How Transportation Technologies Shape Cities

Part 3 of How to Understand Cities

This is Part 3 of How to Understand Cities.

Read Part 1 here: Why Some Cities Thrive.

Part 2 here: Why Cities Are Fractal.

We don’t realize it, but the shape of our cities—from how big they are to what services they have—is mainly driven by one thing: transport technologies.

1. Marchetti

The size of cities is determined by transportation technologies, whether it’s Ancient Rome, Medieval Paris, Industrial London, turn-of-the-century Chicago, or Highway Atlanta.

People live within 30 min of their work. This is the Marchetti Constant.

For millennia, most cities were limited in size because people moved by foot. Even big cities like Ancient Rome or Medieval Paris didn’t grow beyond 3 km in diameter. Indeed, since people walk at a speed of about 5 km/h, and they are only willing to walk up to 30 min to commute1, they were only willing to walk for ~3 km2.

Then, in the early 1800s, London (orange) built the first urban railway. Suddenly, you could live much farther, close to a station, take the train, and in 30 min reach your work. The city grew accordingly. But not uniformly.

Look at the island at the bottom right, for example. It’s there because of a train station. In the mid-1800s, England built many km of railways, including inside London. But trains were slow to start and stop, so there weren’t many stops. People lived around those stops, as long as their total travel time from the railway station to any point in central London didn't take much more than 30 min.

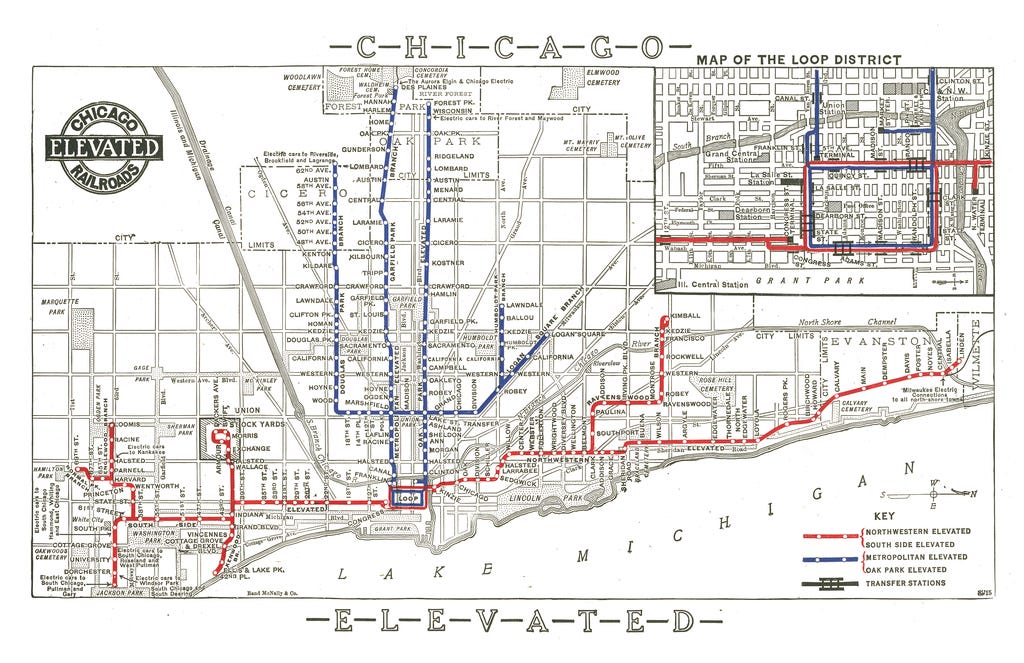

Then, between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, three new transportation technologies appeared: the bicycle, streetcars, and later the subway. Chicago adopted the first two, and grew heavily as a result. This is a map of Chicago’s elevated cars:

And this one shows the streetcars:

This is the city’s resulting size:

Just as the US population was exploding, a new technology flooded the market: Ford’s model T cars.

The result is that many American cities were built around the now ubiquitous car. The urban jungle paved over the plains; highways cemented suburban sprawl. It gave us the footprint of cities like Atlanta.

Cars make all the difference. As they have a speed of 6 to 7 times greater than a pedestrian, they expand daily connected space 6 or 7 times in linear terms, or about 50 times in area.—Marchetti, Anthropological Invariants in Travel Behavior.

This evolution that we have studied across cities can be seen within the city of Berlin, for which the radius grew with the speed of transportation:

This Marchetti constant of commute time can be seen across time and space. Here, rich and poor cities through the 2nd half of the 20th century:

By speeding up commutes, transportation technologies like railways, bicycles, streetcars, subways, cars, and highways grew cities in two dimensions. Then, another technology elevated cities into the third dimension.

2. Roads to the Sky

Before the 1800s, buildings tended3 to have at most six floors.

There were limits due to materials (buildings would crumble under their own weight), water (water pressure couldn’t reach above about six floors), or sanitation (latrines were only at the bottom floor), but the main limit was comfort.

