Why Was Jamaica a Pirate Capital?

I’ve been publishing fewer free articles lately as I’m busy with many things, but premium readers receive one article religiously every week. Most notably, all my series on the Game Theory of Sex are under paywall. Here are some of the latest premium articles:

Family Wars, one of the most popular of the last few months, explores why family members enter in conflict: parents vs their children, siblings, grandparents…

In YKINMKBYKIOK, I explore why we have the kinks we have.

The quarterly update looked into the reproductive function of long hair, crop tops, low raises, glances, kissing, or how cultural phenomena like feminism can emerge from simple sexual ratios.

In There Are 2 Types of Environmentalist, we made a difference between those who want to push the world forward and those thinking backward.

In Cities Are Blurring, we realized how the network effects of cities weaken, and how some cities will specialize as a result, while in The Fight for the Remote Worker, we analyzed what cities can do to thrive in the 21st century.

In Stories vs Systems, I explained how humans consistently misunderstand why things happen the way they do.

In What Future Problems Matter?, we broke down why problems like fertility, overpopulation, or crime matter much less than AGI or retirement funding.

Today’s free article is a continuation of the series on the history of the Caribbean, with parts 1 and 2 here.

Why do Jamaicans speak English, when most of the neighboring countries don’t?

Why are most Jamaicans black?

Why was it a pirate capital?

Why did these pirates drink rum?

All of this can be understood from this map of shipping today:

Notice how Jamaica is in the middle of all these shipping routes—yet few actually stop there. Compare this with other ports in the area:

It’s not the first time Jamaica has been in the middle of the action without getting much of it. These are Spain’s trade routes 500 years ago:

Spanish ships would sail from Europe to gather silver from its mines in Zacatecas (Mexico) and Potosí (Peru), as well as luxury goods from China, via Mexico.

The ships arrived mainly via San Juan de Puerto Rico and returned to Europe from Havana, in Cuba.

Why did they follow this path? In A Brief History of the Caribbean, we saw how Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Hispaniola (the big island in between; today’s Haiti and the Dominican Republic) were big enough islands to produce resources to staff and restock ships, and they had good ports to protect and repair them.

Also, Puerto Rico was the closest to the ideal path of ships coming in, while Cuba was in the path of ships leaving the region for Spain. Why?

