by more automation, leading to lots of people with access to only low-paying jobs, to more income inequality, and to more political instability.

This will reduce governments’ taxes: the middle classes will make less, while those making the most money will be mobile, so they will be harder to tax: they will leave if they’re too high. This occurs at the same time that:

People are healthier and live longer, so they need more support for retirement and healthcare. This might become dramatic as new aging technology reverses aging.

Fertility is low, so there are fewer workers to tax.

Populism results in an anti-immigration sentiment, just as immigrants will be needed to replace the workers we don’t have.

Cryptocurrencies will make it even harder to tax income and wealth.

This will result in dramatic budget imbalances, starting with the countries with the biggest share of GDP mediated by the government. This will result in fewer and worse-quality services provided by Western governments, and in more class antagonism.

In the middle of that, we will need to balance other threats, such as Global Warming, the transition from a world where there’s only one superpower—the United States—to a multipolar one, or changes in warfare.

All of that will undermine the power of nation-states. Other centers of power will replace them little by little: (sovereign) individuals, international organizations, and companies. New ways to organize ourselves will emerge, such as DAOs, city-states, or cloud sovereignties. This is a change as radical as the end of the Roman empire or of feudalism.

All of this has the potential to create a chaotic, unequal, and hostile world. If we want to guide it in a positive direction, we need to understand in detail all these big trends and design a system that is realistic, yet makes the world a better place.

This is what I want to achieve: design such a system. But I can’t do all of it alone. I need your help. Writing about it for you helps me understand all these trends better. Your support, your comments, your emails, your thoughts, your debates improve all of our thinking.

After I wrote the first COVID article, Why You Must Act Now, a team of volunteers came to help me write all the following articles. I couldn’t have written all these articles without them. I would like to replicate that for Uncharted Territories. I think together we can have a huge impact, so if you consider yourself an expert in any of these areas, and you’re interested in helping me understand them, please respond to this email to let me know.

History’s Network Effects

In our last GeoHistory articles, I’ve emphasized how much geography has impacted History. But if geography was the only factor, you would see cities and civilizations springing up randomly wherever local conditions are great. You wouldn’t see some areas become dramatically more advanced than others. You wouldn’t see consistent patterns.

But patterns exist. I’ve hinted at some throughout the series. It’s time to understand them better. What are the mechanisms of development? How have they impacted history?

Mechanisms of Development1

Food

This is the one we’ve covered the most. The more food, the more people.

Consider the Nunamiut and the Tareumiut. They were closely related tribes of Northwestern America, with similar genetics and language. But the Nunamiut lived inland, while the Tareumiut lived on the coast.

Inland, there weren’t that many resources. The biggest source of food surplus was during the caribou migration. The Nunamiut didn’t have a complex society. They tended to live in separate families, but during the caribou migration, they would band together to hunt them and feast on their meat. Outside of that, they tended to survive on whatever resource they could find. This is a typical hunter-gatherer society.

However, the Pacific coast had whales, and the Tareumiut hunted them. More food meant a larger population2.

Technology

But it’s not the only thing more food meant. To hunt whales, they developed boats, harpoons, seal skins that they filled with air, to stick them to the whales to tire them… They developed new technologies to harness the more abundant food opportunities.

Farther south in the American Northwestern Coast, natives had even more accessible food: halibut, cod, herring shellfish, sea otters, whales, candlefish… Rivers were teeming with salmon. Inland, they had bears, elk, deer…

But they couldn’t just hunt these animals with their bare hands. They needed hooks for the fish, cages for the salmon, traps for the bears, spears, etc. So gradually they developed these technologies to harness the natural resources available to them. Most of these technologies have emerged independently in many places around the world: when the resources are there, humans develop the tech to get it.

The more technology these tribes developed, the more resources they could extract, and the bigger the population they could support.

If there’s enough food in the area, you might even be able to stay put instead of roaming all year long chasing food. Sedentary life comes with huge benefits. For one thing, you may have much more time in your hands since you don’t have to search for food and move. More importantly, you can accumulate wealth.

Infrastructure & Wealth

Northwestern natives built houses that were frequently above 200 square meters (~2k sqft), and up to 400 m2. You can only do that if you stay there year- round, for years and years. And the only way to stay is if enough food is available to you. They also built other public works, such as smokehouses for curing fish, cellars for storing curd fish, or watertight cedar boxes for berries. The more food you have, the more you can invest, the more wealth you build, and the more productive you are, feeding the virtuous cycle.

