Why Doesn't North America Speak French?

Why is French only spoken in Québec, and not all of Canada? Why not in all of North America?

You might think you know the answer, but do you know the root cause? Yes, France owned what’s now Québec, but why did it go to war with Britain? And why did the British prevail? Why didn’t the British eradicate the French after winning? Why did the French language survive over 250 years of British hegemony? If you asked somebody in 1700 what languages would be spoken in the future in North America, would he have known that English would prevail?

These are the territories that France claimed by 1750:

This is a map of how things had changed by 1763:

How do we go from a massive French presence in North America in 1750 to its disappearance 12 years later? How did the British take control of nearly the whole continent so fast? Why does most of North America speak English and not French?

What you might not know is that, by 1750, the region was already de facto British: In the middle of the 18th century, New France had 60k people while the British colonies had about 1.2M—20x more! Why?

The main reason for this was immigration: While France had sent 16k settlers to the St Lawrence Valley by the early 1700s, and a total of 30k by 1760, British colonies had received 10x that, including ~125k Brits and 100k Germans!1 Why?

This is even weirder if we consider that, around that time, France was by far the most populous country in Europe:

So why didn’t France send more settlers to Canada, while England kept sending settlers?

1. Population Density in the Motherland

One of the reasons is this:

In most European countries, the population was growing slowly at the time. And rulers knew power came from people: They could farm more food and fight more wars. So they were cautious about sending their subjects elsewhere. For example, Spain sent ~200k people to America from 1492 to the 1650s, and only about 400k by the 1800s. Portugal had sent ~400k. France, about 90k by 1775. These countries actively preempted emigration: Only Catholics could go, for example. Also, the goal was to extract as much value as possible from their colonies, not to settle them. In Latin America, that meant controlling local populations to extract silver and take care of plantations. In Canada, that meant controlling the fur trade, a lot of which could be done by trading with Native Americans.

This was not the case in England. It already had a higher population density than many other European countries before the Black Death of the 1300s. Its population grew faster afterwards. By the early 1700s, England’s population density was among the highest in Europe, and it was causing pressure in farmlands.

