A Brief History of the UK

In honor of Queen Elizabeth II’s passing and the UK’s economic crisis, I wanted to dig into why the UK is the way it is.

Why did the UK brexit from the EU? Will it ever return? Is the UK’s future closer to Europe or the US?

Why is one of the world’s most powerful countries still a monarchy?

Why do so many people wrongly mix England and the UK?

Why does it have separatist movements among the strongest in Europe?

Why is its relationship with Ireland the way it is?

Why is London—a city in a small plain of a small island—one of the biggest megalopolises in the world?

What makes English unique as a language?

Why was the UK’s parliament one of the earliest?

Why did the Industrial Revolution start there?

It’s impossible to condense 2,000 years of history in one article and not miss important things, or get everything right. So please, feel free to add color where you think it’s valuable and to correct me where I make mistakes!

Alright, let’s start from where we always start:

Look at the map with intent. If you were to guess from it where the population is in the British Isles, you’d assume it’s mostly on these plains of southern Britain, because the flatness and rivers are conducive to agriculture. Maybe also some people would be on the flat coastal plains and big cities on the biggest rivers, and some in Ireland. Something like this:

That is partly right. But much of it is not at all like that! If we focus only on the UK:

The southern plains are indeed heavily populated, but there are vast regions that barely have any population! Meanwhile, some mountainous regions shouldn’t have much population, but actually have a lot. What’s happening?

The United Kingdom of Mountains, Islands, and Plains

Islands

It makes sense that these islands are somehow united. The neighboring continent is one big mass, and they’re the only big islands around. If there had been many more islands, maybe a more diverse identity could have emerged. But as is, these islands are big and quite isolated, so it makes sense that they diverged in identity from the rest of the continent.

For the same reasons, it makes sense that Ireland would develop its own identity.

Given that most of the plains are in a single region, in the southern part of the big island (Great Britain), you’d assume this is where most of the population is, and that it would have developed a strong identity. This is England. It’s why it accounts for 85% of the population, why most of the economy is concentrated there, and why people sometimes confuse England with the UK.

Mountains

The farther you go from that center, and the more the terrain changes—especially if it’s mountains—the more likely a different identity would emerge.

It makes sense that hilly Wales in the west and mountainous Scotland in the north would create their own identities and early kingdoms. It also makes sense that the gravity of England would absorb Wales earlier on, and that Scotland would remain much more separate: Scotland is bigger, more mountainous, and farther away from the gravitational center of the English plains.

So that explains why Wales joined England in the 1200s and fully in the 1400s, but Scotland only in the 1700s.

The Formation of Scotland

If we follow the Roman progression, we can really get a good sense of the formation of Scotland.

The English plain is flat and compact, so it was easy to conquer and to build roads on it, which increased both its capacity for trade and political unity.

But north of this plain are mountains, the Pennines. Mountains were bad for Romans, because they’re hard to conquer. But not conquering them left the mountain people there, who had the bad habit of attacking the plains whenever they chose. So Romans wanted to “pacify” them.

That was the function of the Hadrian Wall1, started in 122 AD: It isolated the Pennines from the mountains north of it, which divided the locals, contained the northern threat, and gave the Romans time to co-opt the mountains south of the wall.

Why did they build that wall there? You want your wall to be as cheap and defensible as possible, so you want to build it on a flat area and across a narrow neck.

Once the area south of the Hadrian Wall was controlled, Romans wanted to go farther north and do the same. But it turns out that the farther north they went, the higher the mountains became. Luckily for them, there’s yet another—even narrower—neck in Scotland’s lowlands. That’s where the next wall, the Antonine’s Wall, was placed, and the Romans didn’t venture much farther. The mountains beyond that were the Scottish Highlands, even farther and higher than what they had conquered before. They gave up.

From that logic, you can follow the formation of the Scottish identity:

Britain is a narrow island, oriented north-south, which means different climates and long logistics chains. Hard to control it all.

The farther north, the more numerous and higher the mountains were.

Which also means fewer roads.

These factors mean that the farther north, the less cultural connection with England.

This terrain is in fact very conducive to internal strife. Which is why Scottish union was never a given.

Arguably, it was the existence of a united enemy to the south—England—that unified Scottish sentiment.