Also, the more surplus of food there was, the less time people had to spend getting food, and the more they could spend it on side gigs.

These side gigs included many things. What would you have done in their place? Maybe as a fisherman you’d think of ways to improve your harpoons and fish hooks.

Maybe you would notice berry bushes and spend your free time getting these delicacies. Maybe you would want to make sure animals don’t eat your berries, so you plant a fence around them. Maybe you would want to have the plants closer to your backyard, and move them.

In both cases, spare time allowed for many things, among which was time to specialize in an area and improve technology, which increased productivity. And the more people there were, the less time they all had to spend on the same area of focus, and the more each person could improve their thing.

Maybe instead of improving your fish hooks or your garden to produce food, you liked going to the beach, gathering shells, and making necklaces out of them. Maybe others in the village enjoyed them, and were willing to give them some food in exchange. So maybe you’d start making more and more of these necklaces… to trade.

Trade

If you have too much whale meat or too many shell beads or too many berries, they’re not useful to you. But they might be very useful to others in your village. As far as I know, trade has been witnessed in all communities, whether with money or bartering, because it helps get an even bigger diversity of products.

And the more people you trade with, the better. What if a neighboring tribe has delicious caribou? What if they have some medicinal plants? Ropes? Cloth? You want them, so you will focus on producing more of your own things to trade.

The more of these tribes are around, the more different items you can get, and the bigger the incentive for you to produce your stuff. Also, the more you will be interested in specializing in your craft, so you can be more productive and create more items that you can trade for other ones.

Also, the more food surplus you have, the more free time you have to dedicate to these side gigs. But you will only dedicate it if you can trade your items for somebody else’s.

So now you have a virtuous circle where the more food, the more spare time, the more specialization, the higher the productivity, the more items you can create, the more you can trade them, the more other items you can get, and the more you can accumulate wealth. With more wealth, you can invest more in infrastructure, which increases your productivity, which increases your access to natural resources, and increases your population.

Government & Social Coordination

But not all the food was easy to get. Going back to the Tareumiut: one single person couldn’t hunt a whale. Not even a group on a boat could. It took the Tareumiut the coordination of several boats, owned by different people, with specialized roles like harpooner or helmsman. People had to coordinate to build the boats and man them and attack together and split the proceeds. This is a much more complex organization than the Nunamiut’s caribou hunting. The level of social complexity emerged where the resources were there to be exploited.

This happened throughout the world. For example, it was better to build big cages to capture salmon. But no single person could do that, so people gathered to build them. Cellars, granaries, or later irrigation works are other examples of public works that required complex social coordination.

Frequently, one person had to emerge to coordinate others. For whale hunting, it might be a boat owner who coordinates with other owners for a hunt and then distributes the food to all the participants. What if they needed to build boats? Sometimes they might have given tokens to represent a promise of food after the hunt. These are early forms of government.

Social complexity and government also appeared in other ways. For example, through trade. When pirates and marauders disrupted trade, they reduced wealth. Traders and local governments then organized to eliminate the threats. Romans expanded into the Dalmatian coast, for example, to stop pirates. It’s one of the reasons why later both Venice and the Hanseatic League appeared and gained power. They wanted to secure trade, and for that they needed defense. Defense requires organization, which is institutionalized as a government. Trade begets government.

More generally, when a ruler can enforce predictable and just law, people know what to expect, their risk is reduced, and they are more likely to start businesses. That creates a surplus, and part of it can be captured via taxes, which funds further expansion of the government, which achieves even more safety and justice, in another infinite loop.

Easy Access

Unfortunately, trade doesn’t take place if you have few other tribes around you. In such circumstances, it takes a very long time to reach the other tribe for trade, time which you might not be able to spend because you don’t have that much food surplus. For example, if you can accumulate food for two weeks but the closest tribe is three weeks away, you aren’t going to trade. If they’re one day away, you will.

Without that trade, your incentive for productivity is limited. The types of items you can accumulate are limited. The technology you learn from other tribes is limited. The wealth you can build is limited, and the entire system grinds to a halt.

