Life used to be punctuated by rites of passage for all the big changes: from birth to coming-of-age, to marriage, death, and many others in between. But they’re now fading away, whether religious ones, like baptisms and big marriage ceremonies, or secular ones, like hazing.

Without these milestones, life becomes a blur. Adults behave like kids, couples like singles, fewer children are born, mental health worsens, social malaise consumes modern minds.

Religion and its rites might be weakening, but we still need the psychology of rites of passage. If we want a healthy life and a healthy society, we must reclaim them. But simply to revive the rites of passage of days past won’t suffice. They are outdated; they have outlived their purpose. We need to create new ones, which requires understanding those of the past.

What was their goal? How did they work? What modern problems can we solve with them? How can we use these insights to create rites of passage for the 21st century? How can we recreate them in our increasingly online world, since rites of passage have always been very sensorial and social experiences, with dance, music, participants, audiences, and symbols?

If we want to bring back rites of passage, we need to start from 1st principles to understand our psychological needs and craft experiences that give them the importance they deserve. Today, we’re going to dive into one specific transition: coming of age. In the premium articles, we’ll explore other key transitions: birth, hazing, marriage, and death.

Coming of Age Around the World

Most religions and cultures celebrate a milestone around 13-16 years of age. Christianity has the Confirmation, Judaism the Bar and Bat Mitzvah, Mexicans the Quinceañera, the Amish the Rumspringa, the Dipo in Ghana…

Why this age?

Sexual Maturity

Women have their first menstruation at around 12 years old. Sexual maturity for men happens around the same age, maybe slightly later.

These events mark the beginning of sexual activity for both sexes. This is the age by which males and females have sex for the first time (cumulative; the previous graphs were not):

So humans become sexually mature around 11-15 years old. It is not a coincidence that coming-of-age rites of passage throughout the world happen around that time. But what’s their purpose?

In some societies, girls who have become women are introduced to society as available for dating and marrying. This is the case of the Quinceañera in Latin American countries.

The same is true of débutante balls.

In some parts of India, the Ritu Kala Samskaram is the first time a girl can wear a half-sari.

In other societies, instead of exposing the sexual availability of women, it’s subdued. The logic is that there’s a huge set of behaviors that have to change when you can reproduce. Childhood play can now have lifelong consequences: play can be arousing, arousal can lead to sex, sex to children, and children to a life of slavery.1

That’s why around the time of first menstruation some Muslim women start wearing the hijab—as we’ve seen, long hair is a sign of fertility, so hiding it encourages chastity2—, while Orthodox Jews start observing the modesty laws—Tzniut—which include hair and body covering, as well as other chastity rules.

In the extreme, some societies perform genital mutilation around that age to increase chastity.

In men, sexual maturation is less obvious,3 so traditional coming-of-age rites of passage are more spread out over the years.

This is also why the vast majority of girls tend to be initiated individually (just after their first menses), whereas boys can be initiated either individually or in groups.

The Romans had the Liberalia, when a phallus was paraded to represent the sexual coming of age of the boys, at 15 or 16 years old.

The phallus represented fertility, both human and agricultural. It was meant to bless the fields.

The coming-of-age rites of passage of some cultures include circumcision, to prove the manly4 ability to withstand pain, and sometimes for misguided health beliefs.5

Mental Maturity

But the passage to adulthood is not just one of sexual maturity, but also mental maturity.

Another major biological change during this period between puberty and young adulthood is in the frontal lobes of the brain, responsible for such functions as self-control, judgment, emotional regulation, organization, and planning. These changes in turn fuel major shifts in adolescents’ physical and cognitive capacities and their social and achievement-related needs.—Source

As children become adults and gain intellectual abilities, they must adopt new duties, contributing to the household and village, helping to bring food to the table and take care of chores.6

That’s why many rites of passage include training and education, like those of the Sioux:

In the old days, as soon as a girl had her first moon, her menses, she would immediately be isolated from the rest of the camp and begin a four-day ceremony where she was taught by other women. So we symbolically set up one camp a year and have the girls come in for four days.—Source.

Some Aboriginal cultures have walkabouts for men:

As a test of his bravery, boys between the ages of 10 and 16 must venture into the scorching Outback for up to six months. Without modern navigation instruments or weaponry, the adolescents must hunt for food, build shelters, and then find their way back home after this temporary exile.—Source.

In fact, these rites of passage focus more on the mental and cultural aspects of coming of age than on the sexual part. Awkwardly, humans become horny before they become intelligent.

Which means that sometimes, humans’ rites of passage to biological and mental maturity either had to be split in two, delivered too early or too late, or adjusted to some middle ground.

