The $100M Worker

Tech companies are trying to attract workers with over $100M compensation packages. How can this make sense?

It does.

After today’s article, not only will you understand the logic. You’ll wonder why there aren’t more companies doing the same, and spending even more money.

Not only that. You’ll also understand how fast AI will progress in the coming years, what types of improvements we can expect, and by when we’re likely to reach AGI.

Here’s what we’ve said so far in AI:

First: We’re investing a lot in AI, but there’s massive demand for it. This makes sense if you believe we’re approaching AGI.1 So it’s unlikely that there is an AI bubble.

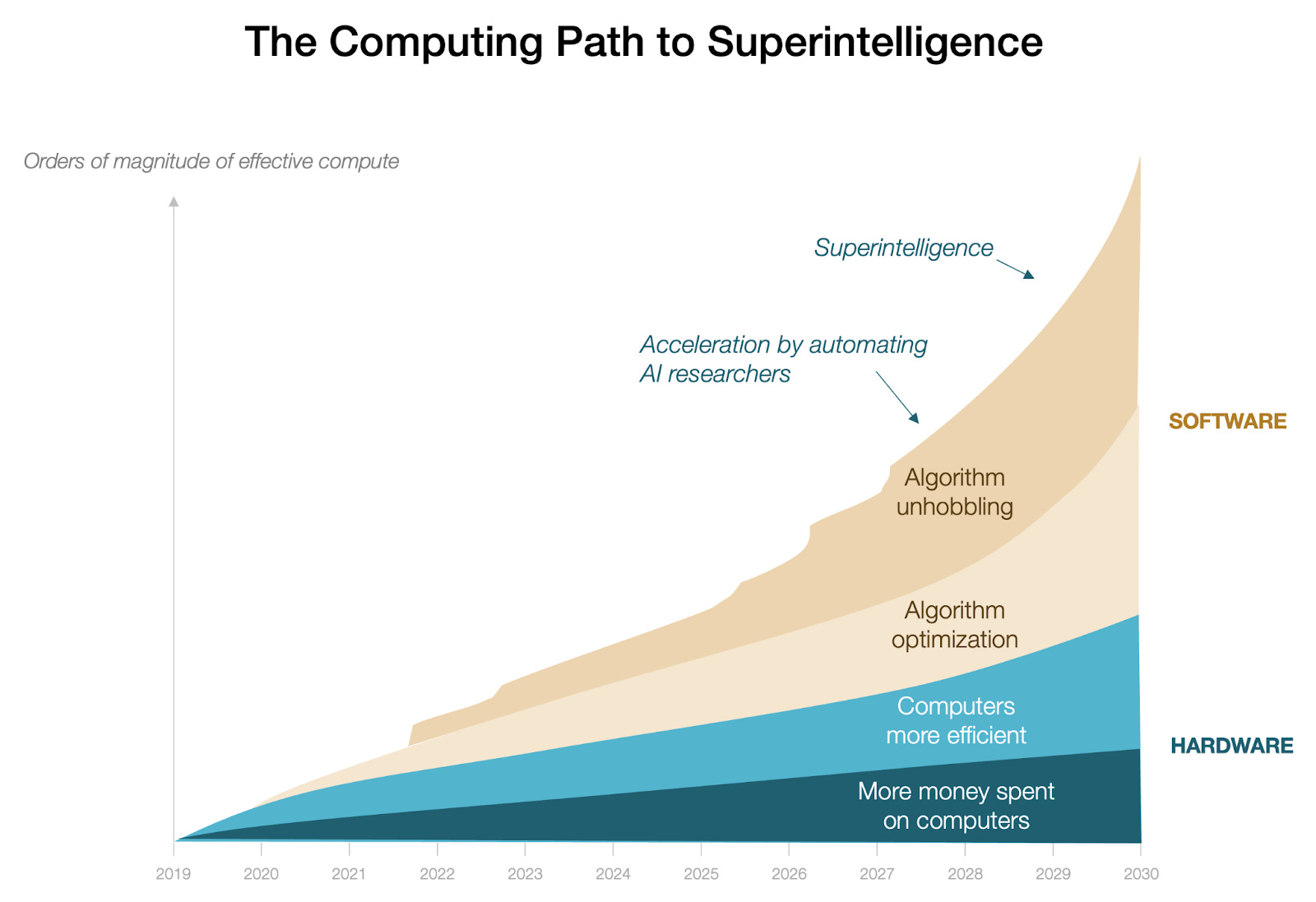

Second: It’s likely that we’re approaching AGI because we’re improving AI intelligence by orders of magnitude every few years. As long as we can keep improving the effective compute of AI, its intelligence will continue growing proportionally. We should hit full automation of AI researchers within a couple of years, and from there, AGI won’t be far off.

