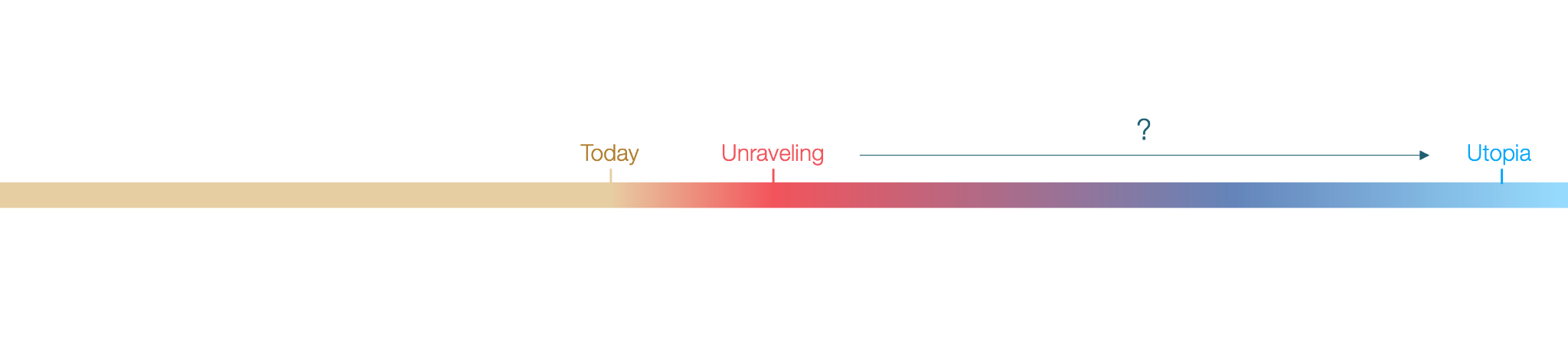

AI: How Do We Avoid Societal Collapse and Build a Utopia?

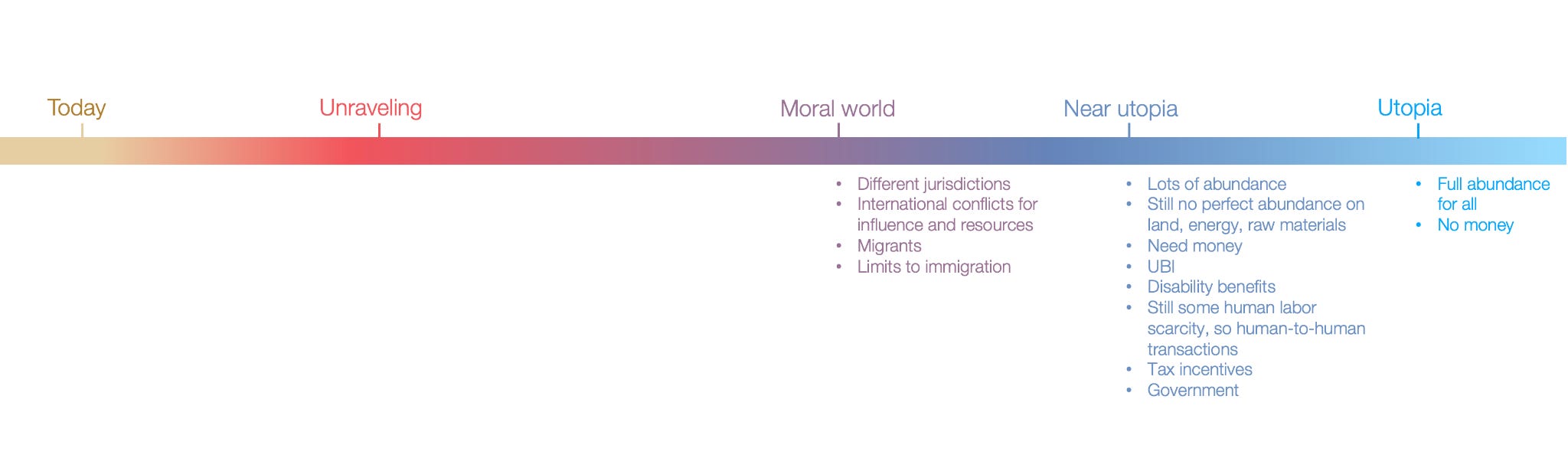

In the previous article, we saw that we’ll eventually live in a utopia, a world of full abundance and without the conflicts over scarce resources that have plagued humanity throughout history.

