Canada vs the 51st State

How can Canada fight against an aggressive US?

Last week Canada held its elections. These were the probabilities of winning for Liberals and Conservatives as of the end of January 2025:

Then this happened:

In the end, the Liberals won. Poilièvre, the Conservative leader, even lost his seat in parliament!

What caused this earthquake?

Trump imposed heavy tariffs on Canada and said it should become the 51st US state. He claims Canada would cease to exist if it weren’t for the US.

The Americans want to break us so they can own us.—Mark Carney, Canadian Prime Minister, April 24th 2025

Is there any truth to Trump’s rhetoric? What should Canada do about it?

1. Canada’s Biggest Threat

The maps we’re used to seeing of Canada don’t fully explain the country. Here’s a better angle:

This makes a few things very obvious:

It’s the 2nd biggest country in the world, and so far north that it’s really cold. This is similar to the biggest country in the world—Russia. This means it has similar challenges: It’s half empty and well protected to its north.

To the west, there’s a huge ocean protecting it.

To the northwest, there’s Russia, but before that we find Alaska. So any threat coming from Russia would first face the wrath of the US.

To the east, there’s another ocean and then the massive and frozen Greenland. Yet another shield.

To the south, it has a border thousands of miles long with the most powerful country in the world.

And as we discussed last time, about 80% of Canada’s population is within 100 miles of the US border.

In other words, this is Canada:

Canada’s first, second, and third priority is its relationship with the US. Until recently, Canada could live with its peaceful relationship with its southern neighbor and the world order it upheld. But the rise of populism around the world is challenging that, with Russia invading Ukraine, China thinking of doing the same with Taiwan, and now Trump’s ideas.

a. Military Threat

Unfortunately, force underpins everything, and Canada is weak compared to the US. The first problem is population.

The US has 8x more people than Canada. It’s also 13x richer. US spending on the military is 35x Canada’s. The problem is not just the numbers, but how disconnected Canada’s centers of population are to each other.

From a military standpoint, Canada is extremely exposed to the US:

In a war, Canada would immediately lose Vancouver, given all the military bases the US holds across the border in Seattle–Tacoma, and the fact that Vancouver is completely isolated from the rest of Canada by the Rockies.

The US would also immediately go for the cities in the Palliser Triangle: Calgary is 150 miles from the border and Winnipeg 70 miles. Edmonton might be a bit harder to take, 300 miles from the border, but the US military has conquered places thousands of miles away from home, so I guess 300 miles of flat prairie doesn’t sound like a hard challenge. Canadian forces could retreat further north, but they would quickly run out of food and oil.

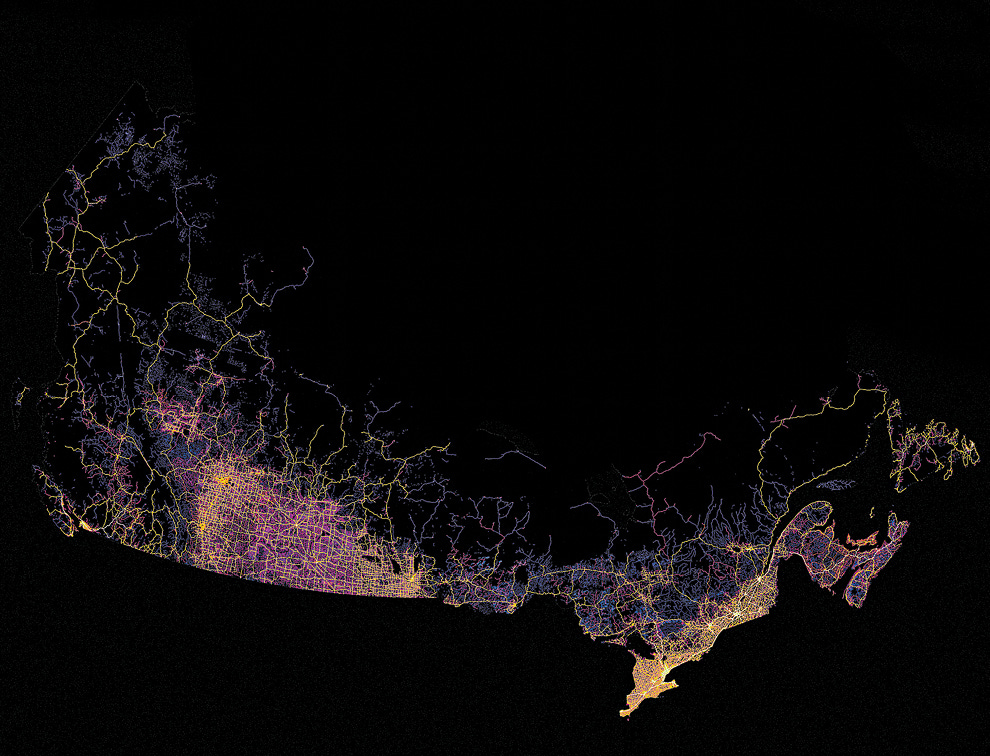

Indeed, the Palliser Triangle has most of Canada’s oil and gas, so losing that region would mean Canada losing its biggest source of income. And it would be easy to disconnect this region from Canada’s heart in the southeast: This is a map of Canada’s major highways and roads.

This would leave the thin strip of inhabited land to the southeast, but that region is very close to the US, and there are several points that the US could use to invade it. And like with the Palliser Triangle, hiding further north would not be an adventure that lasts long.

Compare this with Russia and Ukraine:

Ukraine has 26% of Russia’s population, not 12% like Canada vs the US.