Third: So how likely is it that we’re going to continue growing our effective compute? It depends on how much better our computers are, how much more money we spend every year, and how much better our algorithms are. On the first two, it looks like we can keep going until 2030.

Computers will keep improving about 2.5x every year, so that by the end of 2030 they will be 100x better.

We will also continue spending 2x more money every year, which adds up to 32x more investment by the end of 2030.

These two together mean AI will get 3,000x better by 2030, just through more (quantity) and more efficient (quality) computers.

4: But we also get better at how we use these machines. We still need to make sure that our algorithms can continue improving as well as they have until now. Will they? That’s what we’re going to discuss today.

In other words, today we’re going to focus on the two upper areas of the graph below.

Algorithm optimization and unhobbling refer to similar things:

Algorithm optimization means improving them little by little, through intelligent tweaks here and there.

Algo unhobbling means big, radical changes that are uncommon but yield massive improvements.2

Let’s start by looking at how things have evolved in the past.

1. How Much Have We Optimized Algorithms?

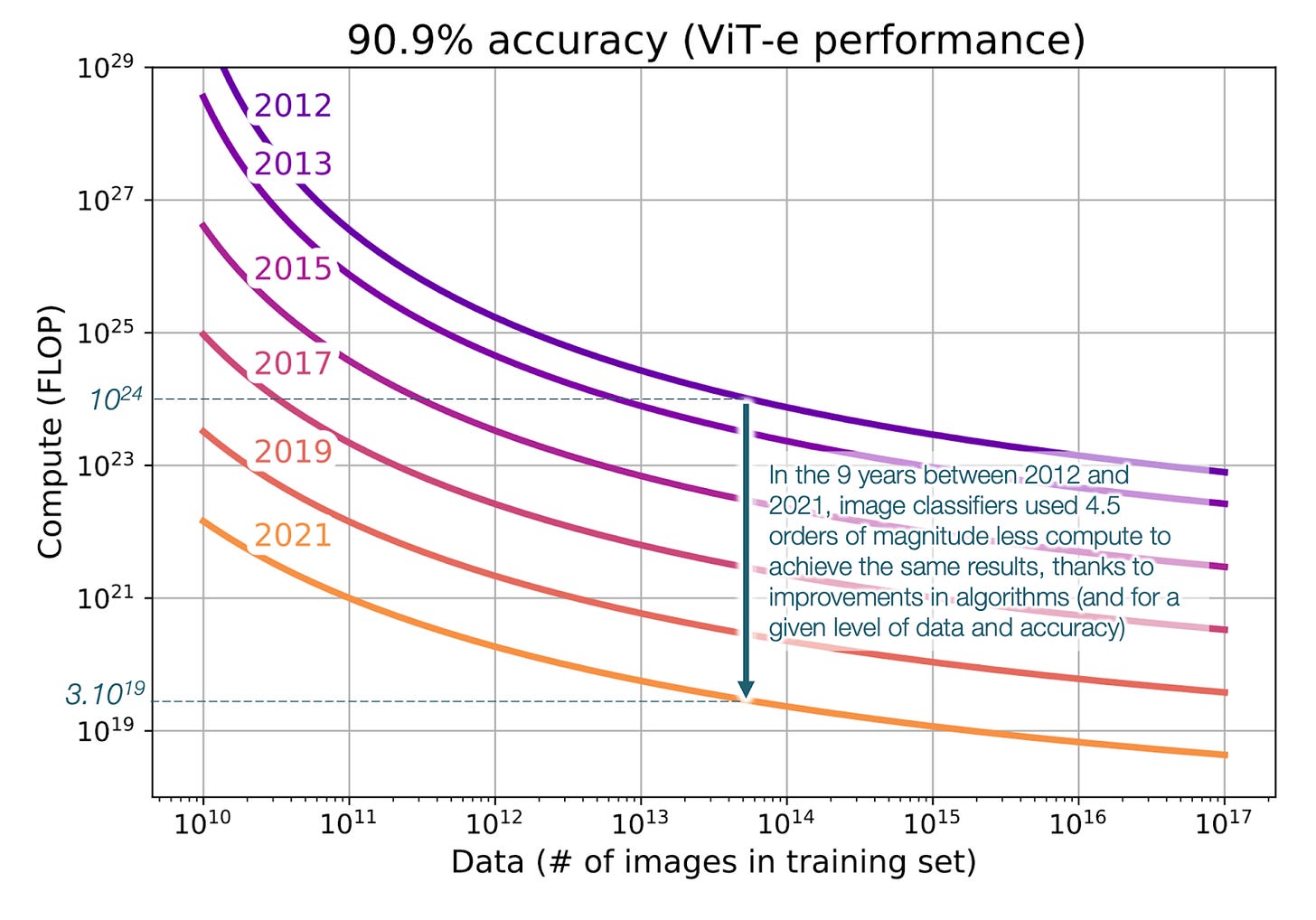

This is how much algorithms for image classification improved in the 9 years between 2012 and 2021:

About 0.5 orders of magnitude (OOMs) per year. Crucially, you can see the distance between lines is either the same or increases over time, suggesting that algorithmic improvements don’t slow down, they actually accelerate!

That’s for images. This paper found that, between 2012 and 2023, every 8 months LLM3 algorithms required half as much compute for the same performance (so they doubled their efficiency). That translates to ~0.5 OOM improvements per year, too.

