Quarterly Update Q2 2023

Here’s this quarter’s update, where I share all the news that is relevant to past articles we’ve covered together. This time, we’re going to touch on these topics:

Remote Work

Loneliness Epidemic

Better Social Interactions

Brazil and the Amazon

AI is Killing Jobs

The Map is the Territory

More Ocean Currents Subverted

The Economist on Masks

Earthly Winds

Premium from here:

English Density

Viking Expansion

India’s Topography

Why Cities Thrive on the US East Coast

Pakistan Floods

Russian Population Map

English as a 2nd Language

Ciudad de Mexico and Its Lake

Sargassum Beach

Germany’s Nuclear Power

Before we start, here’s a reminder of the articles since last quarter:

AI Series

When Will AI Take Your Job?

How Fast Will AI Automation Arrive? (premium)

Can We See the Impact of Automation in the Economics Statistics?

Automation: Fear of the Past, Economists’ Mistakes, and More (premium)

Infinite Intelligence Solves Most Problems

Future Humans Are Sporadic Indulgences (premium)

Space Series

What Is the Best Real Estate on Mars?

Understand Mars’s Surface Better (premium)

Starship Will Change Humanity Soon

No Room for Deep Space (premium)

Seafloods Series

The Megaflood that Created the Mediterranean

Was There a Mythological Flood? (premium)

Seaflooding

Seaflooding: Past Experience and Future Plans (premium)

Cities Series

How Chicago Became So Huge

The Rise and Fall of Pittsburgh (premium)

Geography Series

Maps Distort How We See the World

Are Maps Deceitful? (premium)

Why Are Tropical Waters Dead, and Can They Kill Europe?

Fascinating Facts about the Oceans (premium)