Most of Ukraine is fertile and produces wheat, so it won’t run out of food if only one part is invaded.

It’s very compact, so forces can withdraw towards the center if the edges are conquered—as it has done.

On its western side, it has mostly allies that can support it.

So where Ukraine can stand its ground against Russia, Canada hardly could against the US.

Another comparison is Russia itself: It’s been invaded many times in its history, but nobody has fully conquered it since it became the biggest country on Earth. That’s because of its defense in depth: Napoleon could reach Moscow and burn it, and Hitler could get close, but Russians could always withdraw farther east, burning everything behind them, leaving the invaders with impossibly long distances to cover logistically. This is because Russia has its population spread across its entire length from west to east, and its main foes are at the ends of this extension. For Canada, the threat crosses its whole extent.

It doesn’t mean the US will invade Canada. It means it could, and it would probably win. And both the US and Canada know this.

b. Economic Threat

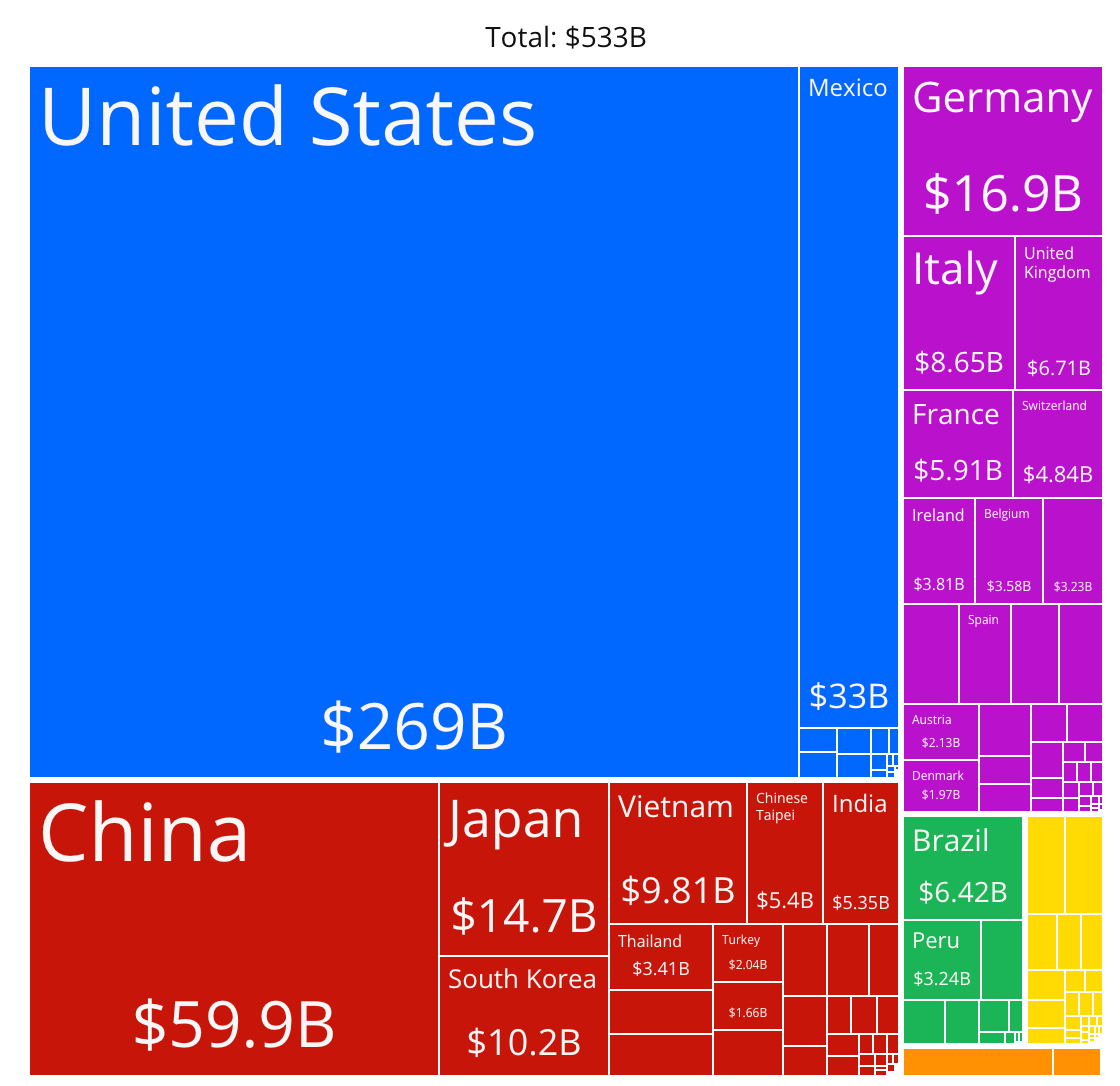

They also know that it wouldn’t even take an invasion for Canada to fold. These are Canada’s exports:

And these are its imports:

The opposite is not true. Canada represents only 14% of US’s imports and exports.

So the US could simply decide to cut 50% of Canada’s needs and ~75% of the money it makes abroad, without losing too much itself. Plus, the US could simply blockade Canada for the rest of imports and exports to be shut down.

Canada is self-sustaining for oil and food, so the society could survive a blockade, but its economy would be utterly destroyed.

If you think about it, this is kind of what Trump is threatening with his tariffs. By making imports and exports so much more expensive, he limits both, putting heavy pressure on Canada’s economy.

Until 2022, a full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia was simply inconceivable. Then Putin did it. Things seem impossible until they aren’t—it only takes the right person in power. Trump and the US are not about to invade Canada. But they could blockade it. And somebody else could come along and do something crazier.

