How Ice Sculpted Canada

This is the 3rd article of the Canada series:

The first one focused on Canada’s weird population patterns (free)

The second one covered its main geopolitical challenge: facing the US (free)

This one (free) and the next (premium) focus on Canada’s north: How ice has shaped its past and will continue shaping its future

The following articles will be about the internal challenges of Canada:

French Canada: Why it’s French, why no other part of North America is, and whether it will ever be independent (paywalled)

Alberta’s drive for independence (premium)

Subscribe to get them if you haven’t yet!

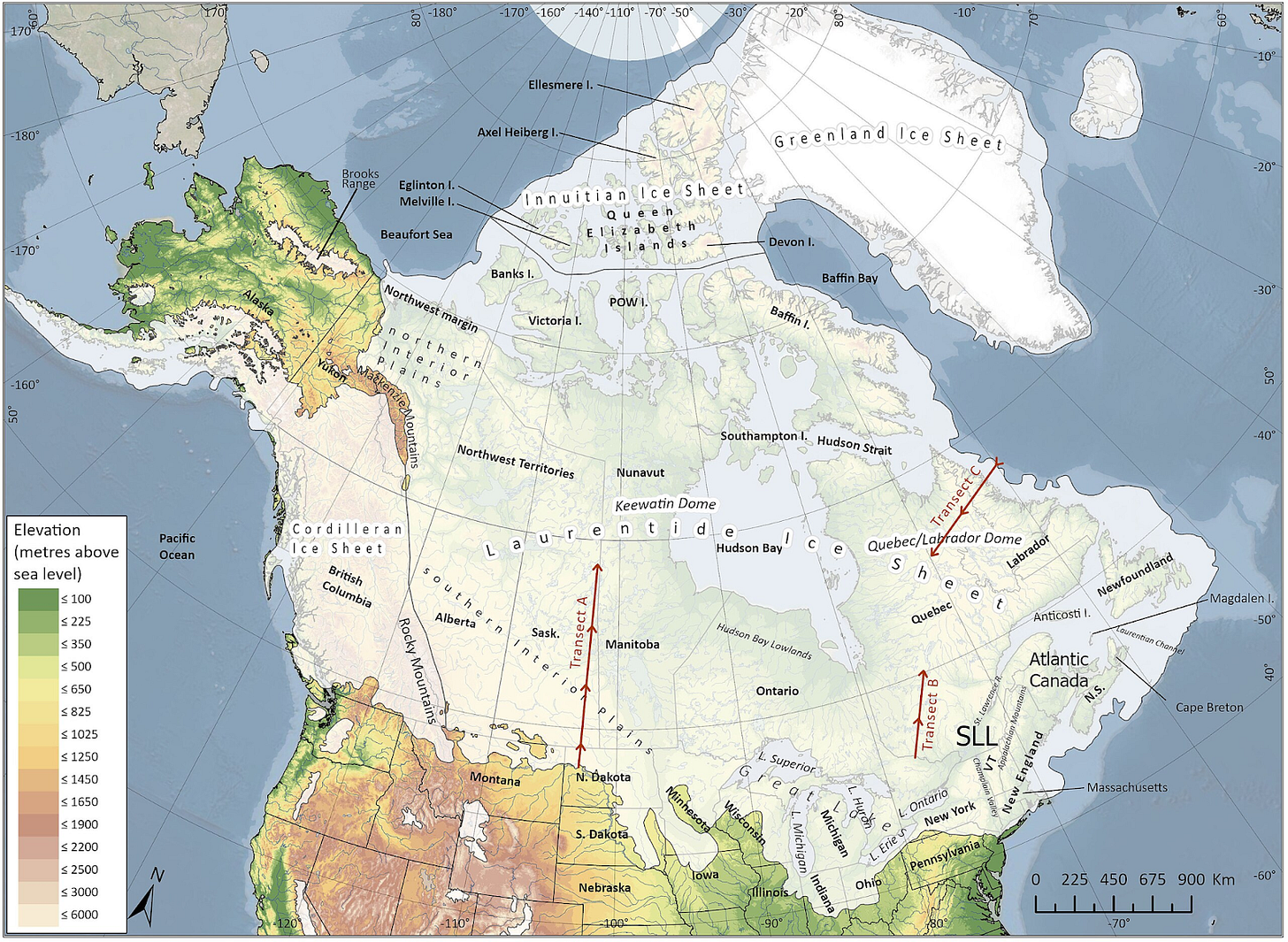

If we’re going to focus on Canada’s ice, we need to look here:

And this area is really big.