But on our path to get there, we will face a difficult transition, a social unraveling due to fewer people working while those who do work make millions. This will usher in an inequality that will push taxes up, but the makers will have freedom of movement and will want to avoid taxation. This will lead to social conflict.

How will we get through to the other side? This is what we’re going to answer in this article.

The World Just Before Full Abundance

It’ll help if we fast forward to a world just before full abundance.

In this world, all human work has been automated. Machines are working for us to eliminate the last few scarcities:

Energy: Machines are still building huge fusion reactors and plenty of solar panels in space, beaming energy to Earth.

Land: Machines are reshaping Earth. They are making deserts habitable, reshaping coasts for more beaches, creating new seas, creating new cities underwater, building taller and taller buildings, erecting new polar cities, constructing the first few space habitats. They’re also terraforming Mars.

Raw Materials: Machines are mining deeper and deeper parts of the crust. Spaceships have brought asteroids from the asteroid belt to the Earth’s orbit to harvest them.

Why will these things (land, energy, raw materials) be the last ones to be fully automated? Because it’s harder to move atoms than to move bits. Even a superintelligence will have a hard time making all these things at once, and will have to prioritize them and their downstream applications. For example, if it can access one trillion tons of iron, and a few million tons of rarer minerals, how much of that does it allocate to building more compute vs more energy vs more land?

Also, intelligence will not be infinite until there’s infinite energy and infinite compute, which will also need plenty of raw materials and land. So the scarcity of intelligence might not even be completely eliminated until more of these inputs are sufficiently abundant.

Assuming AIs still serve humans, how will they prioritize? They will need a signal of what matters most to humans. How will humans convey that? Through money.

Money is like a vote. You get to spend it however you want, and that determines where companies put their efforts. If everybody wants a second home at the beach, they will bid them up, prices will go up, and AIs will know to build more coasts. If everybody wants more gold jewelry, it will know to mine for more, or maybe to invest more in energy to transmute other elements into gold. AIs will be able to prioritize more energy for gold transmutation against more machinery production for mining or more machinery for beachmaking.

So it’s very unlikely that we’re going to get rid of capitalism. We need the price signal to convey the optimal allocation of capital.

But in that world, where humans are not working anymore because they’ve been fully automated by AIs more intelligent than themselves, how do you decide how much money each person should have?

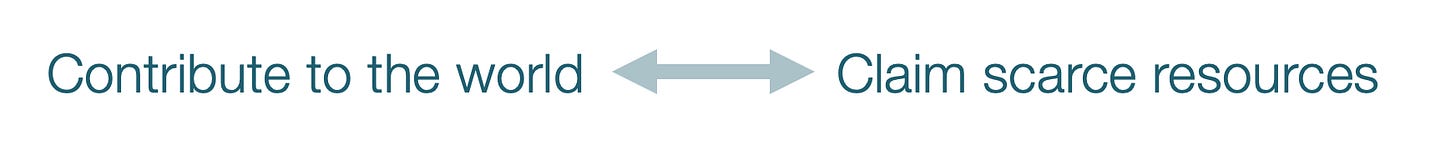

Today, capitalism works because it says: Your claim on scarce resources is equivalent to how much you contribute scarce resources to the world. The more you add, the more you can consume. So if your skills are extremely valuable, you’re going to have a huge salary. For example, if you are an entrepreneur and build something that the entire world covets, you’re going to make a lot of money. If you already have money and you place it in the right places so that your investment is multiplied many times over, you will make more money. That’s the “contribute to the world” part of the sentence. Then, you can have a “claim on scarce resources” with that money: Have more houses, consume more energy, travel more, pay for other humans to serve you (home assistants, coaches, drivers, service employees…).1

Or even simpler:

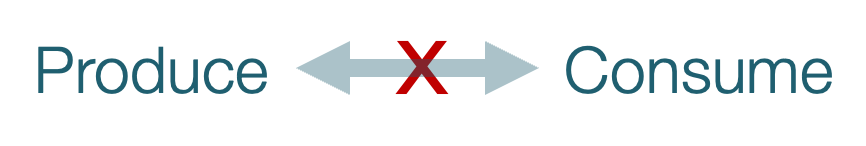

In a world where AIs are much more intelligent than any human (including dexterity, so physical labor is also automated), the “contribute to the world” part doesn’t exist anymore.

So you need another way to distribute scarce resources that is independent from what you can add to the world.

This famous Communist slogan reveals its own naiveté: It’s beautiful, but it disregards that humans are lazy. What motivates most people to contribute to the world is to give them a benefit, so if there’s none, they don’t work.2 And if they can consume endlessly, they will, so the “needs” part just keeps growing.