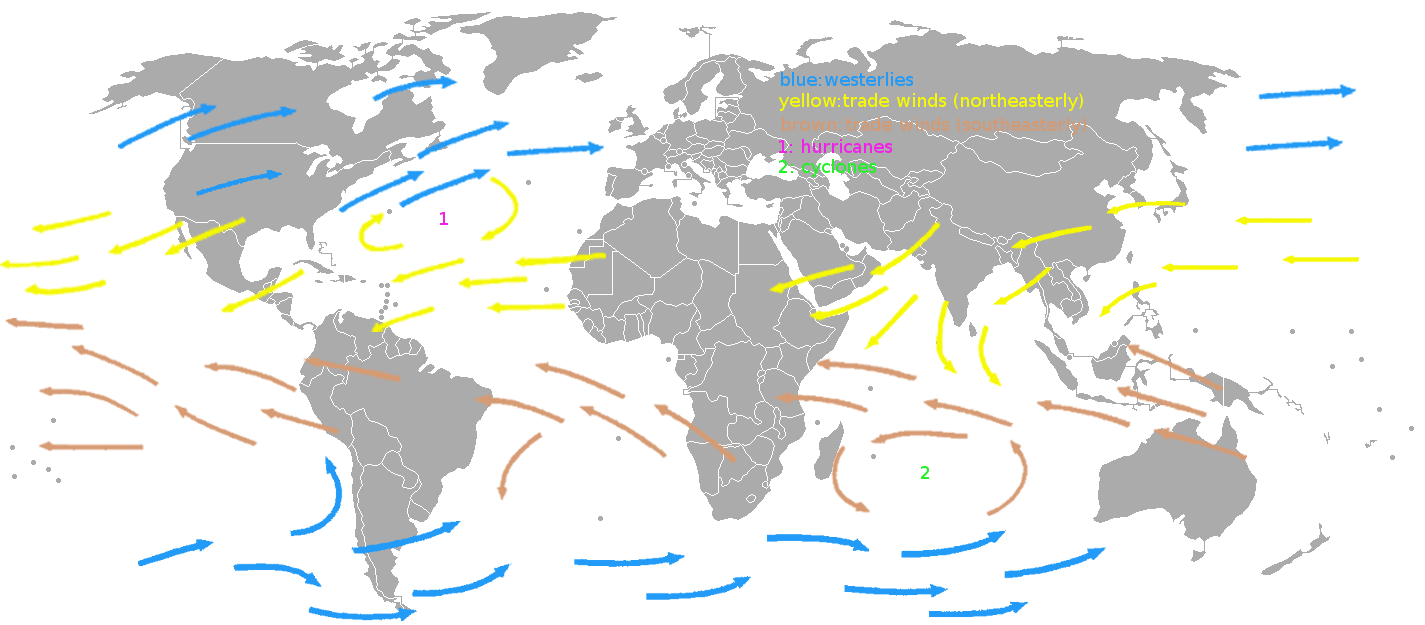

Winds blow westward in Puerto Rico, and eastward farther north.

These winds cause a gyre in the sea currents of the Atlantic, which further accelerated ships’ movement:

In the Caribbean, that translates into this:

You can see, for example, these currents in action in a satellite picture of Martinique, Dominica, and Guadeloupe, small islands in the southeastern Lesser Antilles:

So ships were just following physics to optimize their route in the Caribbean: Go south to travel westward to America faster, and sail north to travel more quickly back to Europe. This made some regions much more useful than others:

Mexico, Panama, and Colombia were useful as producers and intermediary entrepôts, and San Juan de Puerto Rico, Havana, and to a lesser extent, Santo Domingo, were important as the first and last stops for Spanish ships.

In the beginning, the fact that these different places had different value didn’t matter: The Spaniards were the only power in town, and they controlled everything. This is the Caribbean in 1600:

But when news ran around that Spain was unearthing from the region ungodly amounts of silver to finance its European projects, others wanted in. Of course, the first ones to innovate are usually entrepreneurs—ideally sanctioned by their governments. So French corsairs and English privateers emerged to challenge Spain and attack its settlements and ships in the Caribbean.1

Now put yourself in the position of an “entrepreneurial individual” who sees poorly-defended money moving around in consistent patterns. What port will you use as a base?

These islands in the middle are perfect:

They don’t belong to the bigger islands that Spain really cares about: Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola

There are a lot of islands in the area, so it’s hard to defend them all

They’re in the middle of all the shipping lanes, so it’s easy to use them as a base to intercept convoys

But they don’t participate in these shipping routes—which would have given their populations a reason to keep peace for trade to continue flowing

Pirates can easily use them to hide and escape, since they’re in the middle of many island hideouts in all directions

That’s why the hotspots of piracy in the Caribbean emerged here: Jamaica and Isla Tortuga.

Now, Tortuga is a small island, farther away from the action, without great natural ports.

That meant it was completely useless to Spaniards, but quite useful for pirates, who had many escape routes to dozens of islands around it.

So pirates used Tortuga as a base.

Spaniards didn’t want to give a base to pirates, so pirates took over the island several times—not in their own name, but in the name of Spain’s enemies: England, France, and even the Dutch Countries, who were all pretty happy to see Spain undermined. Each time, the pirates would escape and return later, since Spaniards had to leave because they were overstretched across all the Caribbean islands. So their hiding and partying continued.

If Tortuga had been the only island conquered by foreigners, Spain could have taken it back. But foreign powers were weakening Spain everywhere. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, they started attacking Spanish convoys, which forced Spain to focus its investments on defense rather than attack, and to spread them across the defense of both ships and land.

Their ship defenses included the treasure fleet.

And their land defenses focused on key cities such as Havana, San Juan, Panama, Cartagena de Indias, Veracruz, and Santo Domingo.

In the 1600s, the French, English, and Dutch were gaining power and started coveting Spain’s riches. Where should they start attacking to establish beachheads? In places Spain didn’t care much about—the Lesser Antilles.

This presence allowed them to establish sugar plantations and make a lot of money, leaving them eager for more. The more these foreign powers encroached, the harder it was for Spain to keep a stronghold in the area. It was only a matter of time before Spain would lose something even more valuable: Jamaica.

Do you see what looks like a lake in the southeast, surrounded by a big plain and a peninsula reaching into the sea? That is Kingston Harbor, the seventh largest natural harbor in the world. Zooming in:

The northern edge of this natural port became Kingston, the present-day capital of Jamaica. But the tip of the peninsula that creates Kingston Harbor and juts into Port Royal Harbor was more useful early on: closer to the sea, surrounded by protective water, and easier to escape if an invading force arrived.2 So that’s where pirates established themselves to attack the Spaniards.