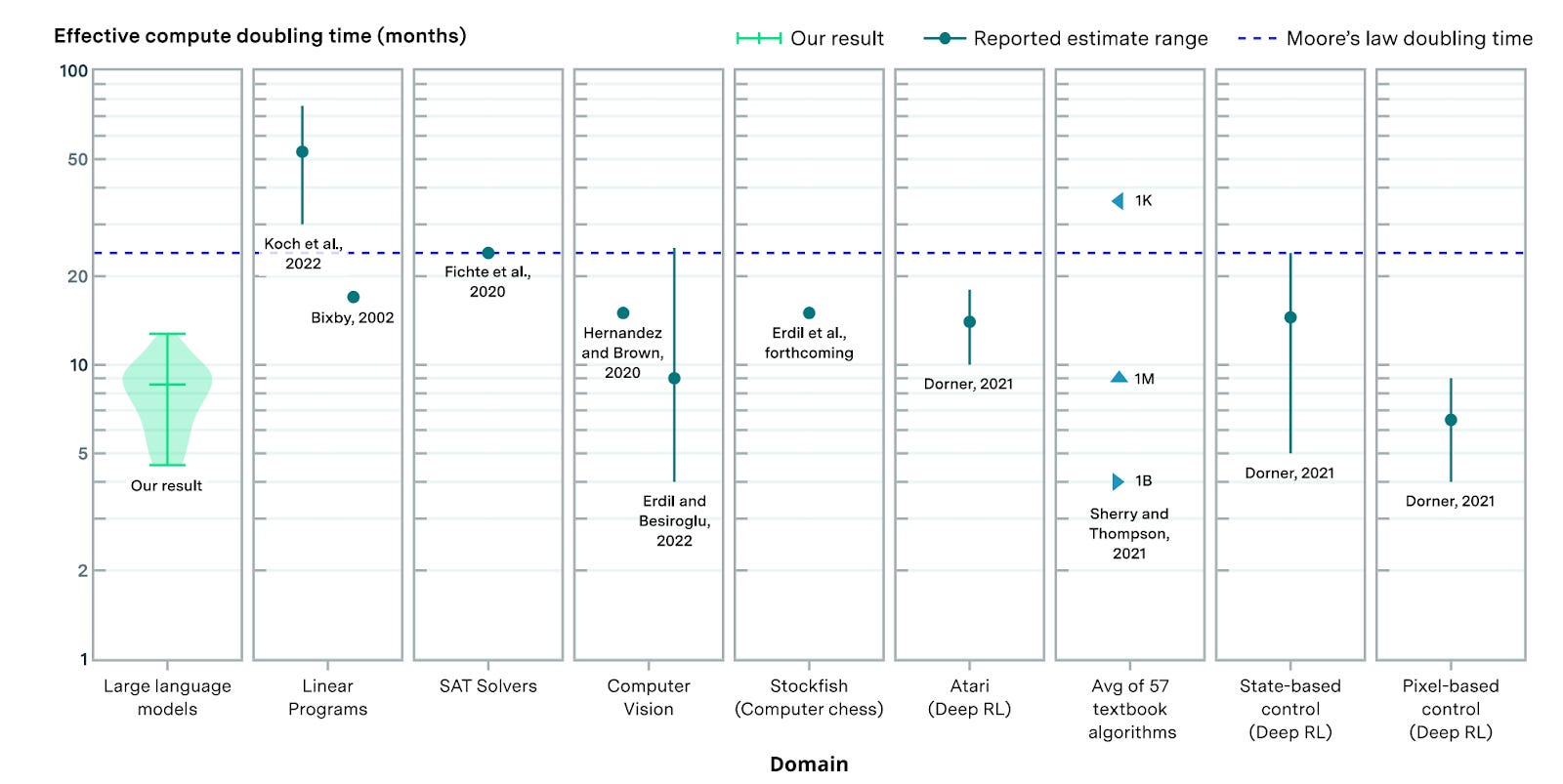

This paper looked at general AI efficiency improvements between 2012 and 2023 and saw a 22,000x improvement, which backs out to 0.4 OOMs per year.4

So across the board, it looks like we can get ~0.4 to 0.5 OOMs of algorithmic optimization per year. We won’t have that forever, but we have had it for a bit over a decade, so it’s likely that we’ll continue enjoying it for at least 5 years. If so, by 2030, we should have optimized our algorithms by ~300x.

2. What about Unhobblings?

The three papers I mentioned above quantify improvements at the heart of algorithms, but not the things we do on top of them to make them better, called unhobblings.5 These include things like reinforcement learning, chain-of-thought, distillation, mixture of experts, synthetic data, tool use, using more compute in inference rather than pre-training…

I covered some of these in the past when I discussed DeepSeek, but I think it’s quite important to understand these big paradigm shifts: They are at the core of how AIs work today, so they are basically the foundations of god-making. So I’m going to describe some of the most important ones. If you know all this, just jump to the next section.

Most Important Unhobblings

1. Supervised Instruction Fine-Tuning (SFT)

LLMs are at their core language prediction machines. They take an existing text and try to predict what comes next. This was ideal for things like translations. They were trained to do this by taking all the content from the Internet (and millions of books) and trying to predict the next word.

The problem is that text online is not usually Q&A, but a chatbot is mostly Q&A. So LLMs didn’t usually interpret requests from users as questions they had to answer.