So that’s Scotland. It makes sense that it has a small, independent population. But what about these huge English plains that should be hyperpopulated but aren’t?

The Fens

There are three reasons for that.

The first one is that the terrain is too flat.

Look at the sea. Can you see the light blue that surrounds the British Isles and covers the entire North Sea? The Atlantic is much deeper west of Ireland. Indeed, the islands of Great Britain and Ireland belong to the tectonic plate of continental Europe and the North Sea. All of that is very flat and not very deep. This is why the Netherlands could easily conquer land back from the sea.

Just 10,000 years ago, before the end of the last glaciation, there was land where the North Sea is today!

A big chunk of what’s now called East Midlands and East of England is barely a few meters above sea level. As a result, most of that region was prone to inundations, which made it dangerous and hard to cultivate. The most exposed were The Fens, composed of marshes frequently inundated by seawater.

The rivers flowing into the North Sea were shallow, full of sediment, and couldn’t be easily navigated.

If England had invested in infrastructure for this region, such as drainage and river embankments, it could have developed the way the Netherlands did, which became the richest country in the world in the 1600s. But those investments in the Fens only came in the 1600s, and the region hasn’t been able to catch up in population since. But it has become the most fertile region in England. So why didn’t it receive investments earlier?

This leads us to the second reason why eastern England is not heavily populated: the gravity of London.

London’s Competition

London might have been lightly populated in ancient times, but it was the Romans who made it the capital of Britain, Londinium. They located it at the key point where the river Thames meets its estuary. This was ideal, as it was also the furthest east they could build a bridge, but it also allowed the city to manage all the river trade from upriver. They placed the core of the city in an elevated area that could be well defended and wouldn’t flood.

Before the Romans built that London Bridge2, it was a natural border between tribes and chiefdoms. But once it was built, it became a key passage across for both sides. That made it a natural trading hub on and across the river, but also a strategic point to be defended.

The bridge was not the only piece of infrastructure the city needed. The Thames was wide and marshy. It needed infrastructure investment to gain space on the river, to make it narrower and more navigable. All these investments took centuries and were costly for the treasury, but they attracted population and trade, bringing people in from the surroundings, including eastern England.

Nevertheless, London suffered for centuries, as it was depopulated, sacked, and abandoned. Why?

The Channel

It would seem that a waterway like the Channel should protect England from invasion. That was true, but only before those on the continent developed their boats, and after England developed its own fleet. In the centuries between, the Channel was no barrier.

During that time, England was invaded by Celts, Romans, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians, Danes, Vikings, Normands, French, Dutch… It has been invaded 73 times just since the Norman invasion in 1066!

As Northern Europe developed and its population grew, all the states that emerged threatened England, since it was the closest and most easily accessible flatland of the British Isles. While these neighboring invasions lasted, London was exposed, as invading boats could reach it from the river. While these threats persisted, locals moved away from the east coast. The capital moved to cities like Winchester or Northampton, both more inland and less vulnerable to the threat from the sea.

This affected not just London, but the entire east and southeast coast, making eastern England a prime target for invasion, pillage, and emigrants.

So this is why eastern England is very fertile yet lightly populated: Historically it was too exposed to invasions from Europe.

It’s also why London took a very long time to grow into the city that it is today.

London Gateway

London would only become the capital of England again after the Norman invasion. This made sense: Until then, the British wanted to get as far away as possible from potential invaders. But the Normans wanted England to be as close as possible to their French territories.

For the Normans, the Channel was not a threat, it was a highway. So when William the Conqueror was crowned, he chose London for the event. A few decades later, the Normans moved the capital there.