The Flywheel

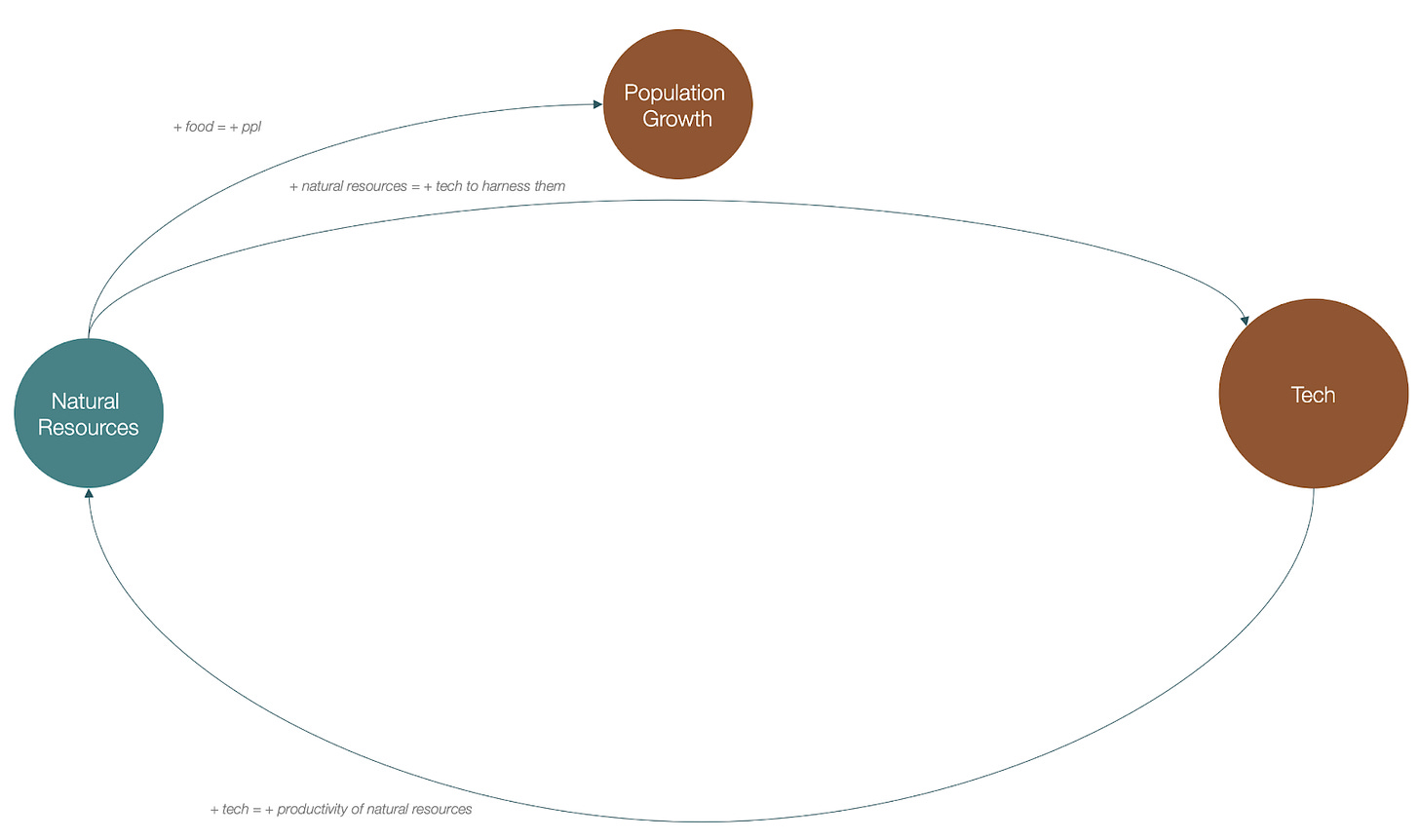

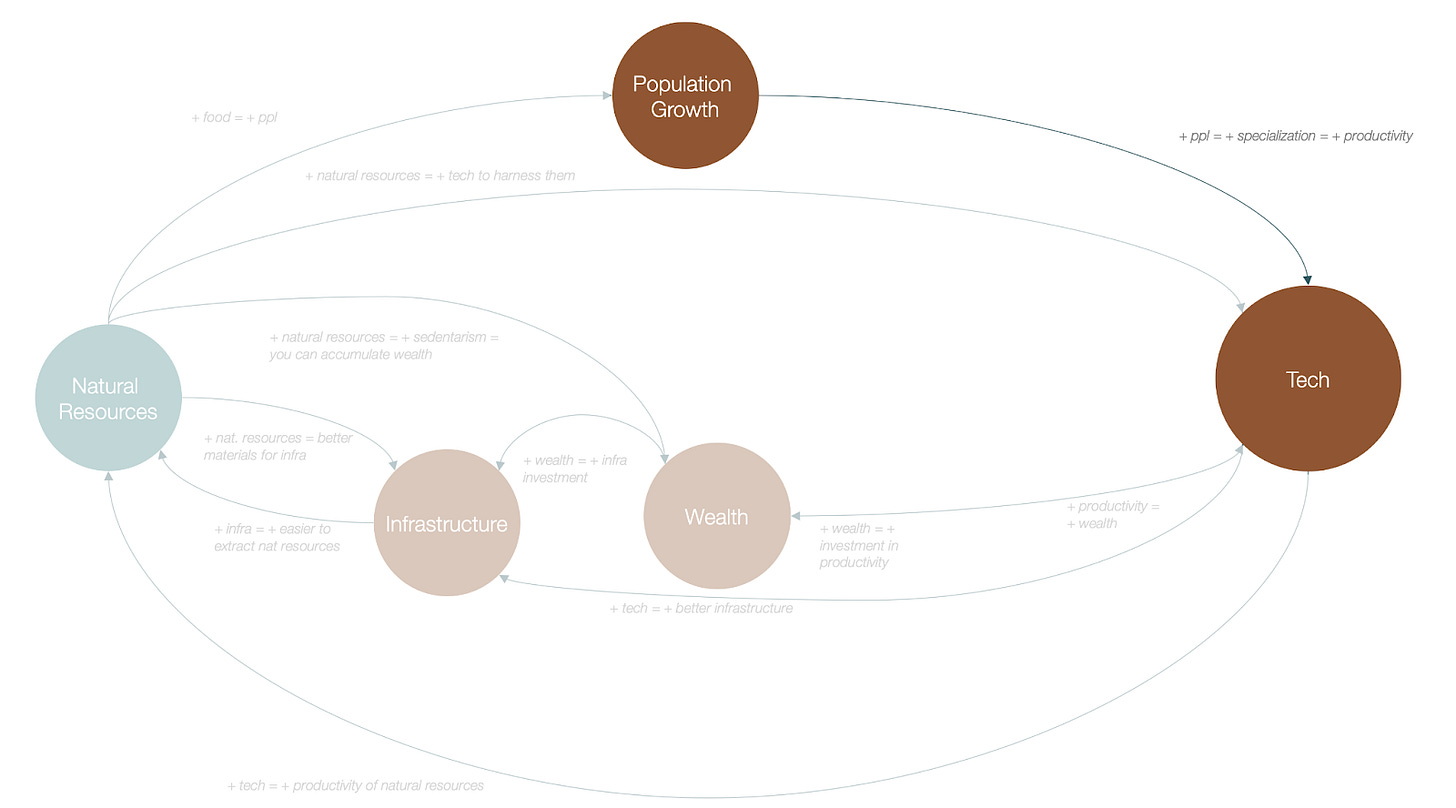

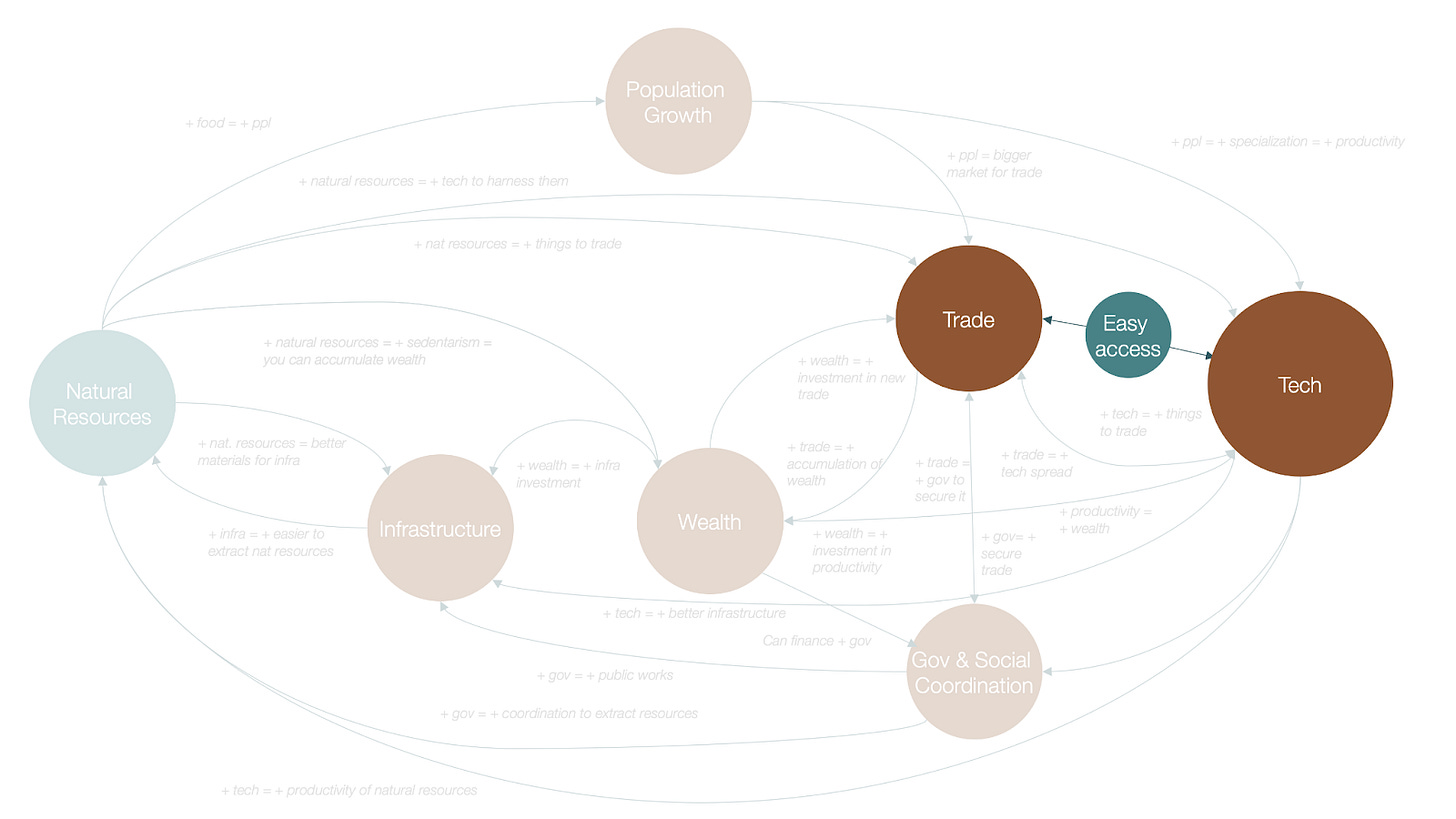

In summary, this is what development looks like.

It is not meant to be exhaustive. There are many more factors, and many more interactions between them3. Rather, it’s meant to illustrate a key point: this is a flywheel.

Every arrow in this diagram reinforces the other ones. The more each of them takes place, the more the entire system accelerates.

The Network Effects of Development

Accelerating Growth

If this is true, what you should be seeing is an acceleration of the rate of technology development and economic growth over history.

This seems like an obvious statement, but the consequence isn’t as trivial: the places with the best initial geographic conditions, such as great natural resources and easy access to other populations with natural resources, will have an advantage that is nearly impossible to beat, because they get the flywheel turning early on, and then it accelerates and accelerates. By the time they reach the industrial revolution, your society might still be perfecting harpoons, and the only difference was just slightly better initial conditions.

If this flywheel effect was true, you’d see a consistent acceleration in the rate of innovation worldwide. This is indeed what you see.

The rate of technological innovation has risen slowly for tens of thousands of years. In the Middle Paleolithic, between 300,000 to 30,000 years ago, humans produced one invention every 20,000 years or so. In the Upper Paleolithic, between 30,000 and 12,000 years ago, it accelerated to one every 1,400 years. By the Mesolithic, between 12,000 and 5,000 years ago in Europe, it was one every 200 years.

Between 0 and 1,000 AC, the economy grew at 0.1% per year, which means wealth close to tripled between these dates. At the time, growth was slow enough that nearly all growth in the economy translated into population growth, so this graph of the world population’s growth rate is a proxy for the growth of the economy.