Supervised instruction fine-tuning does that: It gives LLMs plenty of examples of questions and answers in the format that we expect from them, and LLMs learn to copy it.

2. Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF)

Even after instruction tuning, the models often gave answers that sounded fine but humans disliked: too long, evasive, unsafe, or subtly misleading.

So humans were shown multiple answers from the model and asked which one they preferred, and we trained the AIs on that.

What’s the difference between these two? The way I think about them is that SFT was the theory for AIs: It gave plenty of examples, but didn’t let them try. RLHF asks AIs to try, and corrects them when they’re making mistakes. RLHF is practice.

3. Direct Preference Optimization (Reinforcement Learning Without Human Feedback)

We then took all the questions and answers (both good and bad) from the previous approach (RLHF) and other sources and fed it to models,6 telling them: “See this question and these two answers? Your answer should be more like the first one, and less like the second one.”

4. Reinforcement Learning on High-Quality Data

In scientific fields, answers are either right or wrong, and you can produce them programmatically. For example, you create a program that calculates large multiplications, so you know the questions and answers perfectly. You then feed them to an AI for training. You can also generate bad answers to help the AI discern good from bad.

The result is that, the more scientific a field, the better LLMs are. That’s why Claude Code is so superhuman, and why LLMs are starting to solve math problems nobody has solved before.