Before the 20th century people prized proximity to the pavement. The first floor, above the hubbub of the street but conveniently accessed by a single flight of stairs, was the floor most sought after. Anything above the second floor was typically reserved for servants. In hotels and tenements, standards and prices fell with altitude. Top floors were considered a public-health risk. The strain of tackling so many stairs, the difficulty of getting outside in the fresh air and the trapped heat of summer played a part in this. It may be no coincidence that the garrett was home to consumptive artists.—New lift technology is reshaping cities.

The elevator changed this. Suddenly, people could move up and down a building quickly.

Coupled with changes in materials (reinforced concrete, steel frame construction) and energy (electricity), skyscrapers started pushing the limits of what was possible. Culture lagged technology, so it still took several decades for people to realize the value of skyscrapers and their upper floors.

The lift not only made much higher floors possible, it gave them a new status and glamour. Rents began to rise, not fall, with height. The penthouse (a word that took its modern meaning in the 1920s) became a status symbol.—New lift technology is reshaping cities.

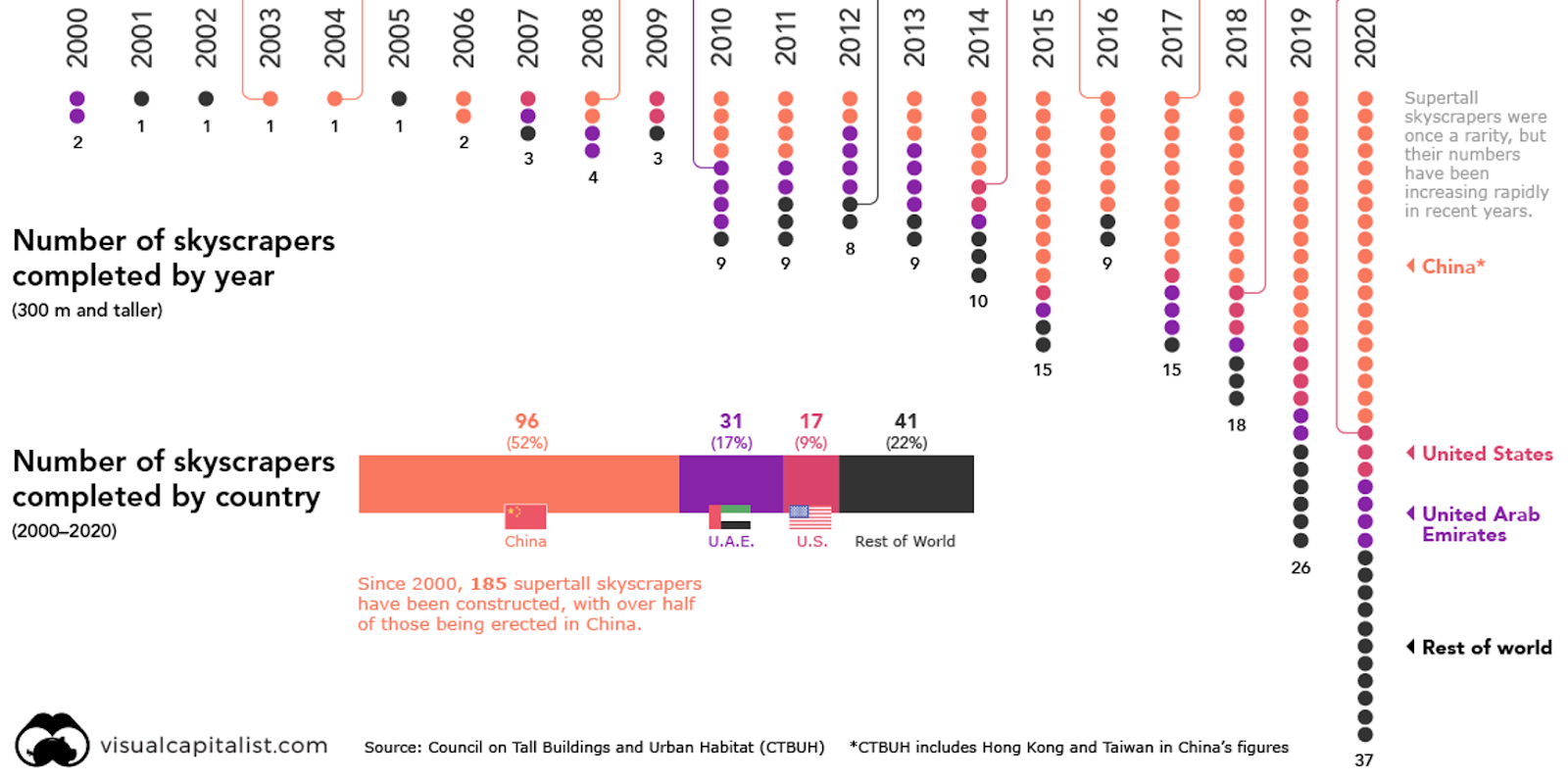

Without skyscrapers, cities like New York, Chicago, Miami, London, Moscow, Istanbul, Shanghai, Tokyo, Singapore, Hong Kong, Seoul, Dubai, Bangkok, Mumbai, Melbourne… are all impossible. Now cities grow horizontally and vertically, and every year they do it faster.