These traditional rites of passage might have had good sides and bad sides, but what’s clear is that rites of passage into adulthood today are unsatisfactory:

Coming of Age Today Is Broken

Religious rites like the Christian Confirmation or the Bar Mitzvah don’t prepare kids for adulthood. They are merely religious events.7

Sometimes, religious congregations do design better rites of passage:

In one dramatic initiation event, a faith community awakened their eleven- and twelve-year-old children from their beds on a Saturday night. Community elders accompanied them to a forest, where they sat around a campfire talking about coming of age, and the community’s expectation for their transformation and transition to adulthood. The children began a process of reflection and dialogue and engaged in individual and group problem-solving challenges. At sunrise the initiates and elders returned to their faith community’s house of worship, where their parents and the congregation greeted them, acknowledged the beginning of their transformation to adulthood, and conducted a sunrise worship service.—David G. Blumenkrantz; Kathryn L. Hong (2008). Coming of age and awakening to spiritual consciousness through rites of passage.

Even more sexually-derived rites like Débutante Balls or Quinceañeras8 don’t prepare people for biological maturity. In some cases, the rites are completely devoid of any sexual or maturity undertones—they’re closer to Disney princess balls.

What about gender roles? What about guidelines for interaction between sexes? What about seduction, exploration, forbidden acts, limits? How do people learn about expectations placed on them in forming a household? None of this is discussed, and children instead form a basic understanding in sex education in school, completed in a twisted way through PornHub and their friends’ hot takes on gender studies.

On one side, it makes sense: For centuries, we have had very strong gender roles that shackled us to behaviors we didn’t like. Boys were forced to behave “like boys” and be strong, not cry, not show weakness. Girls had to be girls and wear pretty dresses and keep silent and know their place. Girls couldn’t love girls; boys always had to feel at home in their boy bodies. The entire system needed rethinking—and still does.

On another side, hidden between these outdated scripts, some of these roles are sensible. For example, chivalry makes evolutionary sense. So does a lot of seduction advice. When we avoid discussing sex, teenagers will figure it out on their own, and the result won’t always be pretty.

More importantly, what is the rite of passage into mental adulthood? Pushing kids to face their fears, discuss taboos, and take on adult responsibilities is necessary, but we don’t systematically do it. Confirmation, Bar Mitzvah, and Quicenañera don’t apply at all.

The closest thing we have today to a rite of passage into adulthood is the graduation from high school. It marks the end of an era, with exams, college applications, formal commencement ceremonies9, congratulations from extended family and friends, and it coincides with sexual passage events like senior prom. It continues with a liminal moment – the summer before college – and ends with the parents handing off the new adult to a college, for those who opt into that. There, university classes will demand more of them intellectually, while campus life will educate them sexually.

But of course this has many shortcomings, starting with the fact that most coming of age rites happen in adolescence, between 12 and 16, not at 18. This pushes sexual and mental maturation to 18 years old, way older than we used to.

Also, this experience is very different for most people. Some people will graduate from high school and go to work, but for others graduation is just an intermediary step in the educational trajectory (leading to college). It recognizes the intellectual aspect of it, but the sexual side has little initiation from adults, and comes way too late. And high school graduation effectively postpones the responsibilities of adulthood: The university handles the child’s survival, it prevents actual contributions to society for far too long, and doesn’t teach how to take care of oneself and others, how to contribute to a household, how to manage finances, taxes, food,laundry, an apartment, utilities… That is, unless the student lives alone off campus, which is not the most standard setup.

Adulthood is also learning to interact with others in a mature way, not just as the child of your parents. It’s realizing that others have equal rights and responsibilities. That you need to cooperate in order to succeed. What rites of passage help teenagers internalize that?

Neither the biological nor the intellectual rites of passage into adulthood prepare children for the technological world. If the Church is so adamant about warning against temptation, how does it not help children deal with the technological temptations of doomscrolling, fake news, or cyberbullying? At least it does tackle temptation. How does school, university, or any other rite of passage help kids deal with the biggest challenge of our time?

As a result, adolescents use crutches like psychotherapy.

What if we created a new rite of passage into adulthood for the 21st century? What would it look like? Maybe we can draw some inspiration from other coming-of-age traditions.

Coming of Age in Secular Societies

Germany, Finland, and Iceland have come up with secular coming-of-age ceremonies.

German Jugendweihe ("youth consecration") began in the 19th century, and today 60-70% of youngsters in the eastern states still participate in it at around 13–14 years of age. They study topics like history and multiculturalism, culture and creativity, civil rights and duties, nature and technology, professions and getting a job, as well as lifestyles and human relations.