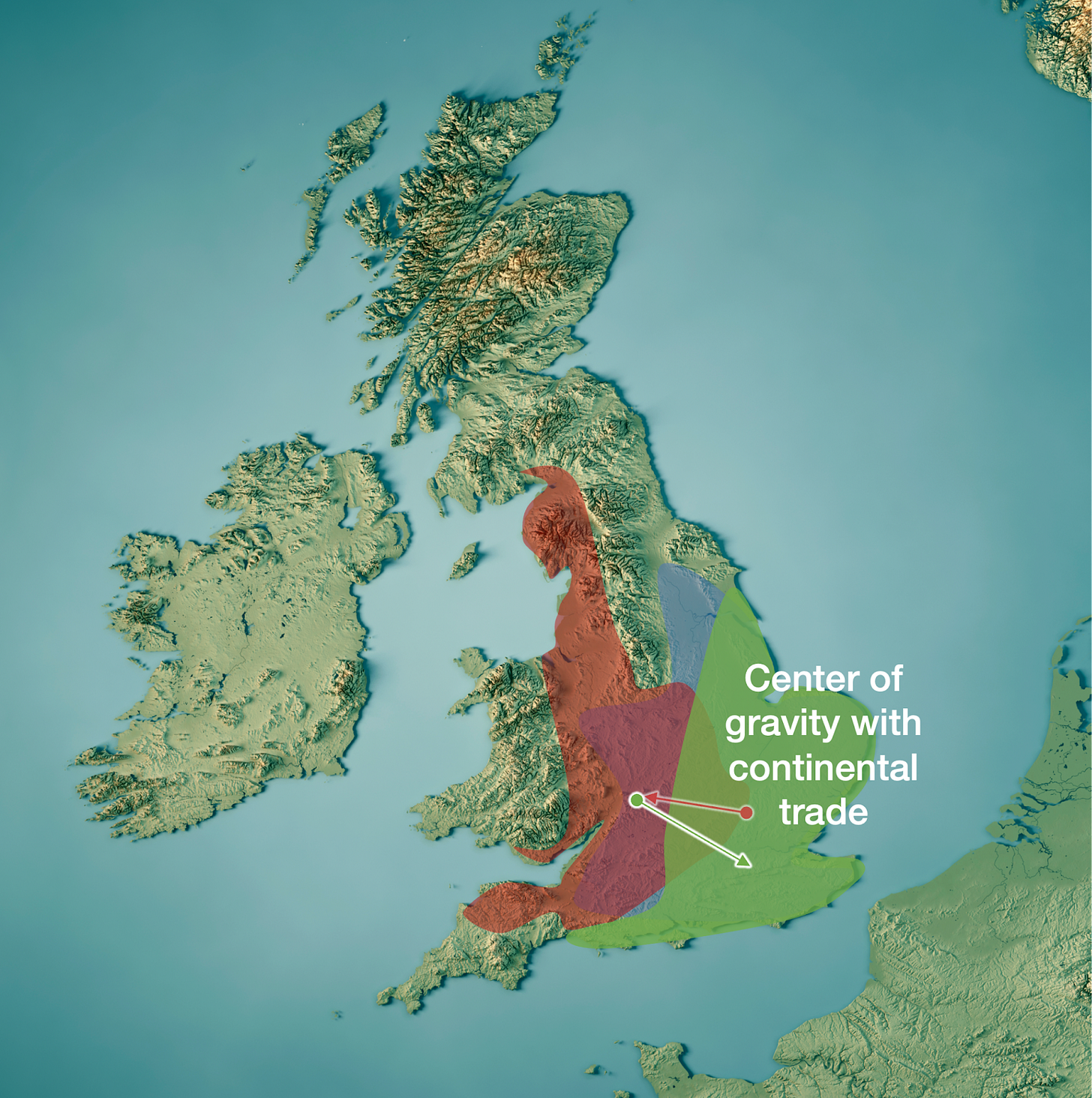

This is interesting: It helps us understand another aspect of geography as one of centers of gravity.

It’s normally in the flat plains of England. But if there’s a massive external threat from the continent:

Conversely, if continental Europe becomes an asset rather than a liability—for example, when Normans owned both sides of the Channel, or when North Sea trade exploded—the natural center of gravity will move back towards the continent.

If this was true, we would only see the population of London start truly growing when trade with the continent expanded. For that to happen, the wars with the continent had to stop, and you needed trade partners to become sizable.

The English had territories in France up to 1557, making wars with the continent inevitable. The Hanseatic League3 grew during the 1200s-1400s, growing the trade with Continental Europe. And the Dutch Golden Age was between 1575 and 1675, a time when trade with the continent was very profitable. So the conditions for trade between the UK and a strong London became optimal sometime between 1550 and 1700.

To give you a sense of the power of London, in 1700 its population was about 500,000. The next largest city in Britain was Bristol, with… 30,000 people! Cities in Northern England were even smaller and poorer.