COVID Series

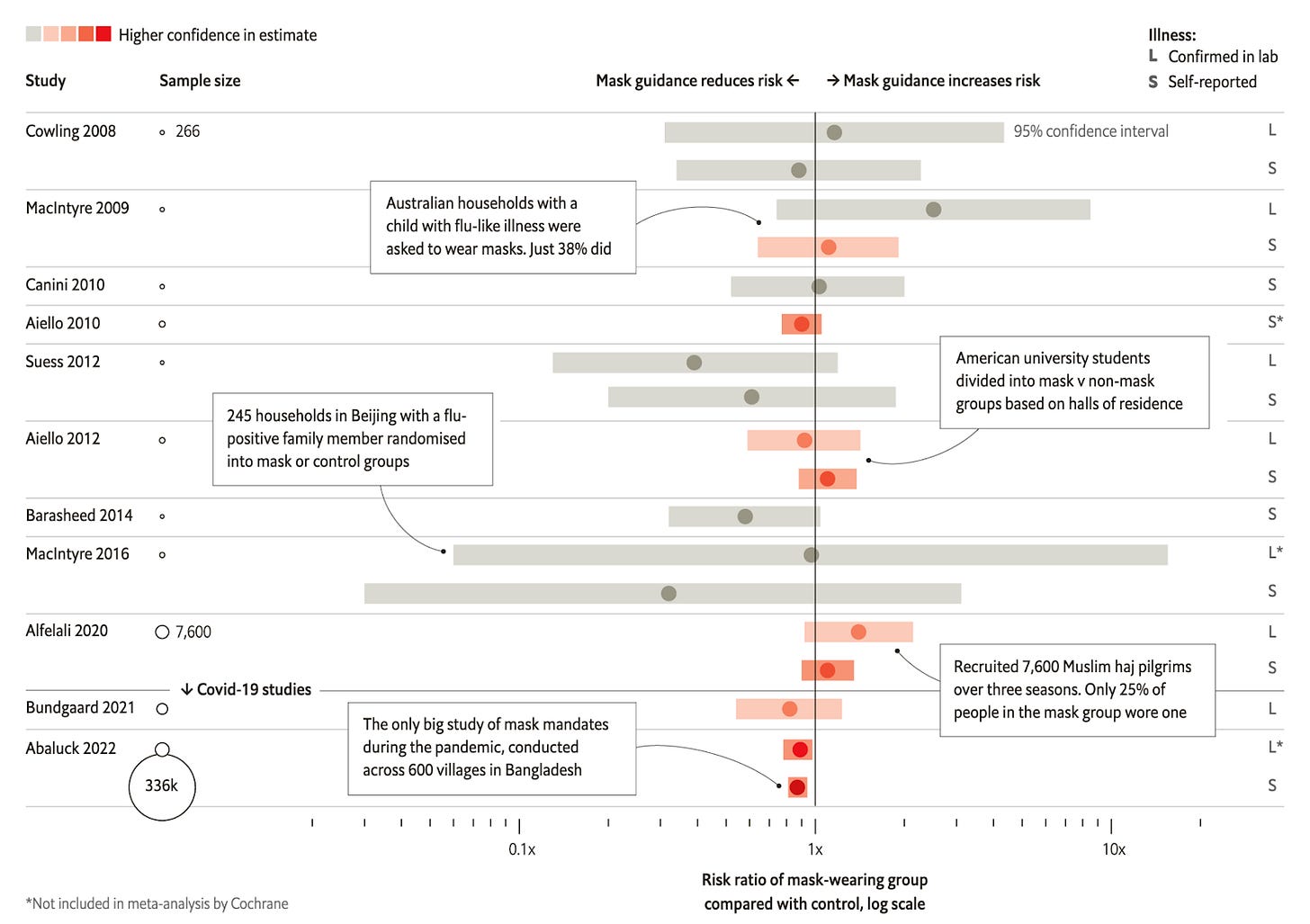

Do Masks Work?

Masks Follow-Up: How to Fight Biases (premium)

OK, let’s get to it!

Remote Work

I’ve touched on it here, here, here, here, here, and here. It’s one of the defining changes of modern lifestyle, so I’ll keep talking about it.

An office building that sold for $300M a few years ago in San Francisco is now worth $60 M.

That’s because vacancies in the city are near an all-time high:

With the massive growth in remote work, more and more people are exploring the nomadic life:

All this is happening as some companies realize they’re more productive online. And, more importantly, that it’s the only way to attract top talent. It might not be a coincidence that the investment bank Credit Suisse forced its employees to come back to the office, while its competitor UBS didn’t. Earlier this year, Credit Suisse folded and was bought by UBS.

But remote work is not superior in every way to office work. For example, a recent paper shows that meeting in person is a catalyst for innovation, and that adding non-stop flights between two cities increases patenting and collaboration in those areas, especially for firms with offices in both places. This effect of flights works best when bridging time zones and big cultural differences. And direct flights also increase the productivity of startups and the returns of their investors.

This begs the question: what is remote work good for, and where does it fail?

Meta (ex-Facebook) has an opinion:

Our early analysis of performance data suggests that engineers who either joined Meta in-person and then transferred to remote or remained in-person performed better on average than people who joined remotely. This analysis also shows that engineers earlier in their careers perform better on average when they work in-person with teammates at least three days a week. This requires further study, but our hypothesis is that it is still easier to build trust in person and that those relationships help us work more effectively.—Meta

Meanwhile, it looks like younger employees are penalized by remote work, because they can’t be colocated with more experienced people to learn from.

From what I’m hearing on this topic in the tech community, it looks like remote work is ideal for deep work: it reduces wasted time commuting and distractions. It’s also especially good for parents, who can combine work with the requirements of raising young children.

Meanwhile, office work is ideal for collaboration, for strategizing, and for quickly learning from peers. It also allows us to create deeper human bonds.

What this suggests is that we’re going to converge toward a world where most knowledge work is done remotely, with people gathering every now and then to discuss strategy, get to know each other better, and share learnings. Maybe by traveling to offsites once a month or a quarter with some type of in-person apprenticeship. This is what long-term remote companies already do.