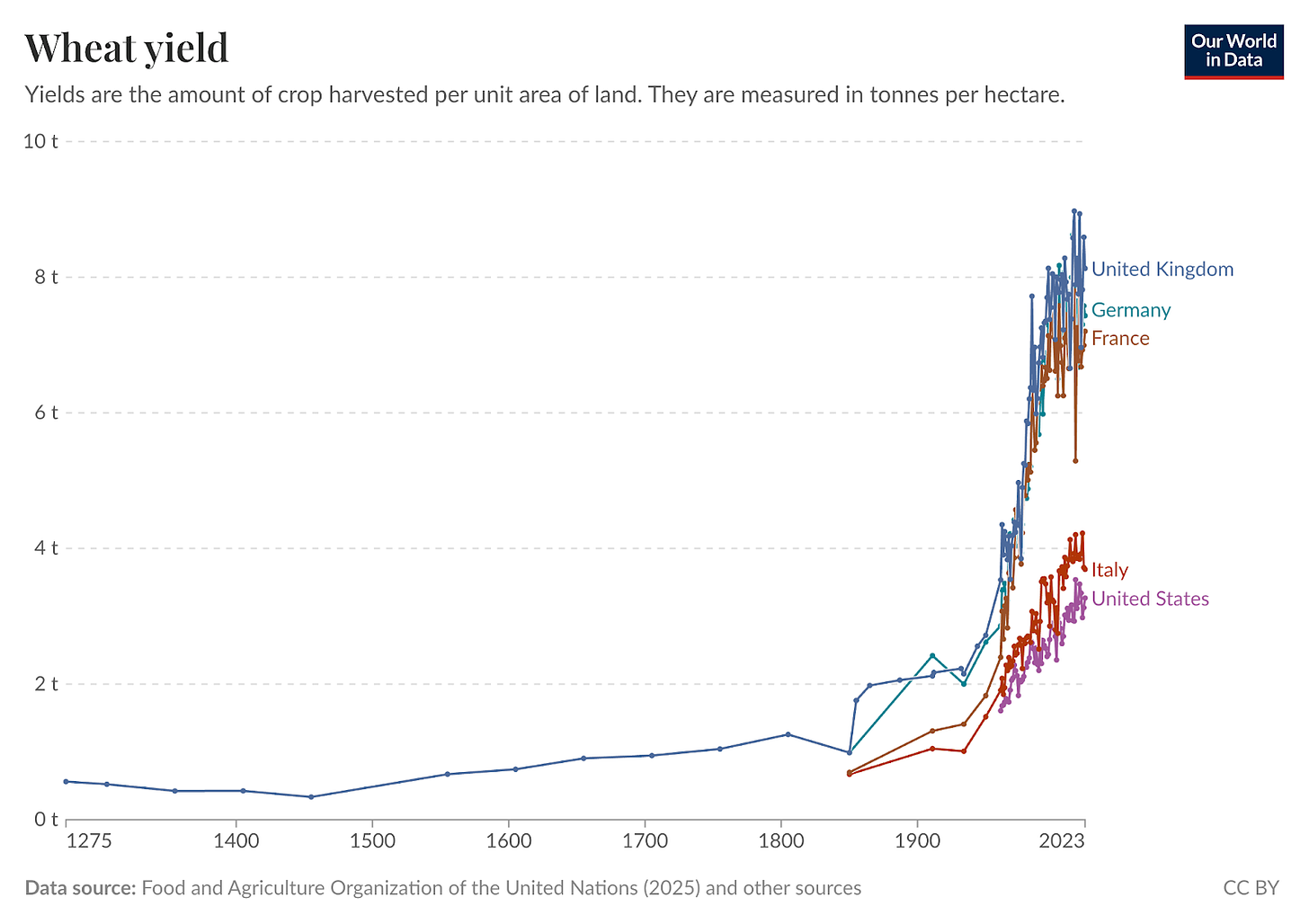

But why did it grow so fast? Grain yields seem to have been higher there (and in Germany) than elsewhere in Europe:

It was hard to find information about comparative agricultural productivity across Europe in the 1500-1800 period, but I did find this:

So what happened is that farm productivity was much higher in England2 than in the other imperial powers.3 In a Malthusian world, that translated into a higher population density and a surplus of population, which brought population pressure to farmlands and a push for emigration. By the 1600s, emigration to America was an escape valve for England.4 That wasn’t the case elsewhere in Europe.

2. Timing

You might have noticed that I said France sent ~15k immigrants to Canada by 1700 and ~30k by 1750, but by then, the French population was only 60k. Meanwhile, the British colonies received ~300k immigrants, but by 1750 their population was 1.2M.

Why did the immigrants to the British Colonies multiply by 4 but the ones to French Colonies only multiplied by 2?

One big reason is the timing: British immigrants started arriving much earlier. Remember this graph and look at the left:

Many more people had moved to the British Colonies, much faster. They had more time to reproduce.

3. Fertility

It’s also true that the French took a very long time to kick-start their fertility in Canada. In the 1600s:

Approximately two-thirds of the French immigrants returned to the Old World or died unmarried in Canada. Only 3,400 French settled along the St. Lawrence River and laid the foundation for the new colony.—Les Filles du Roi

Why?

The vast majority of migrants were men: soldiers, fur traders, and missionary priests.

Soldiers and missionary priests were men for obvious reasons.

France sent missionaries and priests to expand Catholicism in the Americas, and they took spots that could have gone to women, increasing the sex imbalance. Many of them later returned to France.

Trappers had a very itinerant lifestyle, always moving around to hunt and trade furs. Not a lifestyle conducive to attracting women or forming families at that time.

Without French women, trappers and soldiers tended to pair up with indigenous women, but these pairs didn’t increase the population of the colony. Why?

Intermarriage was encouraged early on because it created ties with locals. But this actually hindered colony growth: Apparently, indigenous women didn’t follow European-style marriages where the nuclear family remained united. They preferred staying with their own tribes, and raised their children as natives, not as French. So much so that, to this day, there’s a recognized Canadian indigenous tribe of Métis, who are mainly descendants from these unions. Many times, the men would follow the women, actually draining the colonies of their population rather than contributing to it. Finally, intermarriages frequently led to disease, since many natives were not immune to infections brought by Europeans.

It was only in 1669 that France sent women—about 800—to reproduce with Canadians. That effort was successful, since most got married and started having babies immediately. At that point, their fertility was as high as the British, but it was too little too late.

The picture in the British colonies was the opposite. British immigrants included more women for a couple of reasons:

Many settlers escaped England because of their religious beliefs: They were Puritans and disagreed with the Church of England. They tended to emigrate in whole families, and continue reproducing once they arrived in the US.

Families also moved together because of headright: The head of household was granted land based on the number of people he brought with him.

The majority of economic activity in the British Colonies was farming, very conducive to settled families, so it attracted many.