A good Canadian statesman would see all this and think: “Hope for the best, prepare for the worst. We need to be on the US’s good side. But we can’t just hope for it to be nice to us like it’s been in the past. We must prepare for a world in which it’s hostile to us. How do we reduce our dependence on the US, in terms of population and the economy?”

My guess is the answer to this is that Canada needs:

More power, which comes from people and money. So Canada needs to

Increase its population

Accelerate economic growth

To connect its existing regions; right now they’re too disconnected and hence weak

To settle new parts of the country

Let’s explore these.

2. Immigration

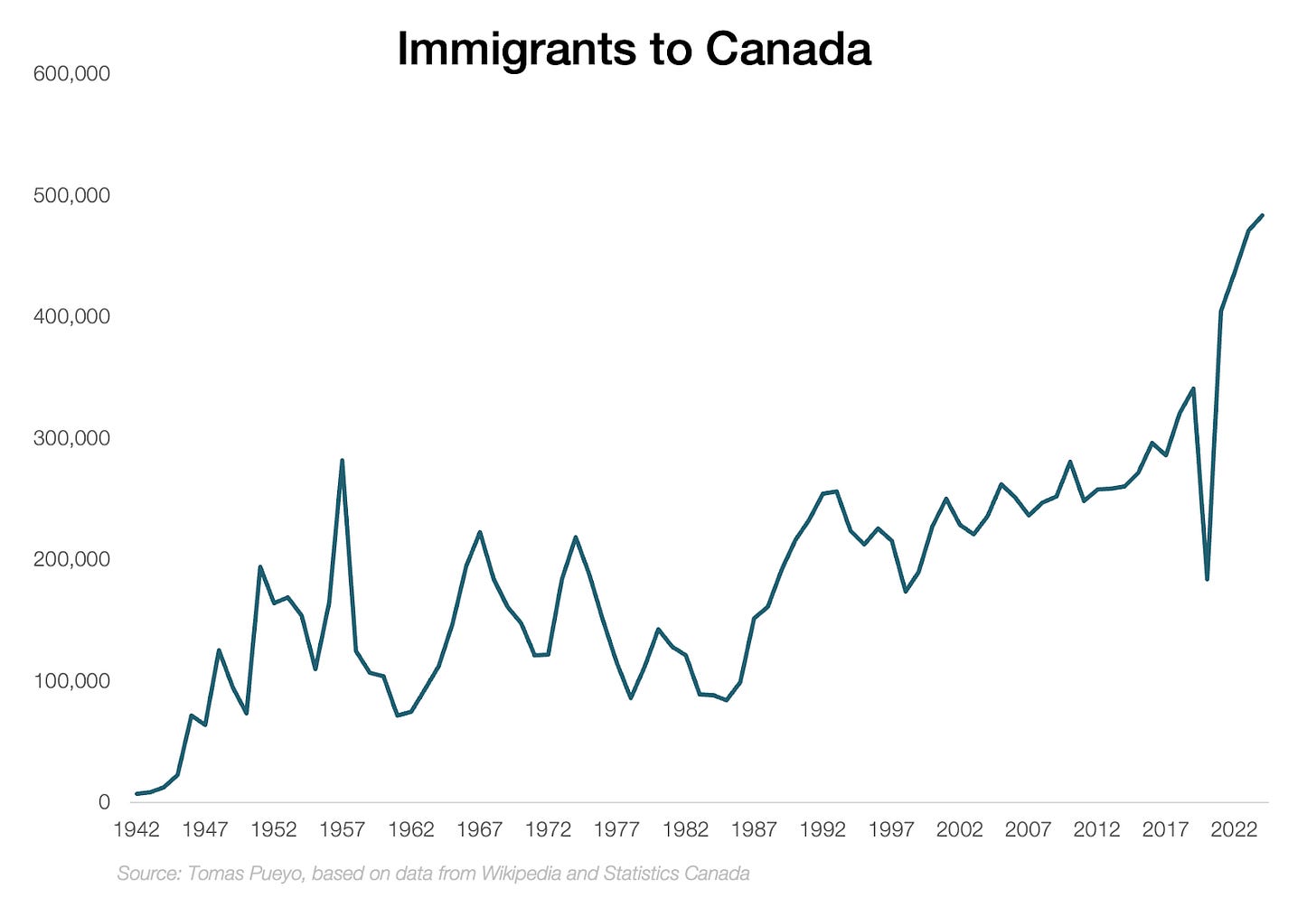

You might have heard about Canada’s recent debate about immigration. In 2024, it received nearly 500k new immigrants—a jump of 70% more annual immigrants vs 2017.

Today, 22% of Canada’s population is immigrant, which puts it up there with other high immigration countries like Switzerland (32%), Australia (30%) and Austria (25%). The US is 15%.

But although this is a lot, it’s less impressive when you take a broader perspective:

Until recently, Canada had not even beaten its historic peak immigration, which was in 1913 with over 400k immigrants. And if you look at annual rates of immigration compared to population size, the recent numbers don’t stand out at all:

Why was there so much more immigration in the past? Because in the 19th century, every country knew that power came from money and population:

The US was extremely successful at attracting immigrants (especially Europeans back then), which made it powerful. Canada had the same ambition. For the same reasons as today.

Canada became a dominion in 1867 and just after that, in 1869, it passed its Immigration Act. From Wikipedia:

At the time, the Canadian government was concerned about expansionist impulses of Canada's southern neighbor, the United States, and sought to increase the population and economic prosperity of Canada to be able to reduce the associated risks. Increasing the population density and development of the Canadian West was considered a strategy for doing so, as the West was seen as a rich source of natural resources and fertile lands. Settling the West would provide new markets for the output of industrial manufacturing in the East.