This also means that we will need remote work tools to allow better strategizing, knowledge sharing, and human connection. As you know, I’m a big proponent of games for the human connection part.

Loneliness Epidemic

The Surgeon General of the US, Vivek Murthy, released in May an advisory on the loneliness epidemic. This is not an epidemic, as premium readers know (read article here). The advisory makes the same mistake as many others, equating aloneness with loneliness. The truth is we’re more alone than ever, but we’re not lonelier. Arguably, we’re as lonely as or less than we used to be.

Still, many people are lonely, it’s not great for happiness and health, and the advisory’s recommendations on how to reduce loneliness are good. But that doesn’t make it into an epidemic.

The issue might be that we’re mixing things. It does look like young adults are less happy than they used to be, but this might not be because they’re lonely. It might be something else. Social networks and phones are strong candidates to explain the issue. How specifically could they do this? Maybe FOMO, social comparison, bullying…

Why does this matter? Because if we don’t diagnose a problem properly, we can’t solve it. If we blame young adults’ misery on loneliness, we might push them to hang out more with the very people causing their distress.

My hypothesis is that the Internet naturally creates new interaction mechanisms between people, and we just haven’t learned how to handle them. The same way as speech, writing, the printing press, radio, or TVs created social upheaval, the Internet has as well. In this case, I fear that the Internet boosts some of these detrimental social mechanisms like bullying. Before, bullying would stop at your home’s doorstep and fade with memory. Now neither are true, and network effects can magnify the negative impact.

These won’t be solved by closing your phone and walking out to see your neighbor. If your neighbor is in the know, they might avoid you or, worse, demean you to prove their allegiance to the broader group.

If you find research on these topics, I’m interested.

Better Social Interactions

I’ve talked before about social rules to hack bonding. Connecting with people is hard, but so rewarding. Can we force the process?

This thread has some ideas:

It’s geared towards parties. Some examples:

Pomodoro party: every 25 minutes a bell sounds and people have to switch conversational groups.

Phenomenological potluck: everyone brings along one unusual sensation for others to try.

Knaves party: everyone picks a few topics to consistently lie about throughout the party.

Dinner with conversation menu: along with a food menu, there’s a conversation menu with topics to discuss.

Gameshow party (15 guests max): The party is split into three teams of five. Every guest brings an idea for a minigame that all teams compete in, as if they were in a gameshow. E.g, one-minute PowerPoint standup presentation (without prep), quizzes, who am i?, Mario Kart, etc. Losers take shots!

Brazil and the Amazon

As you might have read in a previous article, I am dabbling with YouTube. This was my first stab at sharing amazing facts about the Amazon:

PythonMaps made this beautiful map of the forest in Brazil:

Note how the Amazon Rainforest surrounds the river, and how the entire southwest does not have as much forest: it’s the Brazilian Shield, which concentrates most of the agricultural development in the country.

As we discussed in The Amazon Rainforest, the parts that are really in danger are the holes you can see in the bottom border of the forest area. These are the places with the most illegal forest clearing. Thankfully, forest clearing has dropped by 70% year-over-year under President Lula da Silva, who got elected at the end of last year.

As we discussed in the article, the Amazon Rainforest has very little population, as most of Brazil’s population is concentrated on the coast. This graph illustrates that point well:

As you see, it leaves a space between the forest and the coast, which is mostly the Shield. This area has been seeing a heavy investment for agriculture in the last few decades, and is growing more populous.

As we discussed in the article about Brazil, this coastal illustration might not be stark enough, as the population is not just concentrated along the coast. It’s concentrated specifically in some cities, which frequently behave akin to city-states.

AI is Killing Jobs

I’ve discussed earlier this quarter what jobs will disappear due to AI and when, and why we don’t see the impact of automation in statistics yet.

We’re experiencing this now.

Normally, when a new technology destroys jobs, it happens during a downturn. In economic boom times, companies are focused on hiring and expanding. In busts, they cut costs and focus on automating.