The results of all these differences was that in New France before 1670, for every woman, there were 2 to 10 men. In New England, that ratio was 1.5. Virtually all women married in both, but a much higher share of women in the British Colonies meant more children overall.

4. Healthier New England

Couples had a similar fertility rate in New France (around 6 to 9) and New England (around 7 to 10). However, around 40% of children5 died in New France but only 10% to 30% in New England. This meant that two parents would have 5 surviving children in New France, but ~7 in New England. In two generations, that would mean multiplying by 6 in New France but 12 in New England!6

From what I can gather, the main reason was the cold: It could kill children, either by increasing their vulnerability to respiratory infections, or through famine caused by later and scarcer harvests in New France. With a better climate, New England had less of these issues, and fewer of its children died.

5. Ideas: Governance, Incentives, Religion, and Marketing

Prospective settlers to British Colonies had a very strong incentive to move, and very few barriers to do it.

The British government incentivized emigration. One way was through the headrights I mentioned before. Another was through very liberal concessions of colony rights to private investors.

It also didn’t stop people who wanted to leave England. For example, there was conflict between the Church of England and Puritans in England in the early 1600s, so tens of thousands of Puritans left.

All this gave wings to private initiative looking for returns in America, which could come from many sources:

Trade, mainly timber, furs, fish, and tobacco

Real estate, as land became more valuable with more settlers

Headrights

As a result, investors had an incentive to market to their compatriots the amazing opportunities that could be found in America, and they did. They recruited aggressively in England.

Once settlers landed, the conditions were truly better in New England than England, as it was less crowded, there was much more timber7 for construction, the strong economy and increased scarcity of people meant salaries were higher…8 Through word-of-mouth, they let their friends and family know about the amazing American opportunities, and many more came, and most stayed.

All these conditions were the opposite in New France:

Being a much more centralized country, the French King heavily controlled the settlement of New France. For example, Protestants (Huguenots) were not allowed to emigrate! You had to be a Catholic, upstanding citizen to go.

Once they were there, the opportunities were much more narrow: Either become a trapper or a farmer. This was not very compelling to other Frenchmen, and word-of-mouth did not encourage further settlement.

The government didn’t create a strong incentive structure to emigrate. There was no equivalent to headrights.

Everybody knew that New France was quite cold. Voltaire famously called Canada “a few acres of snow”.

New France was especially not compelling for women, as the lifestyle was less suitable for them.

All these things also meant no private initiative to settle New France. And the French Crown was not especially good at marketing. It was very hard to even gather 800 women to send as Filles du Roi.

This had another consequence. Whereas New France settlers didn’t push aggressively westward, the British ones did: More and more immigrants were coming, and all the best lands were already taken, so the British wanted to push west, to the other side of the Appalachians, to the Ohio River—an area that France claimed as theirs.

France saw the writing on the wall and started building forts along the Great Lakes, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers. Settlers pushing westward started clashing with the French, and that’s what sparked the war.

6. Individual Productivity of American Fields

I’ve touched on this, but it’s worth explaining further: The nature of the economics of New England specifically was very conducive to European immigration in a way that was not true for either New France or even the southern British Colonies like the Carolinas.

Production in New England didn’t require a lot of people, but it did require entrepreneurship. In that area, what grows is crops like wheat and barley, which don’t require lots of labor, just land. So you wanted as much land cultivated as quickly as possible, which required individual initiative, and hence free emigration with land grants (like the headright) was optimal. Since there was an inordinate amount of land to be cultivated, hundreds of thousands of immigrants arrived to claim that land.

This was not the case elsewhere. In New France, trapping required very few people, especially since a lot of the hunting was carried out by natives. And the outcome could be controlled, as the sale of these furs was carried out in Europe, so it required shipping.

In Spanish colonies, the first goal was mining. This required lots of workers, who could be easily controlled by owners. This incentivized slavery or indentured servitude—of either natives or African slaves.

Plantations are similar: Plants like cotton and tobacco require a lot of work to cultivate and treat. This fostered big plantations and the slavery trade, both of which were less compelling for poor immigrants who couldn’t afford either the land or the slaves. This is why, within the British Colonies, New England grew much faster than the southern colonies.

7. British Power

So far, I’ve only given you reasons why the local British population in American colonies was much bigger than in New France. But these settlers were not the only ones to fight in the conflicts that emerged between them. Britain and France also sent troops.