Finland’s Prometheus Camps were started only in 1989, are politically and religiously non-aligned, host about 1.5% of Finland’s 14-15 year olds, and explore topics like tolerance towards other people, prejudice and discrimination; drugs, alcohol and addiction; society and making a difference in it; the future; world views, ideologies and religions; personal relationships and sexuality; and the environment. Iceland has something similar, but 13% of its youth participates.

I think this is a good start, but it focuses on talking rather than doing or experiencing, it doesn’t give sexuality its due attention10, doesn’t consider survival and independence… What can we learn from ancient coming-of-age rituals? Maybe they have something to add.

The Patterns of Rites

Considering all these examples, experts have identified some patterns of successful rites of passage.

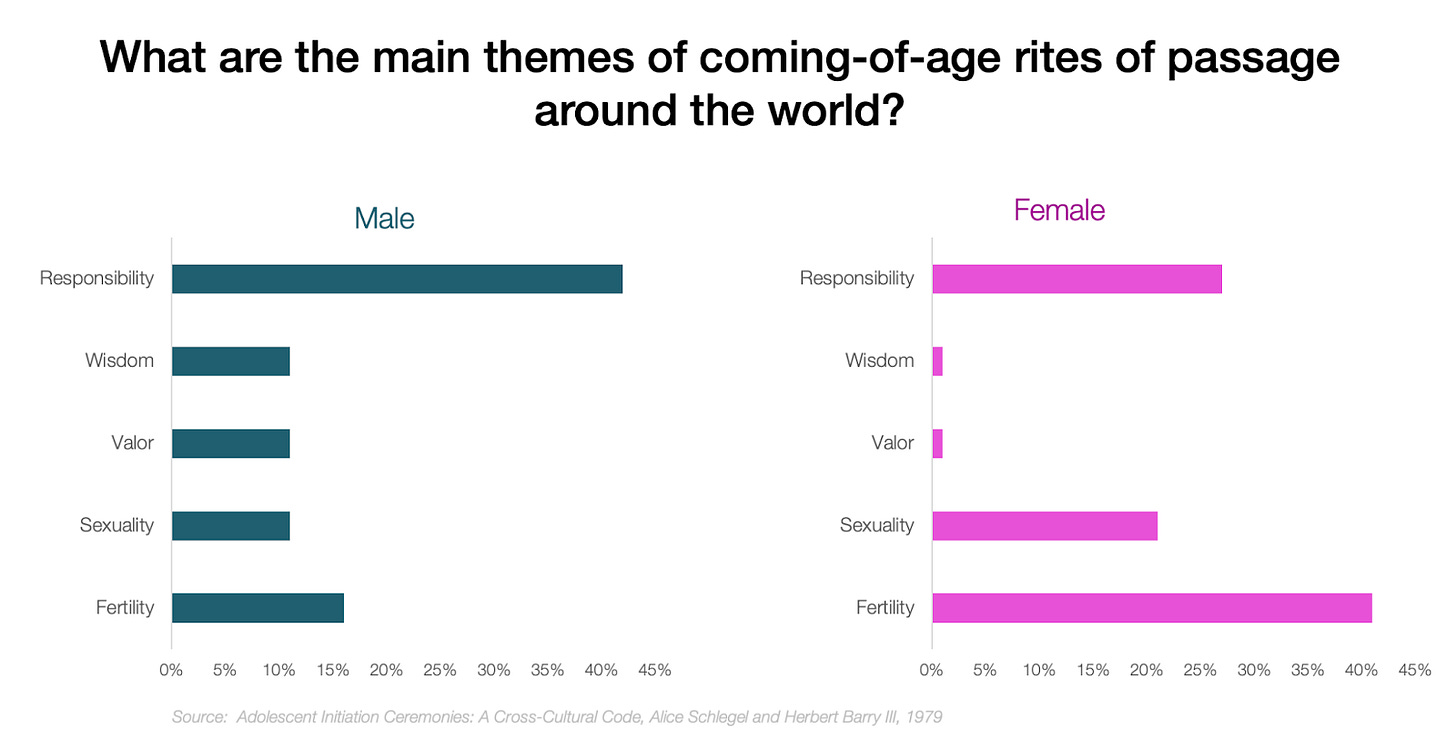

Although sexuality and fertility are major themes (especially among women), responsibility is a huge one, too—especially for men. Wisdom and valor are also strongly highlighted in men.

They also include visible markers of status change, seclusion for reflection, observing taboos for education, pain, fear, and in some cases, sexual acts.

These rites of passage are split into three phases: separation, liminality, and incorporation.