Another thing happened after England finally gave up its territorial claims on Continental Europe. Spain was filling its coffers with the silver from a new continent, America. Portugal was fabulously rich thanks to the direct path it had found to the Indies. Both were well positioned on the Atlantic. The Netherlands was starting to get in the game. But England was even better positioned than the Netherlands, closer to the Atlantic, and without neighbors that could invade it so easily from the Northern European Plain. Why wouldn’t it participate in the global empire game?

The Colonies

Once the threats outside of the island of Great Britain were eliminated, England was free to focus on the seas.

In the 1500s, England ramped up its sea presence, spied on Portugal and Spain to learn more about their secret colonies, gave licenses to privateers to attack Spanish ships, started colonies in America—the first one was in Newfoundland in 1583—got itself into the slave trade, formed the East India Company in 1600, and the Royal African Company in 1660.

Throughout that time, England kept consolidating the British Isles. Scotland also tried to create its own empire, but failed. The stronger England became, the less it made sense for Scotland to go it alone, and finally in the early 1700s it united with England. Wales and Ireland, both smaller and less populated, had been subjugated over the centuries. Ireland was officially made part of the UK in the 1800s4.

During all this time, the less internal strife there was for the UK, the more it could focus on its colonies. This explosion of Atlantic trade heavily benefited the ports of England’s west coast, with Bristol and Liverpool growing significantly.

Like Spain, France, and the Netherlands, England kept investing in all theaters. Unlike them, it didn’t have to worry about internal strife or continental wars. In that regard, England was more like its ally Portugal, except that with such an amazingly fertile core, its population was much larger than Portugal’s—and hence it had more power.

England got into the triangular trade with Africa and America, which meant it made money by bringing enslaved Africans to America, more money by bringing sugar, tobacco, and cotton to England, and more money by trading finished products—including cloth—to Africa. On top of that, it was able to capture a good chunk of the spice trade from Asia to Europe. In other words, it got itself into all the profitable endeavors of the colonial era, and was successful in all of them.

In summary, the UK—mainly England—was the winner of the colonial wars because it had the most power, because:

England’s fertile lands allowed for a big population.

Over time, England co-opted the less fertile regions of the British Isles, reducing internal strife.

Ending the conflicts with Europe enabled greater focus on the colonies.

All sea travel to the colonies went through the Atlantic, for which the British Isles were well positioned.

England thrived as a maritime power: As an island, it had a natural predisposition for it, and once it had a strong fleet, the Channel became a nearly insurmountable defense.

This defense was extremely valuable as the continental powers lost their focus and spent their riches killing each other.

And it wasn’t done.

The Industrial Revolution

The trends we’ve covered go up to the 1800s. At this point, the newly consolidated UK had been up-and-coming for centuries. At this point, most countries start going down. But the UK had yet another trick up its sleeve.

The Industrial Revolution didn’t suddenly happen in England. For centuries, all of Europe had been increasing its pace of innovation. The printing press eventually led to the Enlightenment, which catalyzed the scientific revolution. The greater freedom in regions like the Netherlands and the UK made them much more innovative.

The Netherlands became the richest country in the world, but got dragged into European wars and lost its hegemony. England, not far from the Netherlands, imported a lot of its technology and furthered innovation. When Europe fell into the Napoleonic wars, every country on the continent was affected, but the UK emerged mostly unscathed.

So England started the 1800s with military dominance, little competition, a huge trade surplus, lots of technology, and the freedom to develop it. That’s when it ran out of wood and people.

4. Specialized Industries

Why are three of the top four cities in the UK not on the coast or on big rivers—Manchester, Birmingham, and Leeds?

To give you a sense of the size of their rivers, this is Birmingham’s Rea River:

None of these cities was on a river, coast, head of navigation… So how did all these cities become so big?

They were all backwaters until the Industrial Revolution.

Up to that point, Manchester specialized in cotton, Leeds in wool, and Birmingham in ironworks5. This region started building canals in the 1700s, which dropped the cost of transportation, increased trade, and attracted people. The trade with the colonies made them very rich.

But all this growth required resources, and England ran out of wood to burn. Coal mining, which existed before, became more important. And most of the coal lay beneath those central mountains.