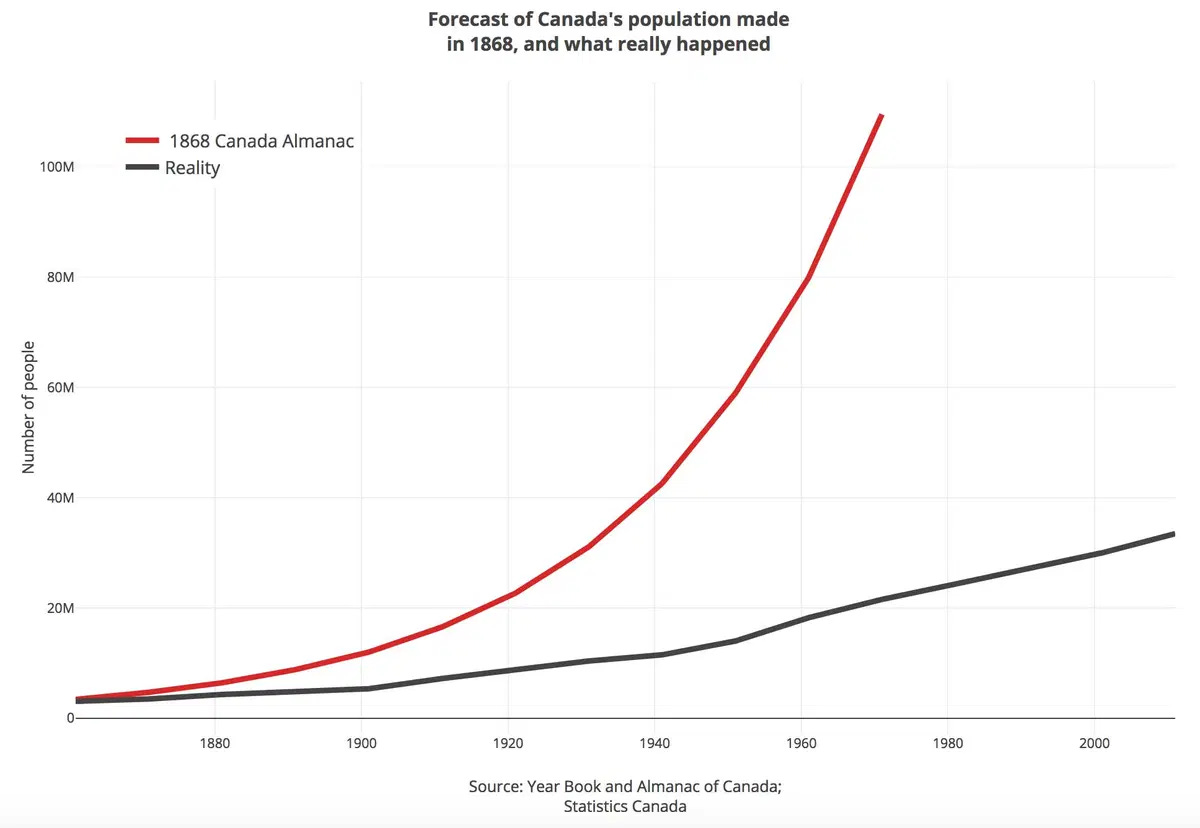

This was followed in 1872 with the Dominion Lands Act: Like the US Homestead Act, it offered 160 acres of land for free if you could farm it. Then followed the National Policy of 1873, Immigration Minister Clifford Sifton's Immigration Campaign of 1896–1905, the British Empire Settlement Act of 1922… Canada purposefully increased its population, and in 1868 it hoped to reach 100M Canadians by the 1970s.

Reality has been different. Indeed, despite all of Canada’s efforts, the immigration data that I quoted is misleading: A lot of people came to Canada on their way to the US. If you look at net migration, the picture changes:

So Canada is used to welcoming a decent number of immigrants, but historically, it grew naturally through births much faster than through immigration. Now, it’s welcoming even more net immigrants as a share of total growth, all while births have decreased: Canada will reach 500k new permanent immigrants in 2025 because that was the plan, which meant an annual growth of the population through immigration of 1.2%. Last year, Canada’s population growth rate was 3%. If it grew at that pace today, it would cross 100M people in 30 years, by 2055.

Alas, this causes problems.