Separation

In the first phase, people are detached from their current status. This usually comes with symbols of cutting away. For example, when joining the military, recruits get their hair cut. They are no longer civilians, with their individuality. They now belong to the army, and are just one of many. Still more symbols reinforce this separation: the number, the uniform, everybody sleeping in the same beds in the same room, lining up with others… Every symbol reinforces the same message: You were a unique individual, now you are indistinguishable from the group. You are cut away from your previous civilian life.

Other cultures, like the Maasai, perform circumcision at that time.

Liminality

Liminality is a fancy word for referring to “a weird, loosely defined phase that you need to traverse in order to go from one place to another”. Here are examples of physical liminal spaces:

In rites of passage, the liminal phase is the period between stages, when the person has left one state but hasn’t reached the new one. It’s the core of the transformational experience, and its nature is necessarily ambiguous.

We talked about the Aboriginal walkabouts before, or the Sioux rite of passage for girls just after their first menses. Here are some more aspects of this rite:

The first thing you need to do is put up your own lodge. During the four days, the girls cannot touch food or drink. They are fed by their mothers and other women in the camp.

“It's treating them like a baby one last time before they become women. No longer would she be my little girl to feed anymore. You really begin to start the foundation of what that adult relationship is with a mother and daughter.”—Source.

In the Amazonian Tukuna:

In order for a woman to pass womanhood, she is left out in tents for days and painted 3 times a day while half-naked, leaving them exposed to the demon “Noo.” If they get through the ritual, they will become full-fledged women.

Here’s an example of pain:

Reincorporation

After the ordeals of the separation and liminality comes the ritual to reincorporate into society, as a different person. Reincorporation is characterized by elaborate rituals and ceremonies, like débutante balls and high school graduation, and by outward symbols of new ties like sacred cords, knots, belts, rings, bracelets, crowns…

The function of the reincorporation is to close the process of passage and recognize the child’s new identity as an adult, a whole part of adult society. This new identity comes with requirements of industry—the new responsibilities of the adult. Finally, it needs to mark the shift from intimacy with the family to intimacy with other individuals. In other words, the child has abandoned the family to join society. By making it a public event, everybody agrees to this covenant.

These three steps of separation, liminality, and reincorporation can be split into more detail. For example:

Here’s an entire cycle for the Dipo of Ghana:

In Ghana, the Krobo group introduces women to adulthood with the two-day Dipo ceremony. Young women, all virgins, get paraded around the community as Dipo-yi, or initiates. They are given a ritual bath, eat sugar cane, drink a cocktail (made of millet beer, palm wine, and schnapps), and their feet are "washed" with slaughtered goats' blood. After these practices, the women leave their village to live in confinement for a week where they are taught about childbirth, cooking, housekeeping, and what they consider being a good wife. They then return to the community and perform the "klama" dance half-clothed and adorned with beads and body paint.

In the Wakamba of East Africa, after an initial ceremony with genital mutilation, the Great Initiation begins, where the adolescents are isolated for educational rituals through which they are taught:

Tribal secrets, sexual roles, and the rights and responsibilities of adulthood. It lasts for three days, and includes songs and stories, mock attacks and raids, mythical creatures, and a sacred ceremony at the Tree of Life. The spirits of the ancestors are invoked. Sexual learnings include physical attention to the genitals, including small cuts, and physical exploration. Ritual intercourse by parents and by adult sponsors is also part of the celebration. Finally, there is feasting, with song and dance.—Dunham, R. M.; Kidwell, J. S.; Wilson, S. M. (1986). Rites of Passage at Adolescence: A Ritual Process Paradigm.

Why do these rites work to help kids become adults?

They physically separate the adolescent from their parents, with a ceremony that gives weight to this event. They emerge from that as independent individuals.

They make adolescents face a challenge that they’re not prepared to overcome, to feel fear and awaken the desire to learn from adult society.

They learn skills and secrets from adults in this time of need, which increases their allegiance to society, and creates a strong group identity.

They push the adolescent to become self-sufficient, increasing their autonomy and mastery.

They explore new roles they might take on as adults.

They explore their sexuality, and learn about traditional (and maybe non-traditional?) gender roles.

They help learn how to plan, because the challenge requires them to think about their needs and fulfill them systematically, not just once, but for the duration of the rite.

How can we translate this type of insight into a 21st century rite of passage into adulthood?

A 21st Century Rite of Passage into Adulthood

One of the biggest challenges for children today when they move into adulthood is their exposure to the unsupervised Internet as individuals—through their smartphone. It is the wilderness of today, the medium in which adults need to survive to thrive. Yet we give away smartphones like they’re nothing, when in fact the relationship with kids will never be the same afterwards. Should we craft rites of passage around that?