Most able-bodied Canadian men fought—about 15,000. That was half the British contingent of about 30,000 locals—of which 20,000 came from Connecticut alone. We already saw why the British colonies could muster stronger forces: a much bigger population.

But on top of this, Britain sent over twice as many troops (20k) as France (~7k regulars plus ~2k marines). Why?

France knew that the British American population was 20x bigger than the Canadian one. It did not hope to win that war. But war bled into Europe, so France actually hoped to win the continental war, in order to demand the restitution of Canada from Britain. Therefore, the force sent to Canada was just a means to strengthen its negotiation power and weaken the British, not to guarantee victory.

On top of that, Britain had emerged earlier in the century as the decisive maritime superpower. It blockaded the American coast, making reinforcements and supplies really hard.

France didn’t have a massive interest in Canada anyways: The colony lost money, whereas its Caribbean colonies made a lot of money through sugar and tobacco.

The weaker French forces, combined with the fact that the British colonies could supply their forces indefinitely, while the Canadians had a much more limited harvest in the north, meant that they were virtually guaranteed to lose.

Takeaways

So if you boil it all down, there were four root causes for why Britain won against France in America, and today most Americans and Canadians speak English and not French:

The agricultural revolution reached England before France

British colonies were farther south than French ones, making them much more productive and compelling

Governance difference: the British had more freedom, so there were more religious emigrants and more private initiative. The incentive of free farmland also drew people. France was too restrictive.

British hegemony in the sea

The Aftermath

After conquering Canada, the British did kick a few French-speaking people out of Acadia, but they didn’t do the same in Québec: There was no risk of rebellion because the war had definitively settled the issue of ownership, and removing the French would have utterly destroyed the local economy. Since New Englanders now had plenty of space to expand in the Ohio River Valley, kicking the French out would have just destroyed their production—and taxes.

In fact, the Seven Years War emptied the British coffers, so they raised taxes on the colonies to counterbalance. This was not popular.

Add to that the fact that the British had just trained a new army of settlers and had mixed them across all 13 colonies, making connections between them, and the seed of the American Revolution was planted. It wouldn’t take long: It would start just two years after the end of the Seven Years War. France saw this as an opportunity to get back at Britain; this time it supported the revolutionaries, and within a decade, Britain had lost one of its most profitable colonies.

Canada remained in the hands of Britain and only fully left in 1982. During all this time, it contained the growth of French and English settlers pushed farther west. And this is why North America speaks English and not French.

Next, we will dive into why some people from Alberta (and Saskatchewan) want independence from the rest of Canada, and why Winnipeg is where it is. This will end the Canada series for now.

According to Altman, Ida and Horn, James (eds) (1991), 'To Make America': European Emigration in the Early Modern Period, University of California Press (Berkeley).

Why? This is something I’m going to spend much more time on in the future. For now, you can just read the Wikipedia article on this.

Save for the Netherlands. In fact, from everything I’m reading, I’m reaching the conclusion that the true innovator in everything preceding the Industrial Revolution was the Netherlands.

This was a key trigger of the Industrial Revolution, too.

Defined as either those who died before 15 years of age or before having children.

I’m talking mostly about New England here because the colonies farther south were more problematic. Chesapeake Bay had malaria, for example. There, child mortality rates were higher, and population growth slower.

Most English forests had been either cut or were in the process of being cut by that time.

Wages in England were low because of the overpopulation there. As they arrived, most workers were actually indentured servants, so they had virtually no income. But after that, they could either make more money by working their own fields, or command high wages through the nascent industries in America: cod, timber, wheat, tobacco, indigo, cotton…

Great article! I do want to clear a common misconception that folks outside of Canada often have: French is spoken in far more than just Quebec. There are many Francophone communities in Ontario, and scattered across the Prairies and the Maritimes/Atlantic Canada. New Brunswick has both English and French as its official languages---the only province in Canada where this is the case! I live in Ottawa, and being right on Ontario's border with Quebec (as well as the nation's capital), it's a super bilingual city. The French culture and accents vary quite a bit across these areas as well. It's much more diverse than many folks beyond Canada realize. (Maybe those variations are worth a future post?)

Very interesting article Tomas, as usual, but it doesn’t answer two questions:

1. The French territory you show in the first map isn’t entirely cold. Louisiana, for example, clearly has a warm climate, so cold weather doesn’t explain why so few French settlers were sent there.

2. Why did the French focus on Quebec, a region so cold and inhospitable, compared to southern territories? Why didn’t France prioritize Louisiana, for instance, which had far greater potential?