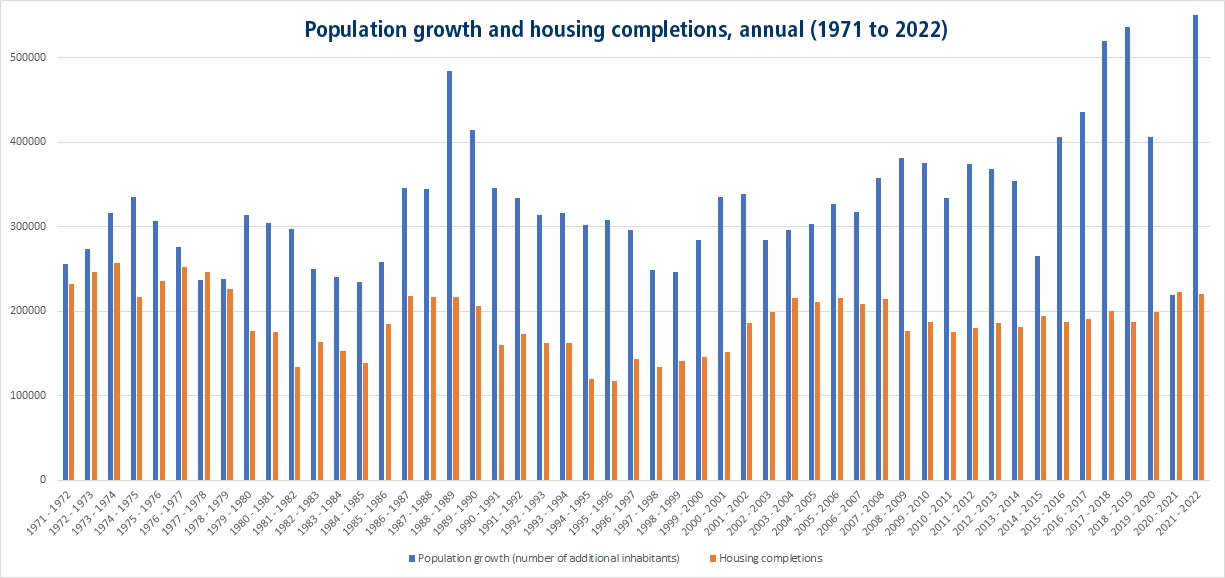

Because the population has grown faster than housing construction:

High housing costs, concerns about long-term productivity, and cultural clashes have decreased Canadians’ excitement about immigration. Canada will have to overcome these issues if it wants to ever be able to face the US. We’ll talk about some of these in another article, but building more housing is a no brainer. If you want tens of millions of immigrants, you must house them! So Canadians regions1—especially in the Great Lakes & St Lawrence Valley—must fight their NIMBYism2 and change laws to make it easier to build. Mind you, this is an Anglosphere issue:

So if Canada wants to become a superpower, it will have to shed its NIMBY culture and mentality. That is unlikely to come from municipal changes, so new real estate development laws will have to be enacted at the federal or regional level.

Once Canada accepts more immigrants, where should they go for the country to be safer against its southern neighbor? Adding more population to its current heartland is good, but there are better places for people to go.

3. Connecting

We saw how disconnected the different population centers are in Canada:

This suggests a few areas in which Canada could increase its population:

a. The Interior Plateau

It might be hard to settle the coast more than it is today because of the mountains, but it should be easy enough to settle the region between Vancouver and the Prairie: Between the two mountain ranges is the Interior Plateau, which already has some population:

The biggest concentration is along the Okanagan River—the meandering line of population in the southern part of the plateau— but the north is not very populated, despite being quite flat:

Temperatures seem acceptable:

And although it doesn’t rain too much—which might be good here—there’s plenty of water from the mountain ranges on each side:

So this seems like a reasonable region for settlement. This is what it looks like:

But who could finance this? The US:

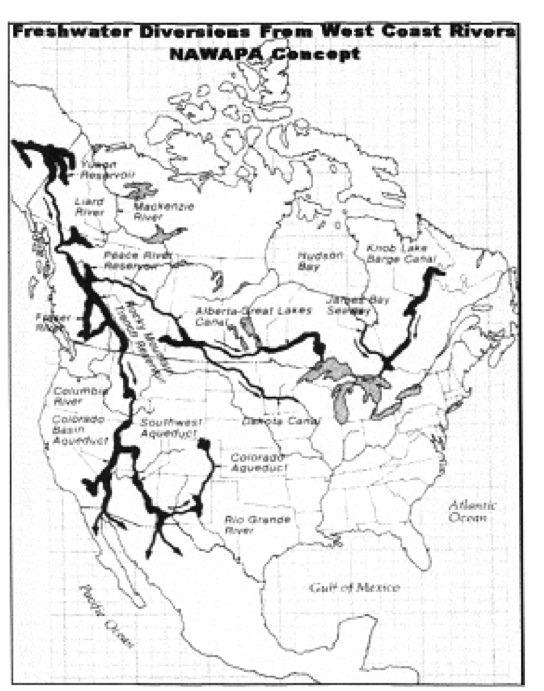

In the 1950s, the US conceived the North American Water and Power Alliance:

Planners envisioned diverting water from some rivers in Alaska south through Canada via the Rocky Mountain Trench and other routes to the US and would involve 369 separate construction projects. The water would enter the US in northern Montana. There it would be diverted to the headwaters of rivers such as the Colorado River and the Yellowstone River.

The US west and south need more water. That country could pay for this, which would see a massive flux of investment in this area of Canada. The water flowing into the US could pay a steady income stream to Canada. And the US’s dependence on Canada would increase—exactly what Canada should be trying to achieve for its self-preservation.

And water would resolve the one reason why the center of the Palliser Triangle is not populated enough.