Since it was such a big island in the middle of the Caribbean, Jamaica mattered a lot more to the Spanish than Tortuga and the Lesser Antilles. But not as much as Cuba, Puerto Rico, or Hispaniola. So when the English attacked it in 1655, they won. Spain attempted to regain it several times, but failed. The English, eager to weaken Spain, used pirates to attack Spanish ships and colonies, putting them on the defensive and preventing them from raising a force that could retake Jamaica. Port Royal became the pirate capital of the Caribbean.

Since Port Royal served as a pirate hideout and a place to spend their money, it was full of taverns and brothels.3 At its peak around 1690, it was the most populated city of Britain’s colonies, with more people than Boston and New York.

Alas, people have to relearn the same lesson over and over again: Don’t build a port too exposed to the sea—especially in earthquake prone areas.

In 1692, an earthquake and consequent tsunami destroyed Port Royal.

Some of the city sank underwater.

Some of the city sank into the ground as it liquefied.

We can see one of these still standing to this day:

Survivors of the disaster and the new people coming to the region gradually left Port Royal for Kingston, situated on the plain on the opposite side of the harbor.

By the late 1600s, the states of Spain, France, England, and the Dutch Countries had become stronger and started signing peace agreements to stop hostilities and focus on making money with trade. Pirates were less useful, so the states started fighting against them. Within decades, most pirates either settled, were arrested, or died.

This is why, at the beginning of the 1700s, Spain still controlled the most valuable parts of the region, but the other powers had established strong bases in all the less valuable spots:

The Lesser Antilles, Lucayan Archipelago, and the center of the Greater Antilles (made of Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico) had all been taken over by other European states. Soon, the money they made from plantations had demonstrated the value of the Caribbean, and they would use these lands as beachheads to take over more parts of the region.

In the 1800s, Europe was ravaged by the Napoleonic wars, during which France stopped focusing on American possessions like Louisiana and Saint Domingue.4

Soon after, the Spanish territories in America, inspired by the nationalist movements of Europe, demanded their independence. Once Spain had lost continental America, the Caribbean was not as useful anymore. It hung onto the islands of the Caribbean that had been the most valuable in the past—Cuba and Puerto Rico—until the emerging power of the US took them over in 1898.

This is why Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico speak Spanish to this day: They were central to Spanish interests in the Caribbean for centuries. And it’s why Jamaica speaks English, though surrounded by Spanish-speaking countries: The island was not as important in facilitating the flow of goods in the Caribbean as it was in disrupting it. So England took it over as early as it could, in opposition to Spain, and it lasted long enough that now Jamaicans speak English and not Spanish.

Jamaica’s central location in the Caribbean without being a shipping lane stop is also why it was a pirate capital. But it doesn’t explain many other things about Jamaica:

Why did pirates drink rum?

Why are most Jamaicans black—more so than, say, Puerto Ricans or Mexicans?

Why did Port Royal suffer an earthquake?

Why Jamaica is such a cultural capital, punching far above its weight with exports like Reggae or Rastafari?

Why does it export some of the best coffee in the world?

What are other sources of income for Jamaica?

Why is Jamaica the way it is today?

We will cover all of that and more in this week’s premium article.

Usually, with a heavy undertone of Protestants vs Catholics. Note that Portugal and Spain, both Catholic, mostly avoided war. But when England became Anglican, wars erupted between them. France was mainly Catholic, but had a strong Protestant minority (Huguenots). These Huguenots were the breeding ground for French privateers, or Corsairs.

It was surely more useful, otherwise pirates wouldn’t have established themselves there. I could not find the reasons though, so I am speculating here.

At least 10% of the buildings were taverns, and I read a claim that 25% of the buildings either served alcohol or prostitutes.

It sold Louisiana to the US. Saint Domingue was its colony on the island of Hispaniola. It couldn’t squash a revolt in the western side—now Haiti—and couldn’t fend off Spain in the eastern part, now the Dominican Republic.

There is a really interesting interaction between geography and the dominant energy source needed for oceanic shipping. During the Era of Sailing ships, the geography of wind patterns played an important role in which geographical regions were important (as you document). When coal displayed sail, the geography of coal fields and coaling stations completely reshaped the regions that were strategically important. Then when marine diesels displaced coal, the oil fields reshaped the regions that were strategically important once again.

Why is Haiti such a basket case compared to the Dominican Republic?

What would it take to bring it up to the same standard? - would it be doable for the international community to build a functioning state?