But in a post-scarcity world, you don’t need to produce anymore, you can just consume. However, you’ll want to consume everything (why not 50 beach houses?) so there must be a limit to your desires. So how can we limit people’s consumption while unshackling it from their production?

With a UBI, a Universal Basic Income: Give everybody the same amount of money (the same claim on scarce resources), because now we don’t need an incentive to work, and every human is fundamentally equal in terms of value.

Imagine that each person gets $10,000 per month as UBI. Food, transportation, energy, and most objects cost near to nothing. Humanoid support robots cost $1,000 apiece. A five-bedroom house in the suburbs of Paris costs $100,000, while an apartment in the middle of Manhattan costs $100,000,000. In other words, with this UBI, you can get nearly everything you want, with the only exception being the stuff that is still scarce.

Where does the money come from? Let’s imagine for now a world government that is coordinated by machines. It takes in what you spend, uses it as a pricing signal to know what to build, and then redistributes that cash in the form of UBI. If need be, it can print money,3 which would cause inflation, but that’s not too problematic, as only the prices of the truly scarce stuff would go up, and the rest not so much. That’s actually what you want.

Now, UBI is not quite according to their needs. Some people have more needs than others—for example, disabled people will need more support. So we might want to correct a UBI with some other income that compensates for this type of need. Let’s call it a disability benefit. For example, an additional $2,000 per month to get more androids to help or whatever.

Also, that world might be one where fertility is through the roof, because the cost of having children and childcare has disappeared, but the emotional benefit is still there. In that case, after enough generations, and before we colonize space, we might want to limit fertility. For example, by only bestowing UBI when children become adults, or by actively penalizing (taxing) childrearing. Conversely, if fertility is too low, we might want to have an incentive to procreate.

Humans Will Still Make Money

Even in that world, however, it’s likely that humans will still transact between each other. Today, we pay more for the imperfect objects made by an artisan. We prefer playing videogames against other humans than against AIs. Although robots are much better drivers than humans, F1 drivers are still humans because we want to admire other humans.

It’s likely that in a future of superintelligences, we might still want to pay for services from other humans: art, artisans, massages, companionship…

People might want to work a little bit, especially if they enjoy their job, to top up their UBI.

OK, so we’ve gone a bit back in time from utopia, and we’ve realized that we still have jobs and we still need to allocate capital, so we still want money and some sort of capitalism, but we also have UBIs that untie production from consumption, enabling a pretty cool utopian world where everybody can live comfortably. We also probably need other incomes for things like disability benefits, and we might need to incentivize or disincentivize some behaviors, like having children. This will require to keep some sort of state and taxation.

Now let’s walk back a bit further.

Social World

Now we’re in a weird world, where superintelligence is here, and for some time it’s been infinitely superior to any human mind, and yet we haven’t been able to solve all scarcity because we don’t agree on what we want in non-economic relationships.

Some people have opinions on what others should be able to do. Should abortion be legal? Should you be able to marry your cousin? Should women wear a veil at all times on the street? Should you be able to insult somebody else? Should we build taller buildings in San Francisco? Should streets have more greenery? More traditional architecture? Should we remove all limits on immigration? Should drugs be legal? Suicide? Euthanasia? What should children learn? Are artificial wombs acceptable? What about human genetic engineering?

Status, control, identity, moral order, fairness, meaning, self-actualization… These are all things that AIs won’t be able to solve with infinite abundance because they’re inherently relational. They rule our interactions with each other, and no amount of physical abundance will solve that, because humans will never be infinitely abundant, and people will always have an opinion on how others should behave.

For many of these questions, different beliefs are incompatible. Sometimes, there is a strictly optimal solution (eg, artificial wombs can solve fertility issues) and hopefully a superintelligence will help us see it. In other cases, there isn’t a solution: What type of street is more beautiful? When does life start (which determines your stance on abortion)?

The only way to solve this is to have different societies live in different places under different rules. Maybe there is some sort of global government (ideally not4), but there will definitely be different jurisdictions.

The moment you have those, you have problems, because each jurisdiction has a different claim on scarce resources. Eg, coasts are more valuable than landlocked areas, some have easier access to good mining resources than others… So polities will fight each other to claim better resources, and potentially to impose their views on others.

And of course, some jurisdictions will force superintelligences to manage things in a suboptimal way. For example, NIMBYs might preempt more housing, which would continue driving prices through the roof in some places, making housing unaffordable.