1. How Big Is Canada?

You might know that Canada is the 2nd biggest country in the world, but it’s hard to fathom how huge and far north it is.

You probably know that Canada’s south is pretty far north. Even Toronto, one of the warmest Canadian cities, close to the country’s southern border, is very cold.

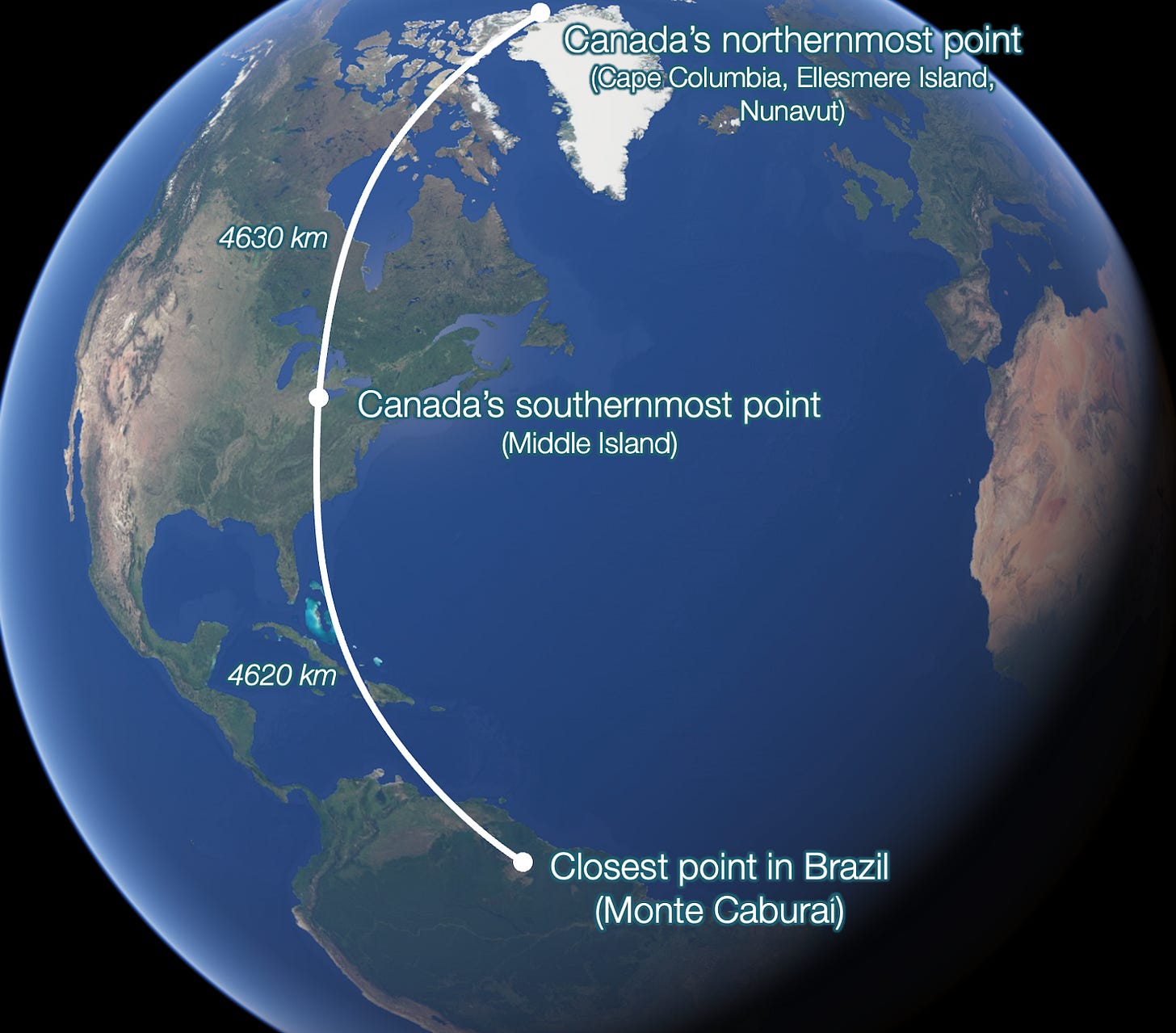

Well, here’s a crazy fact: Did you know that Canada’s southernmost point is nearer to Brazil than to its northernmost point?!