b. The Center of the Palliser Triangle

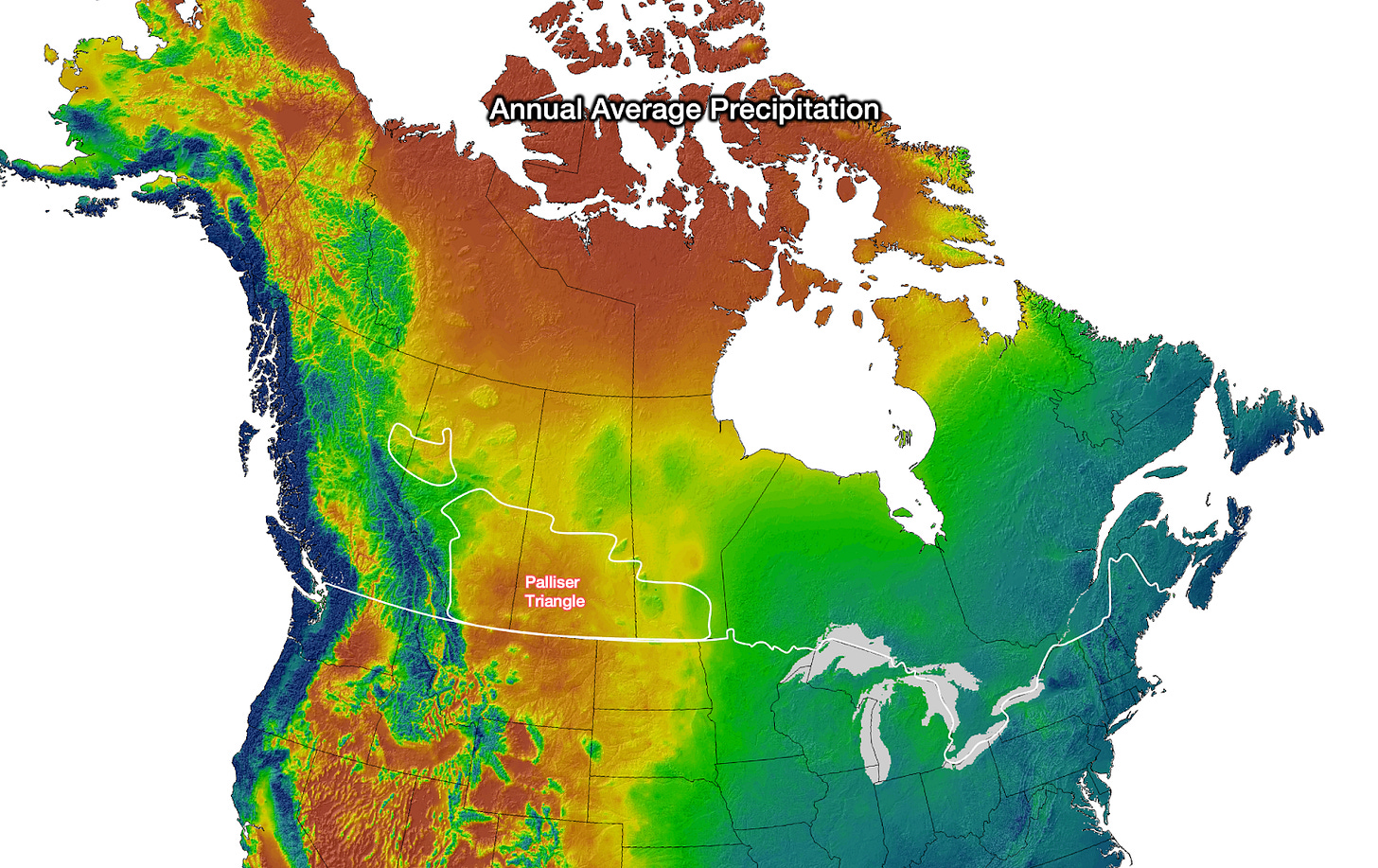

We saw in the previous article that all the Palliser Triangle is very fertile and acceptably warm, but only the north has enough rain.

The Rockies get a ton of rain, but most of it flows north:

Canada has many irrigation waterworks, but none that divert water flowing north towards the south.

It would be expensive to build all the infrastructure needed for Canada to fully irrigate the Palliser Triangle—and potentially send some water to the US—but the country should see it not only as an economic investment, but as a geostrategic one. The more food it produces, the greater its population, and the more the US depends on Canada for its water, the stronger Canada will be.

But agriculture wouldn’t be the only way to develop this area. It should not even be the main one. That honor should go to Oil & Gas.

The same inland sea that made this area fertile also blessed it with some of the biggest reserves of oil and gas in the world. Canada is already the 4th biggest producer of natural gas in the world. Its estimated oil reserves could cover 30 years of world consumption, and its trillions of cubic meters of gas are a virtually limitless source. Canada could become the world’s biggest oil and gas superpower, with its resulting income. But these endowments are not exploited how they could be because of politics:

There aren’t enough pipelines and liquid natural gas (LNG) terminals, because of the years of permit reviews, lawsuits, and community consultations. The result is that production must be sold at steep discounts or even stopped.

Federal caps on emissions will require production limits in the future.

Big pension funds, insurers and green mutual funds now blacklist oil‑sands projects. Companies can still raise money, but it costs more, so only the quickest‑payback wells get drilled.

Nearly every new pipeline, road, or gas plant crosses First Nations land, which requires individual consultations and compensations rather than more centralized politics that could solve the problems more efficiently

These are things Canada could streamline if it took its geostrategic goals seriously.

If it did, it should also diversify where it sends its oil and gas. Right now, it nearly all goes to the US.

Canada should build LNG terminals and pipelines that go to the coasts and the Arctic rather than only to the US.

As you know, I’m a big proponent of fighting global warming. But I don’t think the way to fight it is by limiting the supply from developed countries. The only thing that does is make countries like Russia, Venezuela, Iran, and Saudi Arabia rich. If we really care about human rights, developed countries should produce fossil fuels as long as there’s demand. The way to fight global warming is by making cheaper alternatives to fossil fuels—like solar, wind, nuclear, or synthetic fuels—and capturing CO2. So Canada should feel free to increase its fossil fuel production.

c. Lake Superior & South Ontario

The biggest weakness in Canada’s geography is this hole in population between the Palliser Triangle and the St Lawrence Corridor, in southern Ontario, on the northern shores of Lake Superior and the eastern shores of Lake Huron:

Although this area is reasonably rainy, it’s very cold:

And it’s on the Canadian Shield:

So few crops can be grown there. But that same Canadian Shield that exposes bedrock means minerals are accessible.