What changed was, simply, Britain ran out of forests. Thanks to the need for firewood and charcoal for heat, as well as timber for building (especially shipbuilding; Britain's navy consumed a vast quantity of wood in construction and repairs), Britain was forced to import huge quantities of wood from abroad by the end of the seventeenth century. As firewood became prohibitively expensive, British people increasingly turned to coal. Already by the seventeenth century, former prejudices against coal as dirty and distasteful had given way to the necessity of its use as a fuel source for heat. As the Industrial Revolution began in the latter half of the eighteenth century, thanks to a series of key inventions, the vast energy capacity of coal was unleashed for the first time. By 1815, annual British coal production yielded energy equivalent to what could be garnered from burning a hypothetical forest equal in area to all of England, Scotland, and Wales.—Geography of the Industrial Revolution, Christopher Brooks.

Water frequently filtered into the coal mines, so it needed to be pumped out. As coal became more valuable, there was demand to automate the extraction of water to increase the mining productivity. It turns out that the invention to make it happen was nearly available, as engineers had been working on the steam engine for quite a long time. The steam engine found a key use case that enabled the tweaks that would make it work. The need to remove water from coal mines hastened the practical adaptation of the steam engine.

Immediately, other business-focused entrepreneurs saw the potential of the steam engine for their own specialized industries. Manchester, which specialized in cotton, suddenly had:

Cheap cotton from American slavery.

The steam engine to automate transforming cotton into cloth.

The coal to fuel the steam engine.

The canals to ship the resulting product.

The colonies to buy that product.

But you did need the neighboring, independent, free, business-focused entrepreneurs to exist for the Industrial Revolution to take place there.

And this is how the Industrial Revolution emerged in that area6, which crowned the UK as the global superpower of the 1800s.

Takeaways

It’s time to revisit our original questions.

Why Do So Many People Wrongly Confuse England and the UK?

Because England really is the plain of the Island of Britain, and is among the best plains in Europe. That’s why it has 85% of the country’s population and 88% of the country’s wealth.

Why Does It Have Separatist Movements among the Strongest in Europe?

Because it has presence on two islands, the main one is elongated, and has plenty of mountains. Every mountainous area outside of England’s center is separatist.

Why Is Its Relationship with Ireland the Way It Is?

Ireland is to Britain what Britain is to Europe: A smaller island that is close enough to commingle culturally, far enough to create its own identity and nation, and big enough to be a valuable ally and concerning threat. So the same way as the European continent has tried to control Britain, so does Britain try to control Ireland, and both want independence.

Why Did the UK Become a Global Superpower, and Why Did the Industrial Revolution Start in England?

It’s crazy how many elements had to align for the UK to get to that superpower position in the 1800s:

It needed a big, irrigated, fertile plain to grow its population.

An external enemy to unite the rest of the Island of Britain.

Losing its territories in continental Europe, for more focus.

A great position on the Atlantic.

A neighbor—the Netherlands—with a lot of wealth and technology to trade with and learn from.

A political system that was conducive to freedom and innovation.

Continental enemies that killed each other.

A combative nature to spur Europe into rapid technological progress.

A massive gap in technology between Europe and the rest of the world.

A Channel for a strong defense in the Colonial Era.

Triangular trade to make it rich and develop its specialized industries.

A steam engine that had evolved for over a century, to be close to ready.

Cheap and readily available coal to fuel the usage of the steam engine.

Coal mines that filled with water, as a trigger to make the steam engine functional.

Most of these factors are purely geographic: the island, the Channel, the plains, the coal, the wealthy neighbor, the neighbors that killed each other, the external enemy… But not the steam engine. The UK had the perfect conditions to get it to fruition, but maybe in an alternate universe another path to the Industrial Revolution would have been possible, and pursued somewhere else. Alas, we live in this one, and this is how it happened7.

Why is London—a city in a small plain of a small island—one of the biggest megalopolises in the world?

Because the plain was small enough, with one big river whose mouth was close to Europe, that only one big city could emerge. And since the UK became a global superpower, London inherited its importance.

Why Did the UK Brexit from the EU? Will It Ever Return?

There are two kinds of European nations. There are small nations and there are countries that have not yet realized they are small nations.—Danish Finance Minister Kristian Jensen, 2017.