This, in turn, will cause migration, as some people will want to go from poorly-managed places to better-managed ones, or to places that better represent their values. For example, some areas with more freedom might attract people from stricter jurisdictions. But immigration is very problematic in a world of UBI, because the point of UBI is to give an equal claim on scarce resources to all the people in a jurisdiction. The more you accept people, the smaller the claim is for each. This is not always true today, as in many cases immigrants produce more than they consume. So limits on immigration will have to continue existing, yet unlike today, there won’t be a good reason for accepting migrants.

OK so we’ve reinvented jurisdictions, fights between them, immigration, and limits to it.

Now, we’re ready for the crucial step.

Humans in the Loop

Now let’s go to a world where humans are not quite automated yet, say, 90% of jobs are automated, but we still have 10% of humans toiling alongside the AIs and robots. What does that look like?

Since the majority of the population is unemployed, we need a UBI. But we can’t make do with just that, because then why would the remaining 10% still work?

Let’s make it concrete. Imagine that the remaining jobs are hard things to automate like nurses, electricians, janitors, CEOs, entrepreneurs, and elite computer scientists and designers. There’s a clear distinction between these:

Service people that work physically and locally with their bodies, like nurses or plumbers. Their services aren’t tradeable (they can’t export them) and don’t scale.

Automators: CEOs, entrepreneurs, software developers and designers, who will work on further automating the economy. Their jobs scale immensely and they can work from anywhere.

1. Service Jobs

The service people will be needed and available everywhere in the world. They will be the fundamental jobs for middle classes. The unemployment will be so high that many will try to get into these trades, driving wages down—as long as these wages are much higher than UBI.

So now we have a problem with the UBI amount: Too much, and we don’t get the service workers society needs, because UBI is enough to live comfortably. Too little, and most people starve, because they can’t find a job.

Let’s imagine that UBI is fixed at this point at $1,000 per month. This sounds like it’s not much, but remember that we’re in a world where most services are now automated!

A full lunch might cost $1

A transportation ride might cost $0.01

An android might cost $3,000

An apartment in a low-cost area might cost $200/month

Electricity, phone, and Internet service might cost all together $30/month

$1,000 would be plenty!

So if an electrician makes $10,000 per month, she’ll be rich. Even with $5,000, or $3,000, it could be enough to incentivize people to get into these trades.

Conversely, if UBI is $10,000 and the monthly income of a nurse is $3,000, a couple of things might happen:

This huge UBI would mean people consume a lot, and scarcity would still be hit, bringing prices up.

This would be painful in the short term for all service workers if their income can’t adjust quickly to inflation.

Because $3,000 is not much, people might not think it’s worth it to become a nurse, and there might be a shortage. If their wages depend on the free market, their wages would shoot up until they’re high enough to motivate newcomers.

2. Automators

The mechanics of automators are completely different. If they automate a part of the economy successfully, they can get millions of customers paying them every month, so they can make a fortune from anywhere in the world.

Knowing this, a ton of people will try to automate parts of the economy! The competition will be brutal, and most people will actually not succeed. But those who do will be super rich.

You actually want them to be super rich! Because that’s the siren call to attract others into this market, copy the product, drop prices, and compete benefits away. The more millionaires are minted this way, the more competition appears, accelerating automation for the benefit of all.

To make this tangible, let’s take legal services. Imagine somebody makes a flawless AI that is better than all existing human lawyers. You want that company to be worth billions, and plaster pictures of the amazing entrepreneurs behind it across social media. One entrepreneurial lawyer who has lost her job might see that success and think “I know this tool, it doesn’t work so well in this part of law that I know well, I can do better.” So she partners with a handful of designers and software developers, and together they build a smaller AI that is better in this particular aspect of law. They make millions.

Another ex-lawyer sees this and thinks: “I can do better…”

So the key here is to keep the current mechanisms of compensation intact, to push automation ever further.

Being motivated by making fortunes, you can’t tax their fortunes away though, because they’re mobile and they’re going to go elsewhere to build these AIs. So how do you tax them and how much?

The Role of the Government

The problem we’re facing here is that 10% of the population would sustain the remaining 90%.

Today, the share of the population that works is ~45% in the Western World.5 We’re talking nearly doubling those who don’t produce and dividing the number that produces by 4, to make the system 8x less viable than it is today. Not great.

Just to give you orders of magnitude, I asked Grok what the free cash flow of NVIDIA, Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Broadcom is going to be in 2025, and it estimates $450B, which is $110 per US resident per month. Not enough to live.