Helped by buildings that are ever taller:

This vertical growth has had a crucial second order effect in cities.

3. Service Density

This is the Interlace in Singapore. It has over 1000 apartments.

If it has an average of three people per apartment, that’s 3,000 people, or an order of magnitude bigger than a standard village. Logically, it can command more of its own services than a normal village can: tennis courts, swimming pools, a putting green, and retail spaces.

Of course, all these amenities make this area very convenient, which means others will want to live either there or nearby. Population begets services, services beget population. Big cities emerge. They get more unique services. They grow even more.

So here’s what transportation does to shape cities:

By allowing people to live farther away, transportation technologies increase the amount of people who can access a city and its services.

By allowing people to live higher up, elevators and skyscrapers allow for greater population density, which means more people can access a city’s services.

Both of these increases, horizontally and vertically, mean more potential customers for services, so more services appear. Because they start to compete with each other for a huge amount of population, they start differentiating. You end up with more types of services.

All these differentiated businesses mean the bigger and denser a city, the more amazing amenities there are: antiques stores, weird indoor sports, niche boutiques…

But this differentiation is not limited to services. More people means more creative and information workers can meet, mingle, and form serendipitous connections across different industries.

This means higher productivity, which means higher wages. People are richer.

Also, corporate margins are higher, so they can invest even more, and be even more productive.

With all these profits, new companies emerge, adding to competition, and thus quality and diversity of services.

All these companies mean more competition for talent, and better conditions for employees.

All these rich employees and companies mean more taxes for municipalities, who can invest in better infrastructure.

In other words, cities build network effects. This is how you get a Manhattan, a Paris, a Tokyo, a Dubai.

Note how Dubai is the extreme example here. It’s in the middle of the desert, and it has no oil, so no natural resources beyond sea, sun, and sand. And yet it has emerged as one of the big metropoles of the 21st century through two quintessential new transportation technologies: a horizontal one (airplanes and airports, transporting people from all over the Middle East and the world4), and a vertical one (huge skyscrapers).

Takeaways

Let’s put together the three articles from the series so far:

In Why Some Cities Thrive, I explained how cities at the crossroads of important lines became hubs and grew more than others. The ones with the best land and the best connections grew the most. Transportation technologies had a role to play here, as connectors.

In Why Cities Are Fractal, I explained the fractal growth of cities. Some will naturally remain small, while others will grow bigger, in a hierarchy of services. The bigger the city, the more services, and the more services, the bigger the city.

In this article, we see how transportation technologies have allowed cities to grow dramatically, both horizontally and vertically, which has allowed the bigger cities to grow even further, and get better across all dimensions, with more and more network effects.

And so it’s no wonder that urbanization only really exploded as transportation technologies flourished. But since then, urbanization has been unstoppable.

This graph underscores the trend, because it treats all cities the same. If all of the above was true, what we should have been seeing over the last few decades is an ever bigger concentration of people in the biggest cities5.

This growth is good for people, since as we’ve discussed, these people have more services. They’re also richer6.

In other words:

Transportation technologies are the primary shaper of cities, and with that, our wealth and health.

If you enjoyed this article, you can read Part 1 here: Why Some Cities Thrive and Part 2 here: Why Cities Are Fractal. Also, feel free to share this article! Next, we’re going to talk about how the cities’ configuration has been shaped by transportation technology. After that, we’ll cover how transportation technologies shaped empires.

Why are we understanding all this stuff about cities and transportation technologies? Because transportation technologies are changing. If we understand how they shaped humanity in the past, we can predict how they will change us in the future.

That’s why Ancient Rome (purple below) was in fact bigger than Medieval Paris (blue).

About half an hour walking at 5km/h.

Normal buildings like residences. I’m excluding specifically grandiose buildings like cathedrals or castles, since their height was core to their goals, and they were not usually inhabited.

The airplanes are not for commuting. As we described in Why Some Cities Thrive, airports are connectors, like lines such as rivers or roads. The emirate invested heavily in its connections to cities around the world, which made it hyperconnected, which then attracted people, who could all be accommodated in high-density skyscrapers, allowing lots of amenities to be created for them, further increasing Dubai’s fame and attractiveness.

My guess is that most cities have been pushing back against more growth. Manhattan, for example, has a smaller population today than it had in the early 1900s. Many capitals like Paris, London, or San Francisco have decided they don’t want to grow their population any further. All the NIMBY movement against density has halted this huge natural trend towards bigger cities. But where NIMBYism is not prevalent and cities are left to grow to their natural potential, the biggest ones keep growing and growing. Source.

It costs more to live in a city, but the higher income usually makes up for it.

Nice article. In the wired suburbs we now see dead malls returning to become villages for the over 50 crowd and the home IT worker

Will empty city high rises revert to vertical villages for millennials ? Have to wait for your next installment.

Hi Tomas. What a fascinating read. Thank you! you may find this story interesting that I wrote on e-mobility: https://chriskrafft.substack.com/p/how-e-bikes-make-life-better