And this vast expanse of ice is also extremely wide. Did you know that its easternmost point is nearer to Europe than to its westernmost point?!

This cold expanse is so big we don’t usually know what goes on in its most remote places…

2. What Goes On in the Far North?

This is mostly the region of Nunavut.

There are barely any trees here.

It’s mostly bare mountains, water, ice, and tundra.

Landscapes seem incredible.

This redditor went there and shared this:

I had the opportunity to go canoeing here last summer (the "Barrenlands" in the northern mainland portion of Nunavut) and I can say it was an absolutely wild and desolate place. It was the height of summer, so the weather was very pleasant, the sun dips below the horizon for a few hours in the middle of the night, but it never got dark. We swam in the river everyday. Lots of wildlife (moose, caribou, grizzlies, wolves, muskox) and great fishing. No trees, just endless rolling green spongey mosses/shrubs and rock stretching to the empty horizon. Hordes of mosquitoes on the non-breezy days. Definitely the most remote and removed locale I have ever traveled to, we didn't see any other humans for 3 weeks along a 300km stretch of river!

But not all the Canadian North is like this. If you go south or east, you might see more taiga, like in this picture of Yukon:

Even in the Canadian Shield, like in southern Ontario:

All in all, this looks fantastic for movies, camping, and adventure trips.

It begs the question though: Why are these the landscapes?

3. Why Is There a Line of Lakes Across the Country?

We don’t realize it, but the Great Lakes are an extension of a line of many lakes, including Great Bear Lake, Great Slave Lake, Lake Athabasca, and others.

When you zoom in, you can see something else that’s interesting:

Notice it’s not quite an issue of rain. There’s very little rain in the region of the northern lakes:

You might recognize, however, from the last couple of articles that the white line of big lakes is broadly the limit of the Canadian Shield:

The lakes are between this shield and the coastal ranges, caused by the Pacific Plate hitting the North American Plate:1

You can see that this area, so close to the coastal mountains, lies lower than the rest of the shield. This is common around very tall mountain ranges: Their weight depresses the land around them. They are called foreland basins:

But in these other places in the world, these depressions have formed river valleys (Paraná, Mesopotamia, Indus, Ganges). Why lakes in Canada? Because of glaciations!

In the valleys of the Paraná, Tigris, Euphrates, Indus, and Ganges, all the rain from the mountains flows downstream, carrying sediments that accumulate over time, filling any hole. If there’s a shallow sea, they will fill it continuously, the way the Tigris & Euphrates fill the Persian Gulf, and the Ganges fills the Bay of Bengal.