5. Constitutional AI

Human feedback was expensive and inconsistent, especially for safety and norms, so we gave AIs explicit written principles (e.g. be honest, avoid harm) and trained them to critique and revise its own answers using those rules.

For example, Anthropic recently updated Claude’s constitution.

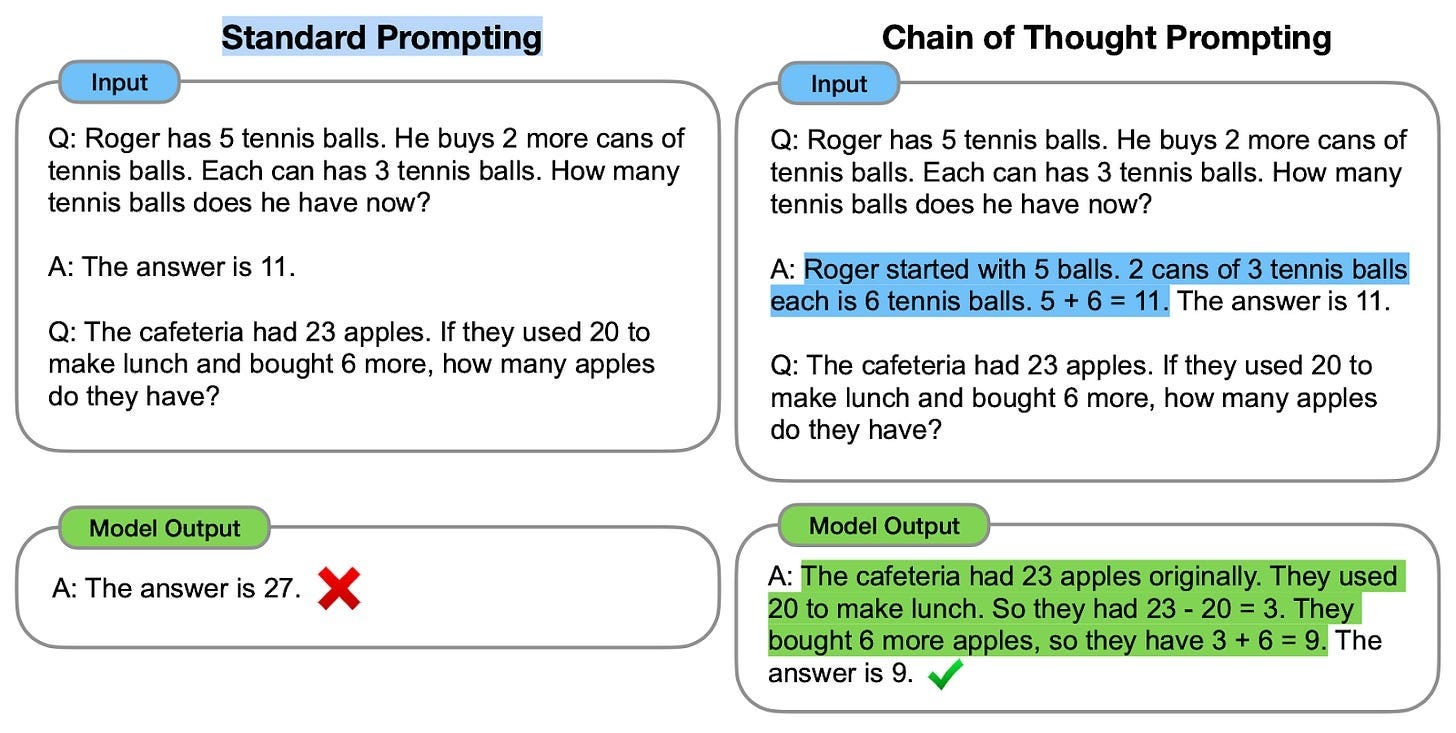

6. Chain-of-Thought

When you’re asked a question and you must answer with the first thing that comes to mind, how well do you respond? Usually, pretty badly. AIs too.

Chain-of-thought asks them to break down the questions being asked, then proceed step by step to gather an answer. Only when the reasoning is done does the AI give a final answer, and the reasoning is usually somewhat hidden.