As you can see, that growth accelerated over the centuries in an exponential way. And this is the growth rate accelerating. The result in the total economy is this:

Of course, that growth has not been even over the millennia. When there’s a cataclysm such as a change in weather patterns, a terrible war, or other catastrophic events, things can go back momentarily. But in the long term, the arrow of development only goes in one direction, and that direction is exponential.

Why did only one area of the world reach the industrial revolution then? Because of this acceleration.

Imagine that one area has substantially better natural resources and easier communication to other communities initially. With that better original endowment, that area will develop faster than others. As we saw, the more food, the more people, the more tech, the more wealth, the more infrastructure, the more everything. This is divergent growth, not convergent. A small change in the initial conditions, in those teal bubbles, can have a dramatic impact in the outcome. This is typical of network effects.

Network Effects

What are network effects? When adding one item to a network makes the entire network more valuable. The more you add, the more valuable it becomes, faster.

For example, when a new person gets a phone, everybody else is better off: they can all now call one more person.

The same is true for a marketplace: Add one more home to Airbnb, and every Airbnb traveler around the world can benefit from it. The more homes, the more travelers because they have so much choice. The more travelers, the more homes, because they have more potential customers.

The network effect is so powerful, so hard to stop once it’s started, that it’s behind ~70% of the value created by technology companies. Google, Facebook, Netflix, Youtube, Uber, Airbnb, Twitter, LinkedIn… all companies with network effects.

The same is true for all these factors of development. The flywheels between food and tech and people and wealth and all the rest become more and more valuable as more factors are added to the network.

Imagine if on top of that, instead of one network with these network effects, we combined several of them. That’s what happened in Eurasia.

As I said in The Global Chessboard, Eurasia is much more connected than any other continent because it has such a long extension in the same latitude and without insurmountable barriers. That allowed technologies to spread across it, while those of other regions remained isolated and didn’t learn from each other.

Imagine network effects connected to other network effects, all feeding into each other in an endless circle of accelerating growth.

This video shows the cities created in the world every 25 years, between 3,700 BC and today.

Original site, where you can play with the controls. From a Yale dataset.

You can see many things:

Cities appear independently in different areas: the Middle East, India, China, Mesoamerica, the Andes, and maybe Egypt, Western Africa, Southeastern Africa, and the Mississippi.

All these areas have a great geography to start with.

The better the geography, the earlier cities appear, in general.

An early advantage, when cities appear earlier somewhere, is very hard to make up for.

The higher the density, the faster the growth. This is obvious in Mesopotamia, which is the first area to grow cities and also the one spreading them the most, bringing civilization to Europe and connecting it with China.

Compare Eurasia with what happens both in America and Africa. The process starts later and is slower.

Economic development has escape velocity. Because of that, the most likely place for the industrial revolution was Eurasia. But give it enough time, and Mesoamerica, Africa or Australasia would have eventually developed it too. How do we know? Because they were all on the same trajectory.

Each of these areas had groups of people in different stages of development. Some had only hunter-gatherers. Others developed kingdoms. In all of them, you can see signs that agriculture or trade were evolving, with the more advanced societies developing more advanced technologies such as money and writing.

Why is all of this important? Because if we understand the components and speed of development, we can start predicting what comes next.

The Takeover of Technology

It’s time to add one layer to our system: bubble sizes!

The number one thing that matters to hunter-gatherers is natural resources. If there aren’t enough, they have to move. They develop some technology, but barely. They can’t accumulate wealth or infrastructure because they have to move. They can barely trade because they don’t have enough surplus food, or because they’re too far away from other tribes.

Where there are enough natural resources, eventually technology emerges. Different tribes close to each other start trading. Other bubbles gradually appear.

Over time, technology and trade become more and more important. Some areas start specializing, even if they don’t have all the natural resources they need. For example, as I shared in A Brief History of the Caribbean, Mexico under Spanish rule specialized in silver mines, Cuba and Puerto Rico specialized as trading logistics ports, and Hispaniola specialized in sugar.

Today, this is even truer, with specialized areas doing exceptionally well: London, Cayman Islands (finance), Singapore (trade, finance), China (manufacturing), Bangladesh (textiles), ... Natural resources still matter4. But more and more, what we’re seeing is that tech (and its trade) are taking over.