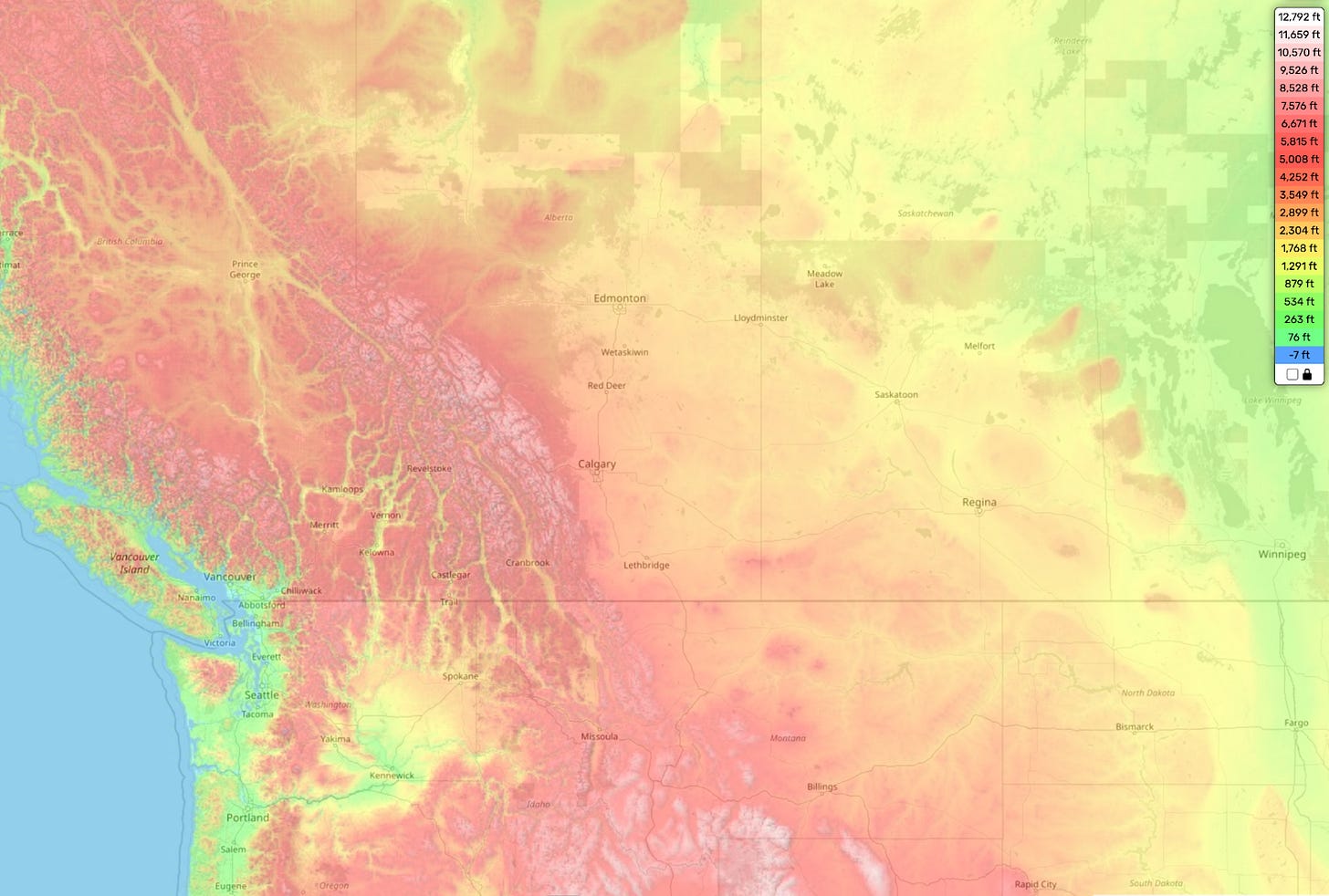

This happened on the Rockies side: You can see that there’s a gentle slope from the Rockies towards the Prairies:

But this transition doesn’t happen on the Canadian Shield. Look at these parts of Finland, Russia, and Canada:

They all have thousands of lakes. Why? Because:

In the far north, it rains less. There is less water to carry sediments.

The ice sheets, with their weight, their movement, and the abrasive ice and stones they carry, dig deep holes in the ground.

They also strip the sediments away, leaving the soil bare, which tends to produce hills and valleys.

The stripped land is more hermetic. Water doesn’t drain, it stays there and ponds.

The sediments carried by glaciers accumulate in some places, forming natural dams.

Sometimes, big pieces of ice can get buried. When this ice later melts, the area collapses, forming another hole for lakes.

The ice pushes the mantle down. When it melts, the land bounces back unevenly, forming peaks and valleys.

This is why Canada hosts a whopping 60% of all of the world’s lakes!2

So why did the lakes accumulate in this precise line then?

On the west side, we have mountains that cause a depression (because mountains are heavy), which is slowly filled with sediments. The lowest part is the one farthest from the mountain ranges—the limit between the sedimentary basin and the Canadian Shield.

On the east side, we have the Canadian Shield, which was heavily weathered by the ice sheets. This weathering was maximal at the edge of the Shield, because this part was lowest, so glaciers would rush there faster and grind them more.

Glaciers left behind more ground-up materials when they receded, forming natural dams. These filled with water, forming vast lakes.

They’re in a line because old cratons tend to have lines and smooth edges.

And how has this geography influenced Canada’s history? Tremendously. Here are two examples.

4. The Ice Company that Changed Canada

This is a map of North America in 1700:

Notice Rupert’s Land, at the top, around Hudson Bay. What’s that? Why is it disconnected from other British colonies? Why is there native land between the two?

It’s because this land didn’t really belong to the British Crown. It was controlled by a company—the Hudson Bay Company. Its control was so thorough that it had its own paper money, courts, governor, force... And its land was not just the Hudson Bay’s shores, but the entire Hudson Bay drainage basin.

In 1670, the British Crown granted the Hudson Bay Company a monopoly for the exploitation of the entire watershed of the Hudson Bay. This basin is as big as the EU! And what did they trade? Beaver furs.

Beavers are adapted to live in cold water, so their furs are very warm and waterproof, and also supple enough to be worked into different shapes—like coats and hats.