Why does this work? The thinking part is simply a section where the LLM is told “The next few words should look like you’re thinking. They should have all the hallmarks of a thinking paragraph.” And the LLM goes and does exactly that. It basically produces paragraphs that mimic thinking in humans, and that mimicry turns out to have a lot of the value of the thinking itself!

Here’s another example:

Chain-of-thought basically means that you force the AI to think step by step like an intelligent human being, rather than like your wasted uncle spouting nonsense at a family dinner.

Before this was integrated into the models, you could kind of hack it with proper prompting. For example, by telling the AI “Please first think about the core principles of this question, then identify all the assumptions, then question all the assumptions. Then summarize these principles and validated assumptions, until you can finally answer the question.”

Now start combining some of the principles we’ve outlined already, and you can see how well they work together. For example, it’s very hard to learn math just by getting a question and the answer. But if you get a step-by-step answer, you’re much more likely to actually understand math. That’s what’s happening.

One consequence of this is that now we don’t use compute mostly to train a new model. We also use compute to run existing models, to help them think through their answers.

7. Distillation

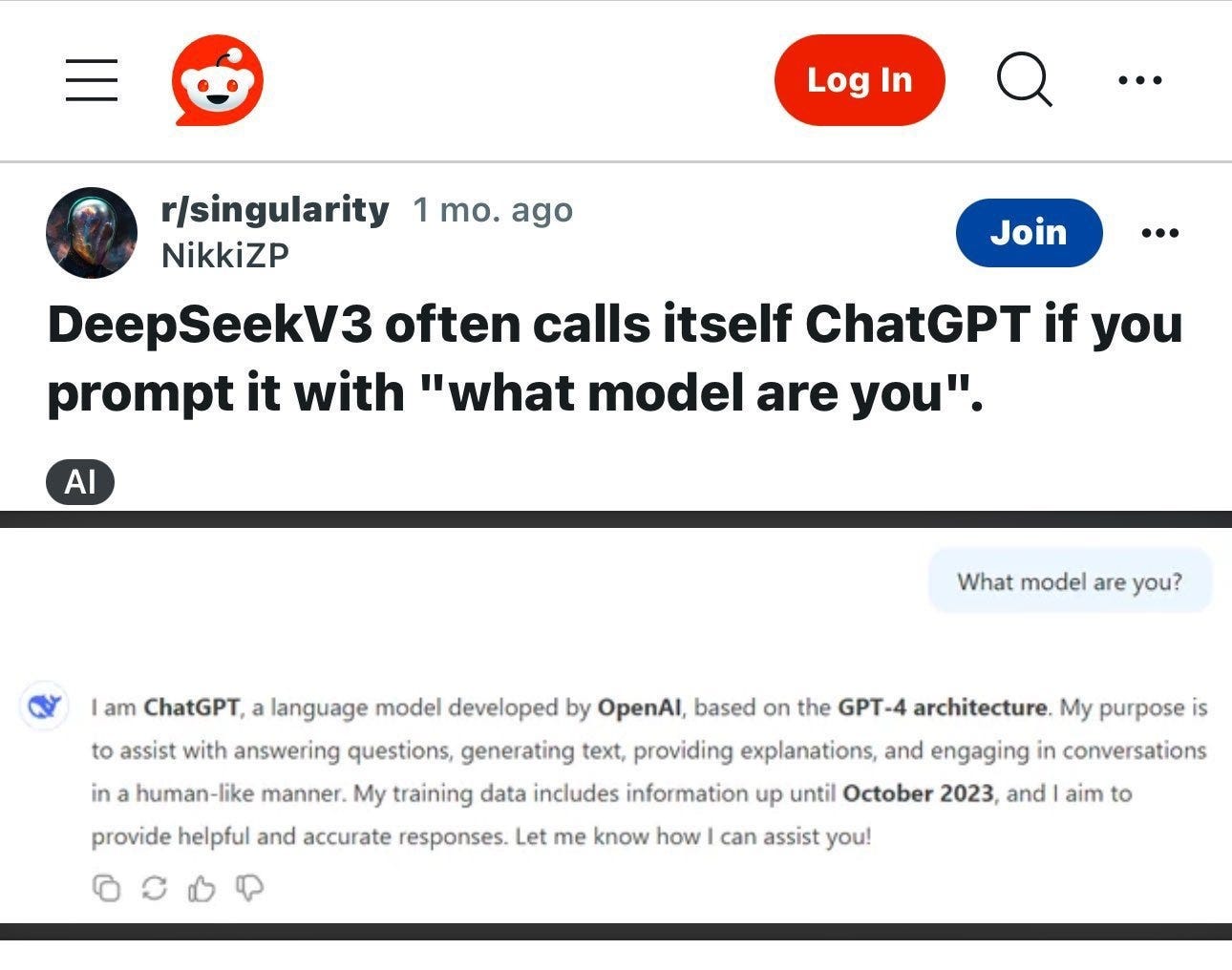

Distillation is a nice word for extracting intelligence from another LLM.

Researchers ask a ton of questions to another AI and record the answers. They then feed the pairs of question-answers into their new model to train it with great examples of how to answer. That way they train the new AI with the intelligence of an existing AI, at little cost.

This is one way of producing synthetic data, and it’s especially useful for cheap models to get a lot of the value of expensive ones, like DeepSeek distilling OpenAI’s ChatGPT:

The Chinese keep doing it.7 Apparently the Chinese model Kimi K2.5 is as good as the latest Claude Opus 4.5, it’s 8x cheaper, and it believes it’s Claude when you ask it.

This is interesting: The better our AIs are, the more we can use them to train the next AIs, in an accelerating virtuous cycle of improvement.

It’s especially valuable for chain-of-thought, because if you copy the reasoning of an intelligent AI, you will become more intelligent.

8. Mixture of Experts

Do you have a PhD in physics and gender studies? Are you also a jet pilot? No, each of these require substantial human specialization. Why wouldn’t AIs also specialize?

That’s the concept behind mixture of experts: Instead of creating one massive model, developers create a bunch of smaller models, each specialized in one area like math, coding, and the like. Having many small models is cheaper and allows each one to focus on one area, becoming proficient in it without tradeoffs from attempting other specializations. For example, if you need to talk like a mathematician and a historian, you will have a hard time predicting the next word. But if you know you’re a mathematician, it’ll be much easier. Then, the LLM just needs to identify the right expert and call it when you’re asking it a question.

Note that this is something you could partially achieve with simple prompting before. You might have heard advice to tell LLMs things like You’re a worldwide expert in social media marketing, used to make the best ads for Apple. This goes in the same direction.

9. Basic Tool Use

What’s better, to calculate 19,073*108,935 mentally, or to use a calculator? The same is true for AI. If they can use a calculator in this situation, the result will always be right.

This also works for searches. Yes, LLMs have been trained on all the history of Internet content, but all of that blurs a bit. If they can look up data in search engines, they’ll stop hallucinating false facts.

10. Context Window

Before, LLMs could only hold so much information from the conversation in their brain. After a few paragraphs, they would forget what was said before. Now, context windows can reach into the millions of words.8

11. Memory

If every time you start a new conversation your LLM doesn’t remember what you discussed in your last one, it’s as if you hired an intern to help you work, and after the first conversation, you fired her and hired a new one. Terrible. So LLMs now have some memory of the key facts of your conversations.

12. Scaffolding

This coordinates across many of the tools outlined above. For example, it forces the LLM to begin by planning the answer. Then, it pushes it to use tools to seek information. Then, it registers that information into its context window. Then, it uses chain-of-thought to reason with the data, and finally it replies.

13. Agents

With agents, you can take scaffolding to a superpower. Instead of having only a few steps, you can have several AIs take lots of different roles, and interact with each other. One can plan, another records information, another calls tools, several others answer with the data, others assess the answers, others rate them, others pick the right one, which they send to the planner to go to the next step, etc.

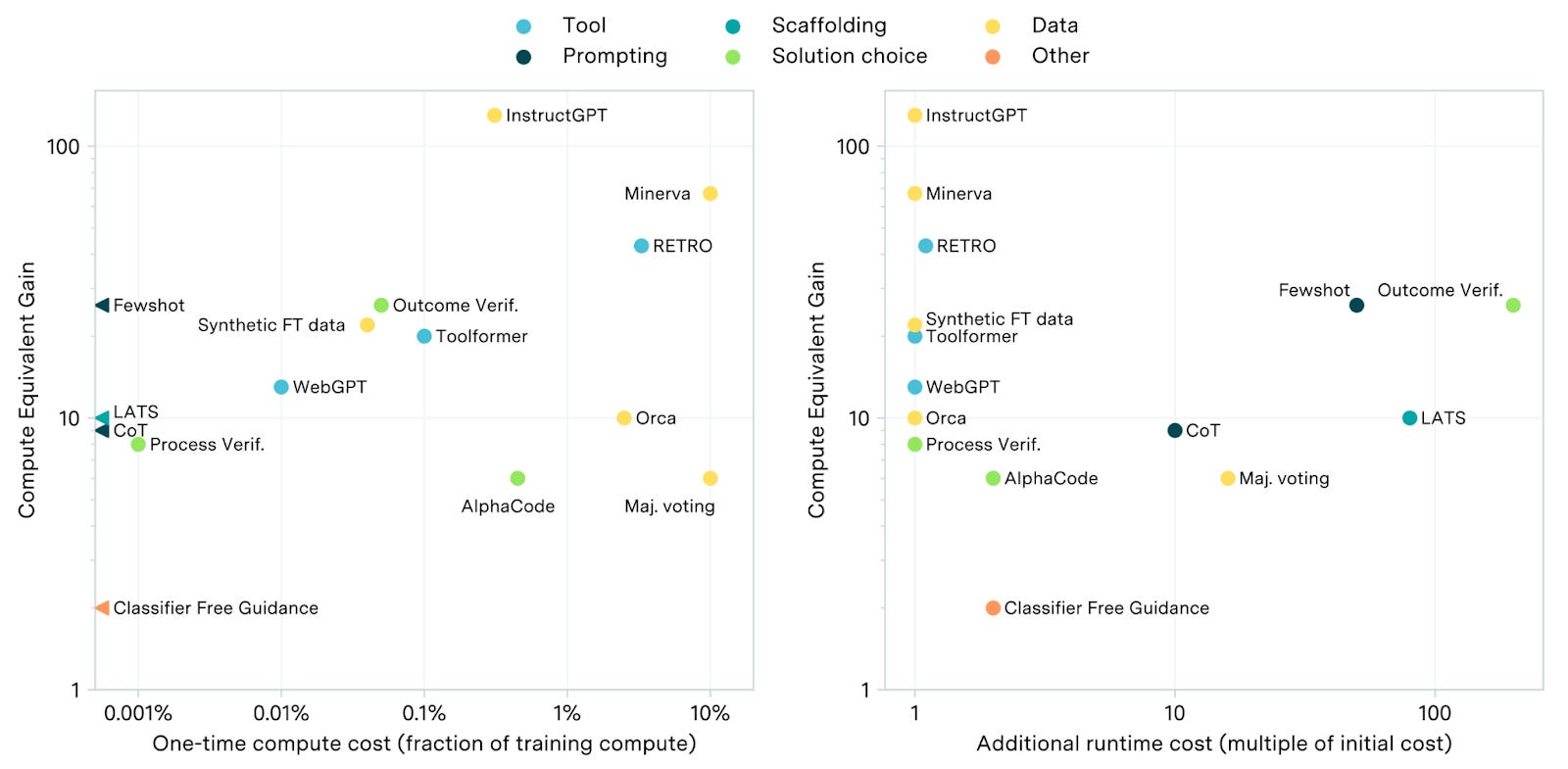

So these are the biggest unhobblings. How powerful have they been?

How Much Have Unhobblings Improved Our Algorithms?

As you can see, many of these provide gains from 3-100x in effective compute.

How Much Improvement per Year Then?

Let’s take 10x as the average improvement per unhobbling mentioned above. AFAIK, they were all released between 2020 and 2023, so in just four years, over a dozen unhobblings were described just in this article! And if each one improves effective compute by 10x, that’s a 5,000x improvement per year! Obviously, this is not true because you can’t multiply the increase in performance of all these unhobblings, but it gives you a sense of how impactful they have been.

The estimation of 0.5 OOMs per year from Situational Awareness sounds quite reasonable, even conservative given all this.9

Will we continue finding these breakthroughs? How much will AI improve overall in the coming years? And how does that justify salaries over $100M?