And what about regions that don’t even have these companies to tax, like European countries or Japan? They’re also smaller than the US or China, so they have less leverage to compel companies into taxation.

This is why Europe is playing with a tax on consumption of digital services, since Europe is not producing much AI, but it’s consuming lots of it. It’s also why it’s exploring global taxation (taxing European nationals abroad, something the US already does).

This is also why some people have suggested taxing robots: If we tax these things that generate so much abundance, maybe we can pay for human consumption! But this is stupid because:

It’s impossible to enforce: What qualifies as a robot? A humanoid robot? What if it works half as fast as a human? 10x as fast? What if the robot doesn’t look human? What if it’s a big machine that does the work of 10 humans? How would you even know it replaces 10 jobs, when it just makes existing employees more productive? What if it’s a digital agent? Or a series of millions of them, interconnected?

It disincentivizes the very thing that we want! We do want as much automation, as fast as possible, to bring all costs down! If we tax them, we increase their cost, and reduce the return on their investment. We will build fewer of them. They will remain more expensive, and will only replace a few tasks.

What about the automators? They will move to cheaper jurisdictions, many of which are purposefully targeting digital entrepreneurs with low taxes. These include countries like the UAE, Singapore, Estonia, Malta, some Caribbean islands, Special Economic Zones… Some people are already moving, and I expect more to follow.

The main source of capital that can’t move as easily is land. And most developed countries are endowed with great, valuable land. So you can expect that land to be taxed much more heavily than it has been in the past. This would have the benefit that people would try to optimize its value in a way that isn’t done today. I think the cleverest way to achieve this is through Harberger Taxes. Other types of assets that could be similarly taxed include intermodal transportation hubs, factories, and the like.

Another way governments could approach this is with a wealth fund: Take taxes today and invest them into AI companies, using their dividends afterwards to fund UBI. This is a bit like what Norway or Saudi Arabia are doing today. We could give every newborn in a country an endowment invested in all the companies in the stock market, and they could use the proceeds as they please.

The problem I see with this is that “visionary” and “fiscally disciplined” don’t belong in the same sentence as “government”. I don’t foresee any party pushing for this. Yet.

What’s the Most Likely to Happen, Unless We Do Something?

We’re about to enter an even more chaotic time, with awe-inspiring AIs delivering amazing services for a fraction of the current price, while at the same time people lose their jobs, a few automators get rich, and the government in the middle will have to redistribute with something like a UBI, but will be handicapped by automators’ mobility. So what can we do?

I think we’re already on our way to this world, both its problems and its solutions.

In an interview6, Tyler Cowen said something like:

“I used to think that the solution to automation was going to be UBI, but now I’m not so sure. I changed my mind in 2009, when an obvious solution to the problem of the real estate bubble burst was to help those that had bad mortgages. But people hated that. They said: ‘Why would this person, who clearly didn’t manage their money well, benefit from help with their mortgage, and the ownership of a new house, when I managed my money better, but I wouldn’t get that benefit? That’s unfair!’ So we ended up just bailing out big corporations. That led me to think that we people won’t accept a UBI.

So what are we going to get?

Disability benefits. Retirement benefits. Earned income tax credits. Child tax credits. Homeless care. Free education. Free healthcare. In a way, we’re already on the path of UBI, we’re just calling it by different names and making it a bit more complicated.”

I don’t think people will reject UBI. UBI is a very simple thing to sell: Everybody gets the same amount of money every month, no matter what. It’s fair, and it eliminates the biggest downsides in life. You’ll always have a cushion for any fall; you can take risks.

But I think Cowen is spot on in his interpretation that we’re already on our way to UBI under a different name. It’s just less fair and more complicated right now.

So governments need to simplify these entitlements and make them fairer. For example:

Retirement benefits are too high in many countries today.7 They need to go down.

The retirement age must increase: 65 year old people can still produce.8

Free or highly subsidized university and graduate education is unfair. Students should pay for it.9

But another key piece of the puzzle is that all costs need to go down. If some things become dirt cheap while others remain super expensive, the expensive things will become the lion’s share of people’s expenses, and they will feel miserable because they can’t afford them. This is happening today in high-quality healthcare and education, and especially in real estate, across many countries but especially in the US. This won’t fly: If you can afford everything but shelter, you’re still going to be irate. So governments must obsess about reducing the cost of these services.10

This suggests how the world will evolve in the coming years, if an AI superintelligence doesn’t kill us all, and the speed of job destruction is faster than that of job creation:

Every year, we will have more automation.