So trappers could make a lot of money by hunting beavers and selling their furs in Europe. But beavers live in rivers, so trappers had to follow the rivers. The French did the same thing in the St Lawrence River Valley, by the way.

Since this region was so remote, so cold, and didn’t allow for agriculture, it couldn’t host a big population, so Hudson Bay Company (HBC) trappers relied on alliances with natives to source their furs.

This trade was so profitable that it sparked wars that lasted nearly a century! The Beaver Wars, which started around 1610 and ended around 1700, pitted the Iroquois (supported by the British and Dutch) against the French and their allies (Alongquins, Hurons…). The Native Americans sold the beavers in exchange for Western items, notably guns. Thus, the more beavers they sold, the more guns they got, fueling the war. But the more beavers they sold, the more they drove the beaver population towards extinction, pushing trappers westward to access more beavers.

This happened across North America, including in the north with the Hudson Bay Company: The more time passed, the more beavers it caught, the scarcer they became, and the more the HBC had to travel westward for furs. Eventually, in the 1820s, as it pushed west for more furs, the British Crown was tempted to grant more westward territory to the HBC. The eventual trigger was the fact that the US was also pushing westward to gain more territory. The British granted a monopoly on all lands up to the Pacific Coast to the HBC.

Eventually, in the 19th Century, the British Crown absorbed the HBC’s lands and granted them to Canada, making it the country we know today.3 So Canada’s expansion westward was secured by trapper pioneers in the quest for furs—furs valuable because of the ice they protected against. Economics preceded politics, and geography preceded economics.

It is not the only time the fur trade determined the fate of Canada!

5. How Did Canada End Up Without This Coast?

Half of Canada’s Pacific coast actually belongs to the US! It’s a pretty pitiful coast, and they don’t even own half of it!

How did the US end up doing a Croatia on Canada?

Here’s a world map in 1860:

Notice that Alaska is part of Russia. And it includes that same piece of coast! Why?

In the late 1700s, Russia had been on a mission of imperial conquest for 600 years. One of the main reasons is because of ice, which makes Siberia inhospitable, so it was relatively easy for Russia to keep moving eastward until it reached the end of Asia. And then, like the paleolithic people who crossed the Bering Strait during the last glaciation, Russia jumped the strait and continued its conquest, into present day Alaska.

But if you own Alaska in the 1800s, you don’t really own anything. It’s a bunch of mountains and snow. What can you get from there?

We’re back to furs! Useful because animals make them to protect from the cold!

In this part of the world, snow and mountains make it virtually impossible to go inland, so the only economic value in the 1800s was on the coast: fishing and furs. Russians went as far south as they could, until they faced opposition from the Spanish and the British. The region they occupied ended up in the hands of the US when it bought Alaska from Russia in 1867.

Why did the Russians sell Alaska to the US? Because the land was too far away, and expansionist Americans and British were about to take it over anyway. They decided to sell it to the US because it was the weaker country and Russia’s bigger enemy at the time was the UK—a European competitor and the most powerful country at that time.

The Pacific coastal border and the expansion through the Hudson Bay Company are not the only ways ice has sculpted Canada’s history, of course. But they beg a question: How will ice shape Canada’s future? Or rather, how will its thawing? Will it open up marvelous new economic opportunities for Canada? Will it turn it into a world superpower? This is what I’ll explore in the next article.

Above 0.1 km2 in size

The Hudson Bay Company is the oldest company in North America, and it just declared bankruptcy a few weeks ago.

Loved this piece! Can't resist a couple of comments. 1) "Economics preceded politics, and geography preceded economics." This sentence beautifully sums up pretty much most of your recent work. 2) Thanks for the phrase 'foreland basin', new to me. 3) Hudson's Bay Company: the second oldest company in the world, and the last great near-sovereign corporation of the colonial age, filed for bankruptcy about five weeks ago. Somebody will buy the name, but 355 years in business ends this year. A department store, but it was in the fur business right up to 1991. 4) Finally: at the risk of being a pedant: there's a typo in the word for the language group Algonquian (or Algonquin, for the peoples). The other peoples you mention now prefer their original names rather than the colonial ones, but no matter. Thanks.

The Russians actually got much further south! Fort Ross was a Russian settlement on the Sonoma coast north of San Francisco near the town of Jenner. It was a fur trading post (active from 1812-1842) and is now a California State Historic Site. It was the southernmost Russian settlement in America. The river that flows into the Pacific near Jenner is the Russian River.