Canada has over 200 mines, including for 31 of 34 critical minerals in US and EU lists. Over 50% of global mining companies are listed in Canada. They account for over 50% of global financing. It’s the #1 miner of potash (for potassium, used in fertilizer), #2 for uranium (23% of global production), #5 in gold, #6 in nickel, #7 in cobalt… And a lot of that is on the Canadian Shield, especially in Southern Ontario.

It’s not just because Canada has some of the best mining reserves in the world. It also has political stability and rule of law, abundant water and energy, and proximity to the US as a stable market.

Further developing this industry would also make the US even more dependent on Canada, as there are many minerals for which the US depends on international markets, including lithium and most rare earths.

But for that, Canada needs to lift some of the obstacles it has on developing mining: build more access to remote areas with major deposits (like the Ring of Fire), streamline permit approvals3, and push more of its immigration towards mining—a win-win for everybody.

Mining is not the only way to develop South Ontario though.

Toronto, Montréal, and Ottawa might be well built out, but there’s plenty of room between them. And we don’t even need to go outside of these big cities. The population density of Toronto is ~4,400/km2, and 940/km2 for Greater Toronto. Compare this with New York City’s 11,300/km2. These cities have plenty of room to grow their density. If they don’t, it’s a choice—usually a governance issue.

d. The East Coast

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia (and Newfoundland, and maybe parts of Labrador) are substantially less developed than New England—just on the other side of the border with the US—and even the St Lawrence Valley, inland.

New England is nearly 6x more densely populated, twice as rich, and its main city is 10x bigger than any in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Why is this the case?

The Canadian side is a bit colder, but not by much. Rain is similar. It’s not that. The difference is the mountains behind.

On the US side, the Appalachians create many rivers. The big ones have an estuary that flows to the Atlantic, and big cities appeared at their head of navigation, the furthest point where ships could travel inland. These cities served the entire region, cheaply trading their products with the world. Notably, as their hinterland was made of mountains, they had mining products to trade with the world—timber and furs early on, coal and steel during the Industrial Revolution.

Boston is New England’s perfect example of all of this, but it’s only one of many such cities on the US Atlantic Seaboard. There are also New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia… Each of them traded with each other through their ports, creating a megaregion. They then built railroads to connect with each other over land. All this made the region the political center of the country.

On the Canadian side, in New Brunswick (NB) and Nova Scotia (NS), there is a good port—Halifax—but only one. Every other factor that made the US side succeed does not apply to the Canadian side:

The St Lawrence is a much bigger river, and its head of navigation—Montréal—is much farther inland. It’s also the gateway to the Great Lakes, so all the trade (and population) went there. But Montréal is far from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, so it absorbed much of the trade that could have gone to these regions, rather than complementing it.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, meanwhile, don’t connect to anything. The US to its south is another country, and everything to the west is better connected via the St Lawrence. These regions are the gateway to nothing.

The political power is in the St Lawrence Valley, farther away from this area.

There are few mountains in these regions’ hinterlands, so no mining products. This was especially problematic during the Industrial Revolution, when much of the timber trade that fueled these regions’ growth was replaced with coal and steel—especially for shipbuilding.

The only big, populated Canadian region that NB and NS could connect to in the vicinity was the St Lawrence Valley, and it was already connected via sea, so there was no point in building a railway.

Although it has a similar amount of rain as New England, it’s a bit colder, so has a lower agricultural productivity.

Instead of creating agglomeration effects in a capital, New Brunswick spread its potential across three cities. St John is the obvious best city given its port. The small towns of Fredericton (the capital) and Moncton are much smaller, yet receive disproportionate funding and attention. The result is that St John is smaller than it could be, which makes it harder to compete with other cities like Halifax or Montréal.

Despite this, this region still has many things going for it:

The climate is mild compared to other Canadian regions, and will only get better with global warming

Natural access to global transportation flows is great. Halifax is the closest major American port to Europe.

The Bay of Fundy, between NB and NS, has the highest tides in the world—up to 16m (52 ft). Good for tourism, great for tidal energy—something the country has not explored enough. It’s also why it has good universities focused on oceanography.

The region has lots of great wind, and could have more offshore plants.

There are fossil fuels offshore.

NB has a long border with the US.

Going beyond this, not everybody needs to be physically tied to the land in an Internet-enabled world. Knowledge workers can work from anywhere, and the people they serve can follow. The average knowledge worker is likely to prefer going to Bali, Thailand, or even Spain—warmer, cheaper countries that are also quite safe—but NB & NS4 have their own appeal.

Yet to compete for this type of crowd, they would need to attract prospects with low taxes and great governance. The region already has a streamlined process to give visas to skilled immigrants, but that’s not enough.

If you take a step back here, the irony is great:

Canada wants lots of immigrants.

Why do they come to Canada? Because it’s a place with rule of law.

There are plenty of opportunities everywhere.

Yet because of agglomeration effects, everybody wants to go to the big population centers.

So you end up with a massive country that’s nearly empty, that needs to populate many regions, but all the immigrants cluster like sardines in a few cities, driving their prices up.

Canada should realize that its big asset is its governance. Seen this way, it should be easy to settle places like NB & NS, which benefit from this governance. Just give a visa for NB&NS to all the qualified immigrants that don’t fit in Toronto or Montréal. That process should be streamlined.5

As for its other assets, there’s much NB & NS could do, like:

More high voltage electric connections to the US, to sell excess energy

Centralize power to create agglomeration effects. Specifically, NB should focus its efforts on St John.