This will eliminate jobs.

Some people will recycle themselves into the new economy: influencers, AI entrepreneurs, and the like.

Others will change trades.

Governments will increase entitlements, converging towards UBI, in name or in function.

This might come forced by socialist voting, or by visionary leaders who see the writing on the wall.

To fund this, governments will emit debt, print money, and try to tax automators.

This will generate inflation in jurisdictions that can’t easily tax automators.

Automators will move to low-tax jurisdictions to avoid this taxation.

Lots of new millionaires that are uprooted from the land will be minted, living in the jurisdictions that welcome them. There will be more and more jurisdictions competing for them. The ones that emerge now will have an advantage later.

Automator communities will emerge to push for their rights, which include low taxation.

Countries will react by improving their tracking of citizens, inside and outside their countries, to know how much they have and how much they make, and try to tax them even from abroad. Conflict between countries will be intense: They’ll all compete for the same tax dollars.

Countries will be torn between existing populations that don’t produce much but demand UBI or equivalents, and automators who demand low taxes.

Taxation will have to attack automation consumption somehow, less so production.

Governments with strong automator ecosystems like the US or China will have a strong advantage and more stability.

Governments with other benefits (like countries with high standards of living, safe streets, beautiful architecture, strong social life) might also have advantages to attract and tax automators, and will be able to tax their assets, too.

Governments will have to work to lower the cost of the most expensive items, especially real estate, education, and healthcare.

Over time, the more automation kicks in, the cheaper everything is going to be, making everything affordable.

In parallel, UBI (or effectively similar redistribution schemes) will keep growing, until they’re high enough that everybody can live comfortably.

Developed countries will close to immigrants. The more there’s automation, the less valuable new workers are, and the more expensive their entitlements become.

Based on all this, what would I do if I were the leader of a developed nation that is not the US? I’ll discuss this in a premium article tomorrow. After that, in AI, I’ll cover:

How much further can AI algorithms take us? (premium)

The potential blockers to AGI: electricity? Data? Something else? (premium)

The geopolitical ramifications: Who will win, the US or China?

This system doesn’t always work perfectly, and that’s why the field of economics is important, to correct for all the times it goes awry.

The compensation doesn’t need to be monetary. It can be status, simple gratitude from recipients… But they need to get something in return. Monetary compensation is just the simplest, clearest signal, because it’s scalable, impossible to game, includes a clear claim on scarce resources, fungible, scarce, divisible, portable…

I.e., create money from thin air. Press a button and generate more money.

A global government is extremely dangerous, because it has a single point of failure. If it’s taken over by bad actors, the result is infinite misery forever. Better to have different countries that can act as checks and balances on each other.

I think it’s this one where he interviewed Sam Altman. Cowen is so good that sometimes he knows more than his interviewees on some aspects in their fields, so he gets to share insights as interesting as his guests’.

I will write about this. But Spain and France are two examples of ridiculously generous pensions.

If they can’t they should have disability compensation, not retirement.

If Bryan Caplan is right in The Case Against Education that most higher education is signaling. The portion that’s not (eg STEM) can be financed privately, if the return to society is so high. Although I’m more amenable to public financing of this type of education.

Caveat: Real estate costs might drop naturally. But might take too long.

>if an AI superintelligence doesn’t kill us all

This is what I'm most worried about personally. Did you read the "If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies" book? https://ifanyonebuildsit.com/

Once you factor this risk into account, the "as much automation, as fast as possible" logic stops making sense. Faster development increases the probability of issues such as the Grok MechaHitler incident, which we fundamentally have little knowledge of how prevent in a sound and reliable way (trust me, I used to work as a machine learning engineer). The insane thing is just about a week after the MechaHitler incident, the Pentagon signed a $200 million contract with xAI.

I don't understand why people are acting like this is going to turn out OK. It seems to me that we have a few people who are being extraordinarily reckless, and a much larger population of individuals who are sleepwalking.

I remember in the US, people didn't start freaking out about COVID when hospitals were filling up in China. It was only when hospitals started filling in the US that they truly realized what was going on. Most people are remarkably weak in their ability to understand and extrapolate the theoretical basis of a risk. The risk has to punch them in the face before they react. The issue is that for certain risks, you don't get a second chance.

If there's no need to work anymore at some point, it's likely that a lot of people will get stuck in boredom, loneliness and apathy, like many retirees or lottery winners today.

So perhaps one thing we'll pay other humans for will be temporary relief from boredom. Hope it will look more like a comedy channel than a coliseum.