The UK was invaded hundreds of times, always from Continental Europe. It’s logical to pass down some hesitance over the generations.

The UK’s position in Europe allowed it to benefit from the technological and cultural progress of the continent.

Its position on the Atlantic allowed it to take advantage of the discovery age.

The Channel separating it from the European continent provided it enough protection to focus on the ocean, build a navy, and use it to build a global empire.

This level of power is hard to forget. Other countries that lost it much sooner, such as Spain, still haven’t fully internalized it.

This is even truer given the closeness with the US. All of this explains Brexit.

But eventually culture will become more uniform across the Free World.

When that happens, the UK will be culturally as close to the European continent than it is to the American one today. And geographically, it will still be as close to Europe as it is now.

So whether the UK wants it or not, its future is tied to Europe’s. It might take years or generations, but it’s unavoidable—unless technology makes the physical distance meaningless.

The UK Today and in the Future

The loss of the UK's colonies was inevitable. It was always going to drop down the league table of GDP, to a level more in line with its population. Most of its wealth came from a series of incredible circumstances, but it all rested on Europe’s technological advantage compared to the rest of the world, and the quality of England’s land. Over time:

Continental Europe continued its bellicosity until it went up in flames twice, spurred by the ascendance of Germany. The UK couldn’t avoid it.

The US, with a much better geography than England’s, was going to replace it eventually.

The technological gap with the rest of the world narrowed, making wars of conquest and colonization much harder.

The ideas of nationalism spread to the world, making colonies claim their independence.

The UK is moving to the place where it belongs. It is just painful for many to internalize it, and this drives things like Brexit, or the current internal search for a new identity that we see in British politics today, with a succession of governments competing to see which one is the worst, and no vision of a bright future.

However bad the UK’s politics is today, it’s still leaving a decent8 inheritance from its history, like having brought the Industrial Revolution to the world, or the English language that is becoming the world’s Lingua Franca.

No matter what happens in the coming years and decades, if history tells us something, it’s this: The UK will bounce back. Its geography is as good as ever9. It’s still close to the European continent, the Anglo-Saxon community, and the Free World. One day, the British will have internalized the country’s position in the world, and somebody will come to offer a brighter vision of the future to rally the country behind them.

I hope you enjoyed today’s article! In this week’s premium article, The UK’s Unique Monarchy, Language, and Freedom, we’re going to cover:

Why is the UK, one of the most powerful countries in the world, still a monarchy?

Why was it so free so early? Why was the UK’s parliament one of the earliest?

What is the role of great people in history?

What makes English unique as a language?

Built eons ago to keep the Wildlings on the other side of The Wall.

A league of cities in the Baltic and North Seas that emerged as an independent polity in the late Medieval Era.

And only became independent in the 20th century.

All cities, and Birmingham especially, were a bit more diversified than this, I’m simplifying.

Massive oversimplification, but the point of this article is not to explain the industrial revolution, it’s to share the current thinking of why it happened in England first.

In case it’s not clear, let me state it again. When you cover an entire country’s history in a post, you have to simplify. There’s no full consensus on how the Industrial Revolution emerged, but lots of interesting research on the topic is happening now.

Obviously with the corresponding downside and baggage of colonization, slavery, and abuse.

Unless climate change disagrees. On one side, a warmer global climate is good for the cold islands. On the other, given its very flat plains, it might require a lot of investment to keep it above the sea level.

Hi Tomas, well done as always. If you were to add an appendix to your article, it might be the British embrace of learning in general and science/ technology in particular.

Most noblemen and (as the centuries went on) rich young men attended universities, particularly Oxford and Cambridge. The Royal Society gave scientifically-minded people a place to gather, report and rebate. It was also seen as an honor to belong.

The Royal Navy and merchant fleet recognized the value of technology to help them survive the sea and to defeat their rivals.

I suspect that the Church of England together with the puritans and other Protestant churches exerted a net positive on the enterprise, but much of the history I know reports the British morality being honored in the breach. But there is a uniform tendency to report bad news. There is also a tendency of those who rebelled against the British Empire, like my fellow Americans, to slant the story so that it justifies their treason/ freedom fighting.

An interesting map I encountered showed population density at the time of the Norman conquest, and East Anglia was the key centre. https://www.themaparchive.com/product/englands-population-in-1086/