At a federal level, Canada should probably choose between Halifax and St John as the one to develop into a large transportation hub. Right now, both have ports competing for a lot of the same business, and port and train expansions can’t be efficient for both.

4. Economic Development

Canada has been growing faster than the US in terms of immigration over the last few years, but its economy has lagged:

Canada must grow faster than the US to be able to resist it, and the best way to do that is by better connecting the country’s economy. Canada is one of the most decentralized federations in the world. Its constitution does not explicitly guarantee free trade between provinces. It only signed a Free Trade Agreement between regions in 2017!

As the RBC reports via Chartboot, Canada trades more with the US than internally!

Intra-Canadian politics maintains a network of trade barriers and regulations that impede trade within Canada itself: Each region has its own rules, regulations, and standards, and companies from other regions must also abide by these rules if they want to sell in Canada.

Many trade barriers are imposed to protect local industries, uphold regulatory standards, generate revenue, and preserve jurisdictional autonomy. However, prioritizing narrow economic interests over fostering broader standards across the country has hindered achieving economies of scale, reduced competition, and contained productivity growth in Canada.—RBC

Business groups have long complained about trade barriers among regions and drawn-out permitting processes. It can take years to develop and build mines, oil pipelines, and other major resource projects.

How bad is it? Well, Canada’s average international tariffs are 1.4%, but the internal trade barriers are equivalent to tariffs of 9% to 23%! Eliminating them could increase Canadian GDP by USD 145 billion and expand the economy by 4-8%!

What can Canada do about this?

The Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) made some progress in 2017, but more than one-third of the 334-page agreement consists of listed exceptions by provinces to the agreement.

Canada must eliminate these and other internal trade barriers. It can do this by:

Harmonizing regulations across provinces

Provinces' mutual recognition of rules

Creating common national standards

Creating a one-stop shop for approval processes

Capping emissions, but not the production of oil & gas6

Thankfully, the new Prime Minister, Carney, is doing exactly that:

"We are committing to table legislation by the 1st of July for goods to travel across the country... free of federal barriers. We can more than offset the effects of any U.S. tariffs by eliminating internal trade barriers alone."

According to Reuters, Carney also said he agreed with provinces that the federal government would provide funds to build transportation links to resource extraction sites and develop a "national trade and energy corridor strategy."

Takeaways

Canada is exposed to the US: It has a smaller population than the US, and that population is too close to the border. Unfortunately, the border is not even uniformly populated, and there are big gaps in population that could be exploited by an invading force.

Its exposure is also economic, as Canada’s economy is weaker than the US’s, has been growing more slowly, and has a huge dependence on the US, as most trade is to and from the US.

But Canada can fight this dependence:

It already welcomes a lot of immigrants. It should continue this policy, refining its approach rather than stopping immigration.

That means stopping its NIMBY mentality and changing laws at the federal or regional level to allow much more housing to be built.

It should develop all the provinces that are empty or have economic potential:

The Interior Plateau is empty, but doesn’t need to be. There is plenty of quality land there.

The Interior Plateau, Alberta, and Saskatchewan could benefit from big waterworks that improve agriculture while exporting water to the US, therefore adding a source of exports while making the US dependent on Canada.

Alberta (mainly, but not only) can further develop its fossil fuels industry, if politicians support it instead of hindering it. This would mean even more money and more US dependence on Canada.

Ontario could develop its mining industry further, with the same result of more money and US dependence.

New Brunswick, Nova Scotia—and even Newfoundland—could focus their attention on St John and Halifax, and attract all the immigrants that don’t fit in the St Lawrence Valley.

Finally, it should focus on eliminating all barriers to internal trade.

Canada should stop thinking about itself as a loose confederation of territories in the middle of the wilderness, and start thinking of itself as a potential superpower that must be able to withstand its best friend when it becomes a bully.

Next, we’re going to explore a few fascinating facts about Canada, like:

How does global warming open up options for Canada?

Why does Alberta want independence more and more?

Why is there a line of lakes across the country?

What goes on in the far north?

Why does the US own a big chunk of its Pacific Coast south of Alaska?

Why is Winnipeg such a big city in the middle of nowhere?

How did a single company have such a massive influence in the history of Canada?

How to deal with the immigration problem?

And more! Subscribe to receive it:

Canada refers to its official regions as “provinces” like Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia, and “territories”: Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut. I think “provinces and territories” is too long so I just call them “regions”.

Not In My BackYard

Usually these are due to complaints by environmental groups and coordination with indigenous tribes, both of which could be accelerated with the right federal priority.

And, in fact, the island of Newfoundland, which has a very similar climate. I haven’t mentioned it much because it’s not contiguous to NB & NS, so it’s less relevant to connect its population to that of the rest of Canada, but much of what is mentioned in this section also applies there. Labrador is even farther and colder, so it applies even less. But some parts of it could qualify.

According to this report, another problem is that some residents of NB & NS are basically xenophobic. Not a great way to attract immigrants! This falls in the debate about the conflicts emerging from Canadian immigration though, so I’ll leave it for another time.

Capping internal emissions pressures the economy to turn green, but limiting production is stupid: This will reduce exports, but it won’t pressure foreign countries into transitioning to green energy. It will just reduce Canada’s income, while competitors like Iran and Russia fill their pockets.

I would love to see an analysis on the benefits of becomeing a US state.

I know unpopular but perhaps not as daft as it is made out to be.

On the other hand, if Trump continues the threats, California, Oregon, and Washington and some of the Eastern blue states could secede and join with Canada...heh, maybe.