Tech is eating the world

Eight of the most valuable public companies in the world are technology companies5. Just 20 years ago, only four were. The digital economy consistently grows as a share of GDP. It’s still at the beginning, with only 7% of GDP today, but it’s growing fast. You know all these tech unicorns you hear about? All this remote work happening?

Tech doesn’t need much infrastructure. It doesn’t need big ports and reliable roads. It just needs a good broadband connection, and soon we won’t even need cables for this thanks to Starlink, which will provide good access anywhere in the world. Bye bye infrastructure bubble6.

Tech doesn’t need natural resources. Google, which could operate from anywhere in the world, had $180 billion in revenue in 2020. It doesn’t need many natural resources to achieve that.

Tech doesn’t need a big population. Israel’s 9 million people have more cutting-edge technology than most other Western countries. Now that the entire world is connected, there is no huge advantage in growing the local population.

Tech doesn’t need wealth. One person with a computer can create a trillion dollars of value, as Satoshi Nakamoto proved by creating Bitcoin. Instagram was sold for $1B with 12 employees. WhatsApp had 32 employees and sold for about $20B. Vitalik Buterin, the creator of a piece of code—Ethereum—is worth $21B. Now, with tech, it’s cheaper than ever to create wealth out of thin air.

As for trade, historically the biggest drivers of transportation costs were mass and distance7. Something heavy and far away was expensive to trade, and vice-versa. The more valuable something was per unit of mass, the longer the distance something could be traded. That’s why jewels, gold, and silk were some of the first things to be traded far away. That’s why Spaniards could only plunder silver from Mexico, whereas plantations weren’t viable.

But as technology develops, we pack more and more value per gram. Compare the value per gram of milk to the value of a car. Or a phone. That density makes trade barriers less and less relevant. To the point where we’ve reached infinite value per gram with internet, since mass is zero and distances don’t matter.

We will always need trade, because we will always need food and shelter and clothes and electronic devices. But the more time passes, the more things are automated, the cheaper physical trade becomes, the cheaper technology trade becomes, and the more tech takes over.

The consequences of all of this are brutal.

When I wrote the articles about the importance of geography in history, I wanted to highlight something crucial: the weight that geography has had on history is overwhelming and we don’t even realize it.

But once we realize it, we can understand how dramatic the change is from the old world to the new world, where technology takes over.

Take one example: fresh water. It’s the single most important resource of all time. And yet it might become mostly irrelevant in the coming decades. It is now cheaper to build new solar energy generation than to operate existing fossil fuel plants. With that, reverse osmosis becomes viable as a key source of fresh water, not just in desertic areas like Israel or Saudi Arabia, but anywhere there’s sun. Suddenly, one of the biggest causes of natural resources scarcity disappears thanks to tech.

One thing—geography—greatly influenced our history for millennia. Then, little by little, a slew of other factors started mattering more and more. And now, suddenly, in a matter of decades, one single factor is taking over again: technology.

The constraints of geography are shrinking, and the world is becoming a single place. This was true 2,000 years ago when the Silk Road took shape. It was true 500 years ago, when Columbus crossed the Atlantic. It was true a century and a half ago, when the telephone and railroads and the telegraph appeared. It was true when nuclear weapons nearly wiped us all out. And it’s certainly true now with the internet.

This change is exponential. We don’t feel it because it’s hard to feel an annual 2% improvement in productivity. But over decades, the impact is massive. Everything we know, everything we take for granted, will be pulled from under our feet. Those who remain in the past will become insignificant. Those who understand this can prepare for that world. They can make the right decisions for themselves and their loved ones. They will thrive.

Which group will you belong to?

One of the best books on these topics is Nonzero, from Robert Wright. His books Nonzero and The Moral Animal are among the most impactful on my way of seeing the world. I highly recommend both.

You’ll notice I generalize food to “natural resources” in the graph. Food is a key subset of other natural resources, in that it helps more directly to grow the population. Aside from that, there’s a continuum between food and other natural resources. In one extreme, you have staples like meat or wheat. In the other, jewelry, whose value is strictly social (status) and doesn’t have other functional benefits. But what about berries? They’re food, but seldon eaten for survival. Licorice? Chocolate? Coffee? Tobacco? Cotton? The more we move in the gradient between food and jewelry, the less it’s just about directly feeding the population, the more it’s about fulfilling other needs, and the more trade is necessary to enable population growth. Nevertheless, since all these natural resources have been harnessed since very early, and have a function that differs from food only in degree, I bundle them together.