Imagine, for example, that every teenager got their first smartphone at 15, but instead of an off-hand event, it was momentous: an earned reward that symbolizes the entrance into the dangerous world of adulthood.

How would teenagers earn their smartphone?

What about a survival trip? Instead of talking about all these topics in a classroom, they could cover them over a couple of weeks in nature, where they would need to source their own food and water, set up their own camp, protect themselves.

This would start with a ceremony where maybe the mother prepares a backpack for the adolescent, and the rest of the community provides things he will need in nature. The mother would give the bag to the child and kiss him goodbye, before the kid heads into nature.

Maybe they could do that with a small group of peers and one guide, whose responsibility is to guide the conversations, teach teenagers how to survive, facilitate conversations, help students meditate to be present in the moment, teach them about the dangers of social media, about finances, about sex. Maybe he could leave them after the first week, so they learn to be truly independent, or the opposite: Come after a few days to help them survive. Maybe the goal of the trip would be to reach a distant point in nature, and success would only be achieved if all the students arrive together and vouch for each other, forcing them to cooperate.

And maybe the reward is a ceremony where they are accepted by other adults, and where they receive a smartphone to signify the dangerous entrance into adulthood.

Maybe after the nature trip, kids would need to go on a backpacking trip through distant countries. They would have to find their own hotels, manage their own budget, buy their own food, talk with lots of people alone, negotiate with other kids where to go and what to do. This would be the justification for the smartphone, as the key tool to navigate the world.

Maybe when they come back, the reincorporation ceremony includes unlocking the social networking features of the smartphone—once they’ve learned to approach people in real life.

I’m not saying this is exactly what we should do, but it’s the type of thing we should be thinking about but aren’t. What do you think a rite of passage into adulthood should look like?

This is a joke.

This is an explanation, not a justification. I prefer a life where women are free to do what they want with their hair and men learn to control their impulses.

But proxies can be used, such as facial or pubic hair, the size of sexual organs, the voice…

Although I’m going to venture that genital mutilation is more painful in the more nerve-filled clitoris than the foreskin.

The practice of circumcision is barbaric to me. It’s very unlikely that it’s good for health, as men would not have evolved foreskin otherwise. A lot of the literature I’ve seen on the topic is very biased. Maybe one day I’ll look into it for a more informed opinion.

Generally in gendered tasks around the world.

And some are not even as traditional as one might think. For example, the Confirmation was initially mixed with Baptism, then split, mixed with the communion, then split…

I assume the Quinceañera is the closest to a sexual rite of passage, as at least it presents the girl as a woman.

Which comes from the French “commencer”, which means beginning. Paradoxically, the word signals that this is not the end of the school period, but the beginning of the next one.

Since sexual and intellectual are the two passages into adulthood in the teenage years, they probably each deserve half of the effort?

I went to a summer camp starting when I was 10, was a camper for a few summers, then did 2 different leadership programs when I was 15 and 16, and then worked as a counsellor for 3 summers when I was 17-19, leading kids on trips into the wild. Reading this article, I realised what a rite of passage the leadership programs - especially the first one - were. When we were campers, the counsellors did the navigation and made the decisions and were otherwise in charge, but during the leadership programs we had 2 “leaders of the day” who were responsible for navigation, planning breaks and otherwise making decisions; the counsellors of the leadership programs were there for safety and to veto bad decisions, but otherwise were hands off. It was a real change from being a camper, and we made lots of mistakes, but we learned from them.

The camp was a community: if you attended a few years in a row, you could see campers become leadership participants and eventually, counsellors. You were curious and excited/nervous to go through the process yourself. For years, I knew how much these experiences had helped me grow as a person and a leader, but this is the first time I’ve considered how it made me grow as a member of a community. Thank you!

If you are looking for a 'singular event,' obtaining a driver's license used to be the modern rite. A smartphone probably should be it nowadays, but it isn't treated as such by a large proportion of society and I think that is probably part of the problem.

Also, this skews younger. Consider: you can never do heroin legally, can't legally drink until you are 21 (past adulthood), can't sign off on legal documents until 18, can't drive until 15/16, can't get a google account until 13... but you can get a smartphone whenever. I suppose in a world where the internet is regulated, a smartphone is not as dangerous as the other things on that list... but in an open internet world, I agree it is arguably the most dangerous of all.

The above paragraph argues that 'rite of passage' is outdated and 'journey of passage' is more accurate, but expanding on that point takes a much longer post.