The recent explosion of AI is happening just as the tech world is going through a downturn, so both of these trends are combining and jobs are disappearing in tech.

IBM froze hiring and is considering replacing 7,800 jobs with AI. Left and right, we hear stories about people who lost their job to AI, or where AI took over all their most interesting tasks.

Now, a lot of this is anecdotal evidence. It might very well be that in aggregate, or in the short-medium term, more jobs are created than destroyed. But this is a stark illustration of exactly the type of concern we should have.

In my personal experience, seeing what’s happening around me, I have the feeling that big changes will come in fields like sales, marketing, design, and engineering. Many might lose their jobs, while the rockstars in these fields might very well make much more money.

For example, if an engineer can develop things ten times faster, you might just need a handful of engineers to build an entire system instead of a huge team: they might be enough to build the system, and keeping the team small reduces coordination issues that arise with dozens of engineers who might not be on the same page.

The Map Is the Territory

In Internet and Blockchain Will Kill Nation-States, I explained the concept of print capitalism, where the emergence of nation-states was caused by the printing press, which created modern languages and communities of ideas.

While doing research for the article Maps Distort How We See the World and Are Maps Deceitful?, I stumbled upon a complementary theory: that the printing press also gave birth to nation-states through its marriage with cartography.

Cartography exploded at the same time as the printing press, in the early 1500s, during the Age of Discovery. Explorers needed better maps, and they used the printing press to distribute them. This made people see the world through maps, and this had tremendous consequences for the world.

For example, maps depicted land as a homogenous geometric surface that could be measured, divided, and controlled by rulers. That also made rulers compare and compete with other states based on their territorial size and shape, creating a logic of expansion and consolidation. The paper argues that this transformation had profound implications for the nature and legitimacy of political authority, as well as for the emergence of nationalism and citizenship.

Borders got drawn on maps, which pushed rulers to enforce them more. They became fixed lines rather than flexible zones. They enabled rulers to claim exclusive sovereignty over their territories, creating a logic of exclusion and differentiation.

An example of this is the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, often seen as the origin of the modern state system and international law. After the terrible Thirty Years War in Europe, countries signed this treaty that fixed borders and claimed that each country should respect other countries’ borders and sovereignty. This is impossible without maps.

We can see the same thing in the Scramble for Africa, where Europeans decided to split the control of the continent based on its maps. In fact, this is a stark example of the map determining the territory, and not the other way around.

Every now and then, we must be reminded that the map is not the territory. There’s something special about appearing on a map. It makes it real. As a result, powers that control territory become much more powerful than they deserve to be. This gives them even more power. For example, think of a country like Somalia, which really isn’t a state—too weak for that. Global multinationals are probably more powerful. But since they don’t appear on maps, we don’t even think of comparing them.

So as maps gave power to territorial entities, they took it away from non-territorial ones. The most obvious one is the Christian Church. Another one might be feudal entities: because you can’t show every political level on a map, map-makers tended to show the highest level. This took power away from lower nobles.

More Ocean Currents Subverted

In Why Are Tropical Waters Dead, and Can They Kill Europe?, I explained how ocean circulation works.

I also explained why global warming might jeopardize this. Ice used to cool the hot, salty water from the Gulf Stream; but now it also dilutes it, because frozen freshwater is melting and mixing with the saltwater, preventing it from plunging

A new paper in Nature is suggesting that the same thing is happening in the Antarctic Ocean.

The Economist on Masks

In Do Masks Work?, I explained why a very deep meta-analysis on the performance of masks might be wrong in concluding that they don’t work well. A month and a half later, The Economist ran basically the same story, highlighting exactly the same papers, in a similar way.

I’m glad to see you’re more readily receiving deeper information via this newsletter than from The Economist!

Earthly Winds

I’ve told you a few times about trade winds, westerlies, and the like. But these winds are hard to visualize. Fortunately, Jupiter is doing us a favor by being a gas planet and showing us what these currents look like. For the video, go to the source tweet: