Can Brazil Become a Superpower?

How Brazilians Persevere Against Geographic Adversity

Welcome to this week’s free Uncharted Territories article. Here are the premium articles you might have missed this month:

Is the Amazon Rainforest in danger? How? Why? Can it disappear?

How to gain an advantage by incorporating information immediately.

What prevents cities from building up and increasing density?

How transportation technologies spread humankind and limited the sizes of empires.

Subscribe to get access to these posts, and every post.

Now, onto this week’s free article!

“We’re arriving at Rio de Janeiro’s airport. Please prepare for landing.”

You eagerly look out the window and gorge on the breathtaking view.

As you step out of the plane, the warm, humid air invades your lungs; you pull on your shirt to separate it from your skin. The sun blinds your eyes; you instinctively reach for your sunglasses.

This experience encapsulates Brazil’s strengths and weaknesses.

There are few places in the world where the mountains, the beaches, and the jungle clash in such a striking way. This has determined Brazil’s situation to this day.

Look at a map of South America.

Brazil takes up half of that.

There are immediately two parts of the country that pop out: the Amazon rainforest in the northwest, and a mountainous region in the southeast, the Brazilian Shield—also called the Brazilian Highlands.

I covered the Amazon in last week’s premium article:

Some crazy facts about the Amazon Rainforest, river, and river basin.

The old civilizations that lived there.

Why it’s so hard to develop it.

Is it being deforested?

Is it at risk of disappearing?

Later this week, I’ll cover other aspects about Brazil in another premium article. But today we’re going to focus on the other piece, the Shield. Why?

Between the Shield and the Sea

This is the population density of Brazil:

As you can see, virtually everybody in Brazil is close to the eastern coast. Only 11 million Brazilians live in the Amazon river basin, out of a total of 217M. 87% of Brazilians live in the highlands or the coast.

The images of Brazil that international audiences usually see are mainly those of the rainforest1, but this is not the reality of Brazilians. They live in the Brazilian Shield or on the coast between the Shield and the Atlantic.

The biggest part of the Shield is O Cerrado.

O Cerrado

O Cerrado is a savannah, because it’s on tropical land but elevated. The result is this type of terrain:

Since it’s in the tropics and close to the ocean, it gets a fair amount of rainfall. But it’s very rugged. And if that was not enough, the soils are also poor…

The rains have leached this soil for eons, carrying its nutrients with the water and into the ocean. It doesn’t have lots of nutrients left, so it’s not very fertile. For Brazilians to use this land for agriculture, they must do so with brute force: They must clear it, level it, and fertilize it.

This is exactly what Brazilians have been doing:

The Cerrado was thought challenging for agriculture until researchers at Brazil's agricultural and livestock research agency, Embrapa, discovered that it could be made fit for industrial crops by appropriate additions of phosphorus and lime. In the late 1990s, between 14 million and 16 million tons of lime were being poured on Brazilian fields each year. The quantity rose to 25 million tons in 2003 and 2004, equaling around five tons of lime per hectare. This manipulation of the soil allowed for industrial agriculture to grow exponentially in the area. Researchers also developed tropical varieties of soybeans, until then a temperate crop, and currently, Brazil is the world's main soybeans exporter due to the boom in animal feed production caused by the global rise in meat demand.—Source, emphasis mine.

This is the region that has seen the most investment in agriculture in Brazil, not the Amazon2. So when you hear that Brazil has been clearing lands for agriculture, as a rule of thumb it’s in this region, clearing savannah, not rainforest.

Indeed, about 40% of its land has been converted to agriculture, and another 40% is used for charcoal. Only 20% remains intact.

Once you’re done with the terraforming, you need to connect all this land with the rest of the world to sell your products. In most countries, you can do this with rivers. Not in Brazil:

Rivers are not that useful in Brazil:

The Amazon is the only navigable river, but as we saw it only serves a few million people, and less than 10% of the Brazilian GDP3.

The Paraná, Paraguay rivers (green in the south in the river basin map above, because they both merge into the Rio de la Plata in Argentina) and the Uruguay river (purple, at the bottom) are all navigable, but not in the Brazilian portions4.

The coast has a bunch of small rivers that go through rugged terrain. They are not navigable.

Instead, most of the water close to the coast flows inland! That creates big river basins like those of the São Francisco river, but because the terrain is so rugged, none are navigable5.

This is what the São Francisco river looks like in Alagoas, close to its end in the Atlantic ocean.

This is a terrible geography for the Brazilian economy: No navigable rivers plus rugged terrain means extremely high transport costs. You can’t transport anything by water—which is 10 to 30 times cheaper than by road.

Your only option is to transport it by road. And indeed, Brazilians have structured their country around their roads. Look at this map of night lights against the topography:

We can see the population density on the coasts, especially on the southeast. But what we can also see are lines of dots.

As we’ve discussed in Why Cities Thrive, cities follow transportation lines. In the São Paulo region, it’s very obvious that these are roads.

The same is true for the broader Brazil.

But building roads is expensive, and building roads across millions of kms of rugged terrain is even more expensive.

So after clearing, leveling, fertilizing, and sowing their rugged fields, Brazilians had to communicate them with the world, so they’ve been spending billions painstakingly building roads.

But as we saw, road transport is much more expensive than river transport, so a big share of the value of these crops goes to transport rather than Brazilians’ pockets, which means less money to invest in the roads in the first place. The result is few roads, fewer highways and railroads, expensive transport costs, lower agricultural margins, and more poverty.

One of the ways of improving these economics is by shipping stuff that is more valuable per ton. It’s one of the reasons why Brazilians have invested in more valuable crops where they could, or converted some crops into meat.

Even then, Brazil’s exports are still very focused on raw materials, which don’t capture a big chunk of the value chain6, and are more expensive to export from Brazil than from most other countries. This accentuates the issue: Lower margins, less capital to invest, less infrastructure, and less growth.

Most countries with a rugged core benefit from dynamic coastal regions. But Brazil’s geography has a problem that prevents it from doing that.

The Great Escarpment and the City States

This is São Paulo, seen from the coast.

On the coast, you have a small plain where the port city of Santos stands. Immediately after, the highlands start with the Great Escarpment. Zooming in:

São Paulo is just 30km away from the coast7, but it’s nearly 800m high! Compare that with the Mississippi, which can be navigated up to Minneapolis, which is just 200m high and 3,000 km inland. All the land from there to New Orleans can benefit from navigable rivers to ship what they produce. São Paulo can’t do the same even if it’s a stone’s throw away from the ocean!

To give you a sense of the engineering complexity:

São Paulo must transport everything through a couple of roads to its port city, Santos, which is shoehorned into a tiny coastal plain. Santos has no place to grow, and its port is not that big, meaning that São Paulo’s gate to the world is small, expensive, and crowded.

And by Brazilian standards, São Paulo is lucky. It sits on a plateau, so the city and its hinterland are quite flat, so it’s cheap to build and cultivate. That’s why the entire state of São Paulo has the roads we saw in the nightlights, and why it hosts 44 million people, half of whom live in the city proper. So São Paulo’s state accounts for 20% of the Brazilian population but a third of its GDP.

The next state in terms of GDP is tiny Rio de Janeiro.

The state of Rio de Janeiro is small because 85% of its population lives in the Greater Rio de Janeiro city (about 14M people), which is just a coastal city stuck between the Great Escarpment and the ocean. Rio is where it is because it’s one of the biggest coastal plains on Brazil’s coast. For most other cities, having huge mountains in the middle of a plain would be a big issue. For Brazil, that’s not a problem: At least there is a plain!

So when you see images of vertical favelas, that’s the consequence of living in a small, narrow, shoeboxed plain sprinkled with towering mountains. There’s just nowhere else to go.

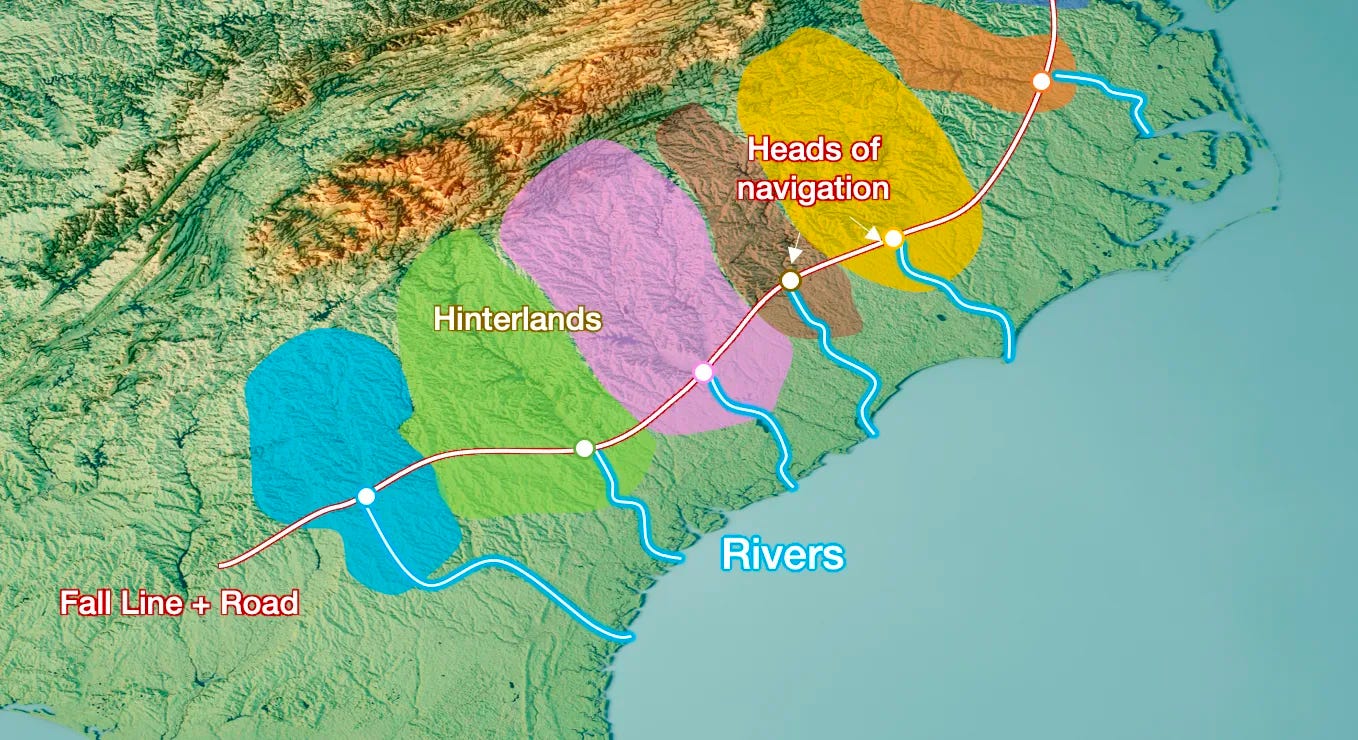

In my previous articles about cities, I’ve highlighted how cities tend to appear: They’re on lines like rivers or coasts, connecting their hinterland to the rest of the world. Then they build infrastructure to further that connection. The more connections, the more they grow, the more the cities and their hinterland become rich. For example, on the US Eastern Seaboard.

Unfortunately, Rio has none of that. It’s disconnected from the rest of the country due to the Great Escarpment. Its growth is limited to its coastal plain. It has no hinterland that it can connect to the rest of the world. It can’t benefit from neighboring cities with which it merges. Its infrastructure doesn’t benefit anybody else, so nobody else can chip in to build it. Why would it build a massive port? To ship whose products? And it has no rivers to make all of this easier. It’s really just a city state.

This is the story of nearly every big coastal city in Brazil. They’re all stuck between the Shield and the Sea.

And that’s why most of them have mountains in the city or just behind.

Since none of these coastal cities are well connected to a rich hinterland, none of them have a lot of money to make from trade, they can’t afford to build great infrastructure, and the vicious circle continues8. The result is that the top seven Brazilian ports combined have less loading capacity than New Orleans. All these cities are closer to city states than to big, integrated metropolises.

This picture from the International Space Station shows all these patterns well:

You can see:

São Paulo, the biggest blob in the center, close to the coast.

Santos, close to it, on the coast.

The lines of light converging towards São Paulo, along the roads, showing São Paulo’s hinterland.

The road leading to Rio de Janeiro, the big blob of light on the coast.

The blobs of light along the coast, completely independent from each other.

The mountains of O Cerrado and the Shield.

If the Cerrado can’t generate much wealth and the coastal cities are a bit secluded, how can Brazil grow its wealth? There is the São Paulo region, and south and west of it, the country is reasonably fertile.

Alas…

The rivers Paraguay, Paraná, and Uruguay all flow into the Rio de la Plata. The sources of all three rivers are in Brazil. All three valleys are quite fertile, so agricultural yields are good there. And all three are navigable… outside of Brazil—in the countries of Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina. This is quite bad for Brazil:

It doesn’t get the benefits of cheap trade through the rivers.

Its neighbors do, which means much better, cheaper trade for them.

Watersheds tend to merge into economic zones, because it’s much easier to trade and communicate with the people who share the same valley than those on the other side of the mountains. If on top of that you can trade with them via the river, the unity is even stronger.

These rivers are so valuable that the countries of Paraguay and Uruguay are named after their respective rivers. The word Argentina comes from the Latin for silver, while Rio de la Plata is named after the Spanish word for silver. All three countries are built around these rivers. Their borders are mostly drawn by the rivers9.

This river basin wants to unite, and whoever controls it is the most powerful country in the region. That’s why Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia all went to war several times after their independence from Spain and Portugal: They all knew that whoever controlled the region would become wealthier.

Since this part of Brazil was so hard to access from the rest of the country, Brazil was at a disadvantage fighting these wars. That’s why it lost first Uruguay, and then all the navigable parts of these valuable rivers. This region of Brazil was stuck, landlocked, while the economies of neighboring Paraguay and Argentina thrived.

The bloodiest war, the War of the Triple Alliance, saw landlocked Paraguay attacked by an alliance formed by Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Between 25% and 60% of Paraguayans died, and Paraguay lost a big chunk of its territories.

The winner of all of this was Argentina, who owns the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, and made Uruguay and Paraguay into Rio de la Plata satellite countries.

Brazil, meanwhile, is left with the unnavigable pieces of these rivers, but these valleys are nevertheless closer economically to its neighboring Rio de la Plata countries than to the rest of Brazil: It’s easier to trade with that region and build infrastructure to ease that trade than building roads across the mountains. The result is a rich region that pulls away from Brazil rather than make it more cohesive.

Add to that the independence of the coastal city states and the Amazon rainforest, all of them poorly connected, and you get a patchwork of states rather than a nation-state.

The Geoeconomic Trap

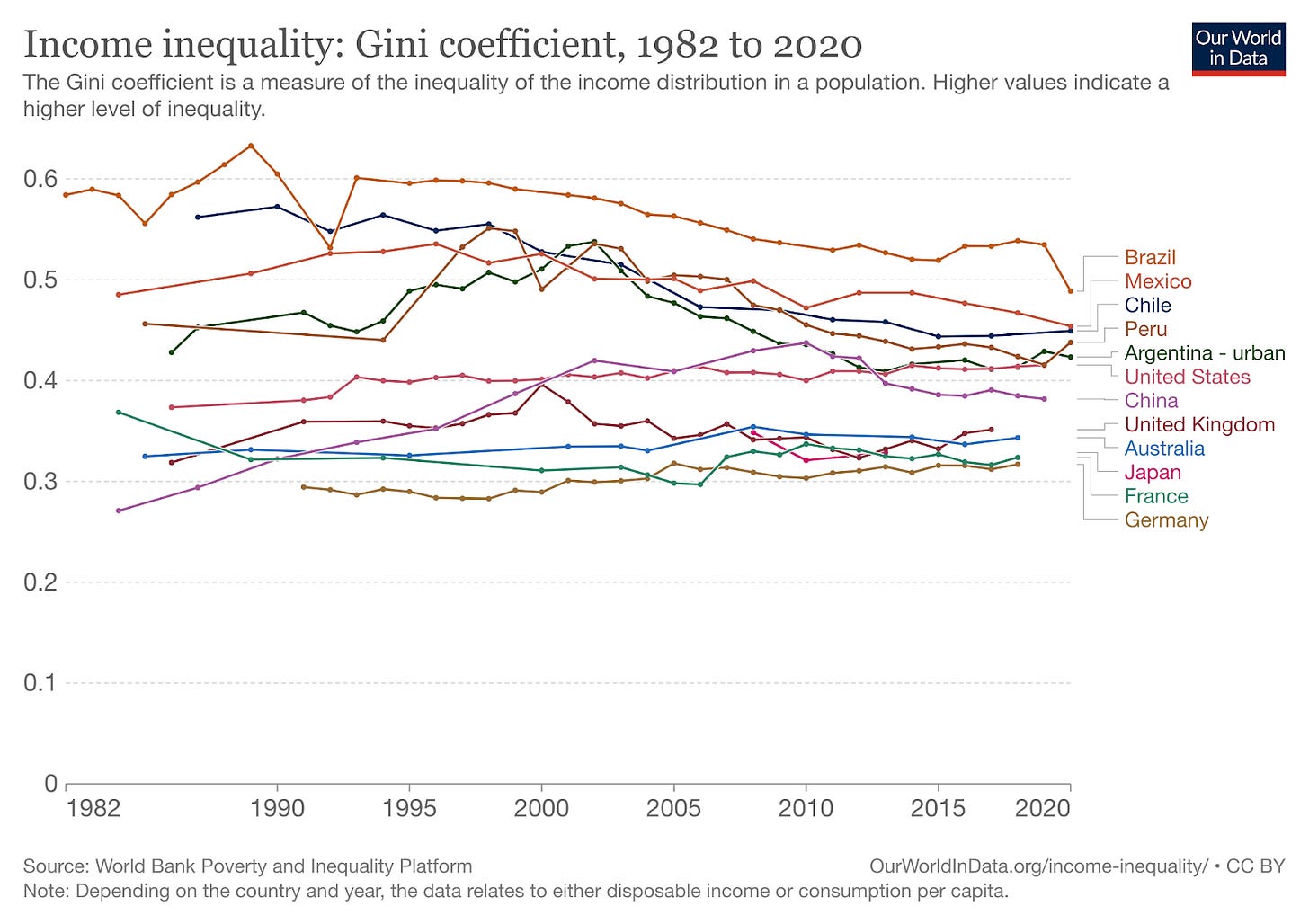

All of this has challenged Brazil’s growth. For example, inequality.

Brazil is still a very high inequality society.

Investment

Given all the issues with Brazil’s geography that we’ve mentioned above, the country needs massive investments in infrastructure and land management to develop. This takes so much money that it was historically impossible for small farmers to set up shop like in the US. But the government couldn’t afford this either, because given these costs, margins were not big enough to generate much taxable wealth.

Only big private capital owners could do it. This is true not just for traditional highly capitalized enterprises like mines. Every farm and road requires big investors to finance them. These investors then own these assets and their profits. This has led Brazil to be a very unequal society. But it’s not the only factor that has driven inequality.

Crops vs Human Capital

Before all this investment, standard crops like rice, wheat, barley, or corn could hardly grow in Brazil. Instead, the only thing that grew without expensive land management were tropical plantation crops like tobacco, sugar, bananas, coffee, or citrus.

But crops like wheat or corn don’t need much work, and small rice paddy fields can be handled by small families. In contrast, these tropical crops need a lot of unskilled processing. For example, coffee beans need to lose the skin, pulp, mucilage, and parchment, for which they must be washed, deskinned, fermented, washed again, dried… Tobacco is even more complex. The result is that Brazil was the biggest client state of slavery in the Western world, with a full 40% of African slaves shipped to the country. This dependence is why Brazil was the last Western country to abolish slavery.

All this unskilled, manual labor was placed in corporate plantations, not cities with a strong middle class that could invest in education. The result is that Brazilians, to this day, have a low level of educational attainment.

Inflation

If you have little quality land that is easily available, little capital to invest, and a low level of skilled labor, you have little of everything that it takes to grow as a country. And the moment you grow a bit, you run out of land, skilled labor, or capital, and prices go up. The result is high inflation.

This inflation is tricky, because it appears the moment the country is growing fast.

Inflation happens when there’s a lot of demand for something, but not enough supply, and the supply is constrained. For example, during COVID, suddenly everybody had cash and wanted to spend it on things like cameras for the computer or weights to do exercise at home. But it wasn’t easy to increase the capacity to provide more of these, and China was locked down, so it couldn’t produce or ship more of these types of items. More demand and constrained supply meant inflation. A typical inflation scenario is also when governments print money, because suddenly people have lots of demand (in the form of paper bills) and are trying to buy things that can’t magically be produced as fast as the printing machine.

In Brazil, everything is scarce.

Quality land in Brazil is scarce, so when suddenly there’s growth and people want to buy land, there’s not a lot of good land available, so buyers bid against each other and the price of land goes up.

Capital in Brazil is scarce, so when lots of entrepreneurs see great opportunities to invest and grow, they will compete for the same capital. Those who have the money (banks, investors) will ask for exorbitant interests, unreasonable conditions, or simply not lend. These entrepreneurs, faced with these steep costs of capital, might not be competitive internationally.

Skilled employees in Brazil are scarce, so when there’s an economic boom, lots of companies will compete for the same talent pool, their salaries will go up, the companies’ margins will go down, along with their international competitiveness.

This is even worse in Brazil because most of what Brazilians export is denominated in dollars: iron ore, oil, soybeans, corn, coffee, sugar… When there’s a commodities boom, the prices of these goods skyrockets. The Brazilians who export these products will make a lot of money. They will try to expand their production, so they will start outbidding each other for scarce capital, land, and skilled employees, and inflation will skyrocket. So even without Brazil doing anything, it can suffer from sudden spurts of growth and inflation.

Decentralization

And if all this wasn’t enough, so much internal geographic division across coastal city states, Amazon rainforest, internal mountains, and the Rio de la Plata river basin, means that Brazil has never had a strong, cohesive, central government backed by the feeling of a nation.

Conclusion: The Future of Brazil

Brazil’s geography is a challenge for growth:

It has many parts completely different from each other.

Its economic core is made up of rugged terrain that needs a massive amount of investment to make it fertile.

Most of its main cities are in small coastal plains that are not in communication with each other or their hinterlands, which limits their ability to grow and invest in infrastructure.

Without rivers, it’s forced to build roads, which are very expensive.

Even then, transportation costs are still high, so the country can’t build capital.

The result is that those developing the country are those with capital, which leads to economic inequality.

Since they didn’t need skilled labor, and they created corporate plantations as opposed to cities, Brazilians in general are poorly educated to this day.

Lack of quality land, good infrastructure, capital, and skilled labor means every time the country grows, inflation soars.

The different regions of this rugged country, plus the oligarchic nature of the economy, mean that political unity has been hard.

This is why it’s so well encapsulated by the geography of Rio, a city-state stuck between the ocean and the Brazilian Shield and its Great Escarpment, with little infrastructure and a small hinterland.

But all of these problems are surmountable. Building roads and fertilizing land is expensive, but Brazil has been doing it, and now it’s reaping the benefits. The country has been growing in population and wealth.

Over time, as the country connects internally, its regionalism subsides.

Even beyond its borders, Uruguay and Paraguay have moved closer to Brazil, taking advantage of an ever lethargic Argentina—I will soon write about Argentina.

As all this happens, Brazil has learned to mostly tame its inflation, and its inequality is going down, while educational levels are going up.

In other words: Most of Brazil’s biggest geographic challenges of the past are being painstakingly surmounted.

This makes Brazil a middle income country.

But it doesn’t make it a rich one.

Brazil’s wealth is its commodities. For it to grow past that, it needs other assets. But it’s going to be incredibly hard for it to beat other countries with industry, because its costs are so much higher than elsewhere. And given its historic protectionism, its local industries are not very competitive.

What alternatives does it have? How can Brazil escape its geographic middle-income trap?

Does it have other ways of becoming a global superpower? What will it take?

More importantly, why is Brazil so huge compared to all its neighbors?

What about some other Brazilian quirks? For example, why is Brazil home to the largest Japanese population outside Japan?

I will answer these questions and more in this week’s upcoming premium article. Subscribe to read it!

And if you want to read the one about the Amazon, here it is.

Or Rio.

As we’ll see in the Amazon article later this week, if making the Cerrado viable agriculturally is expensive, it’s even worse for the Amazon rainforest.

The heads of navigation of the Amazon are Manaus and Iquitos, depending on the size of the ship. If you follow Uncharted Territories, you will know that it is not a coincidence that the heads of navigation are also big cities: Manaus and Iquitos probably grew because of that.

The head of navigation of the Paraguay river is Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, the country —again, not a coincidence. The head of navigation of the Paraná is Itaipu Dam, again in Paraguay. The head of navigation of the Uruguay river is Salto, inside Uruguay, the country.

The big purple one is Tocantins Araguaia, the blue one is São Francisco, and the red one is Parnaíba.

Selling iron ore is bad for your economy. Brazil could transform it into steel, for example. That would add some value. It could then turn it into small parts. Or bigger parts. It could combine these parts into more complex elements. Every piece of work made on top of the raw material adds value, so if Brazil did it internally, it would keep that value and be richer. It does some of it—look at the semi-finished iron, steel ingots, pig iron… But Raw iron ore accounts for more exports than all these derivatives combined.

As the crow flies

As we saw, the only city with a developed hinterland is São Paulo, which brute-forced it with roads on its plateau. But it’s disconnected from the rest of the world because of the Great Escarpment and the limits to Santos’ growth.

The Uruguay river draws the borders between the countries of Argentina and both Uruguay and Brazil. The Paraná and Paraguay rivers draw close to half of the borders between the country of Paraguay and both Argentina and Brazil.

I’m Brazilian and you certainly did an outstanding view of Brazil. Congrats

Minor correction: the masculine article in Portuguese is "O" not "El". Thus "O cerrado"