Which ones? Please let me know in the comments.

But even there, specialization and trade are also crucial, such as in Saudi Arabia (oil) and Botswana (diamonds), which depend on trade with other countries to exchange their one resource into others.

Depends on the day. The point is they’re concentrating more and more wealth.

Obviously not disappear. You still need roads and airports and homes and water and much else. But if you’re trading mostly internet stuff, you don’t need as much infrastructure.

A combination of mass and volume, really.

You may have seriously neglected or at least underweighted a key variable in the flywheel: energy. There is a very direct relationship between increasing density of energy for work and GDP growth. Most work used to be done by human bodies, until we domesticated animals like horses and oxen, and then developed technologies to make animal power more efficient (yokes, carts, horseshoes, etc.), and then stalled for centuries after that. Which is why GDP only increased 0.01% per year and population growth was gradual and extremely variable. What changed in the 18th Century? Coal and then the steam engine, of course. But even before that, there was also the mini-revolution of wind and water-wheels, which created a boon in Europe in the late Middle Ages and were a contributing factor to the Renaissance.

Dense sources of energy for work continue to be key for the "technology eating the world," which you (incorrectly) assert a miraculous immateriality. At the far end of every Google search is ultimately organic matter that was densely compacted into energy-rich muck over the eons in a few choice locations on the planet.

Google, like the Internet itself, is a dense web of servers and fiber optic cables. It is material. It is also energy. The solar PVs that will "solve" the issue of freshwater's uneven distribution are energy embodied. They are created from silica, which is mined through an energy-dense process in places like Western China. Places are are desperate for the coal, diesel, and other energy-dense mediums that make technology and its cheap mass production possible.

Israel, Singapore, and the mega-region around London are fed be unimaginable amounts of energy, almost all of it imported in some manner. They do not exist in an energy vacuum. Where does their electricity come from? Where do all the computers come from? What is making the container ships and airplanes that deliver them go?

Silicon Valley is located in California, which was one of the first regions in the world to commercialize refined petroleum products at scale. To this day, California, though famous for its environmental regulations and "green industries" like Tesla, remains a significant source of "dead dinosaur juice." Silicon Valley is so-named because it used to be as Taiwan is today, the preeminent manufacturing hub for a very material thing: silicon chips. Mined from the earth and then manufactured into delicate instruments with exacting precision using massive amounts of energy from the oil wells down south. The legacy of this persists today: the sleek corporate campuses of Silicon Valley still sit atop some Superfund sites and are still reached by Stanford graduates in cars and Google Buses mostly powered by gasoline. Their world of bits and code is still a material one, built atop an empire of oil.

Energy isn't evenly distributed. The English industrial revolution was built on rich seams of coal, like the current Chinese one is. The United States has been blessed with the black rocks, as well as an even more valuable black liquid: petroleum. Other advanced economies (e.g. Germany and Japan) also lean heavily on coal, but have entirely outstripped their own indigenous supply and are perilously dependent on imports, oftentimes from potential adversaries or vulnerable supply lines.

Green generation technologies can be more evenly distributed, yes, but they are like batteries. They must be created with a massive infusion of energy, up front. Energy that, right now, is created by consuming other dense, material stores of energy. They are essentially energy that has been "stored" in a generation medium (PV, wind turbine, hydroelectric dam, or nuclear plant). They harvest energy from the sun, wind, water flow, or atomic bonds of atoms... but only after we expend massive amounts of energy from other sources creating, feeding, and maintaining them. Where does that initial energy come from?

And, unfortunately, current green energy technology doesn't create a perpetual energy flywheel. Nuclear power plants take decades to build and only last as long before decommissioning (again, another extremely energy-intensive process). Solarvoltaics last up to 30 years, but with decreasing performance. Turbines, subject to extreme forces, last much less long. Li-Ion batteries last mere years. So, again, green energy is more like a battery than a lump of coal. You fill it up with energy up front, use it for a while, and then must replace it. This is a tyranny of physics that isn't addressed in your model.

This reminds me of this interactive simulation: https://ncase.me/loopy/