A Trip Around the World of Heat, Mountains, and Poverty

After I shared my novel theory of why warm countries are poorer, your avalanche of amazing comments prompted me to respond with two articles. But I kept thinking about some of them, especially this theme, summarized in Astral Codex Ten:

I find this very interesting, and far more thoughtful than most attempts at this question, but I’m pretty concerned about his answer here to the objection that India, Cambodia, etc birthed great empires while being hot and non-mountainous. He says that they may have had high GDP, but always had low GDP per capita, which he pinpoints as the real measure of wealth. My impression is that pre-Industrial Revolution, all countries had low GDP per capita, because they were in a Malthusian regime where economic improvement translated to population density rather than increasing per capita GDP. Any differences between regions reflected minor fluctuations in the exact parameters of their Malthusianism and were not of any broader significance. So I think the India etc objection still stands and is pretty strong.

In other words: In the past, wealth always became people, because humans would simply convert their money into food to feed more children, up until they couldn’t afford to feed any more people.

I respect the author, Scott Alexander, tremendously, so that gave me pause, and I’ve been pondering this ever since.

Eventually, I concluded that we could explore this question together on a trip around the world: Fly over a multitude of countries, zoom in on their most characteristic features of development, and from what we see, draw some rules of development and explore how heat and mountains might have affected them.

I’ve been wanting to do this forever anyway, and Christmas week is the perfect time, so please take your seat, fasten your seatbelt, pull up the window shade, and get ready for an adventure!

The World Under Malthus

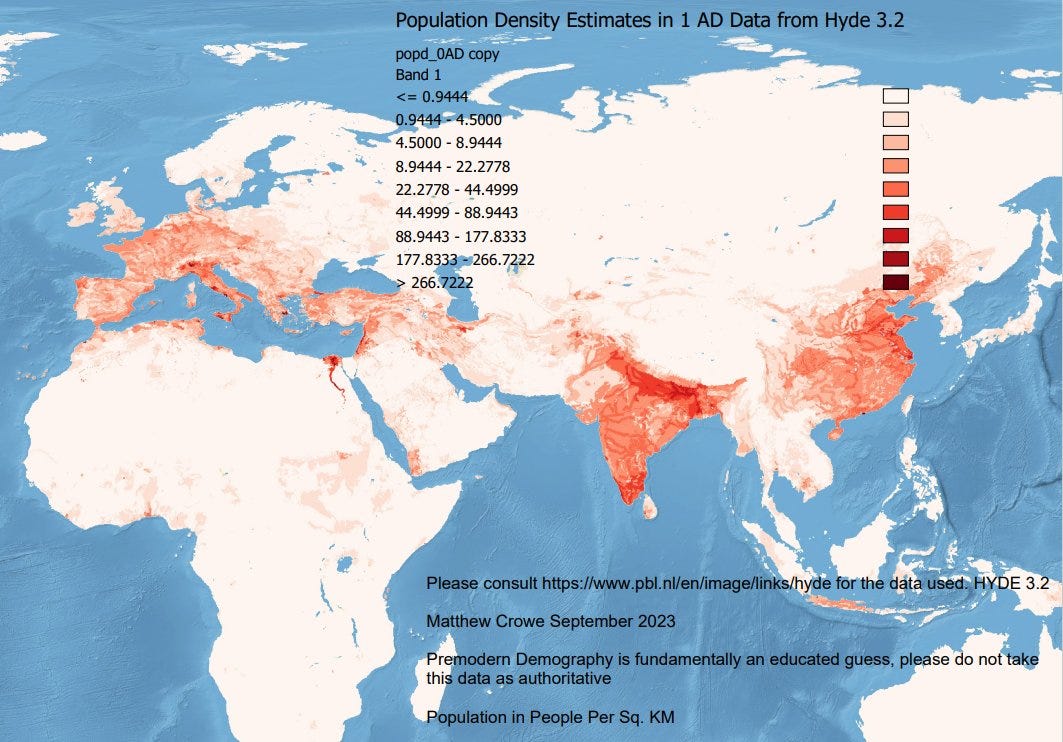

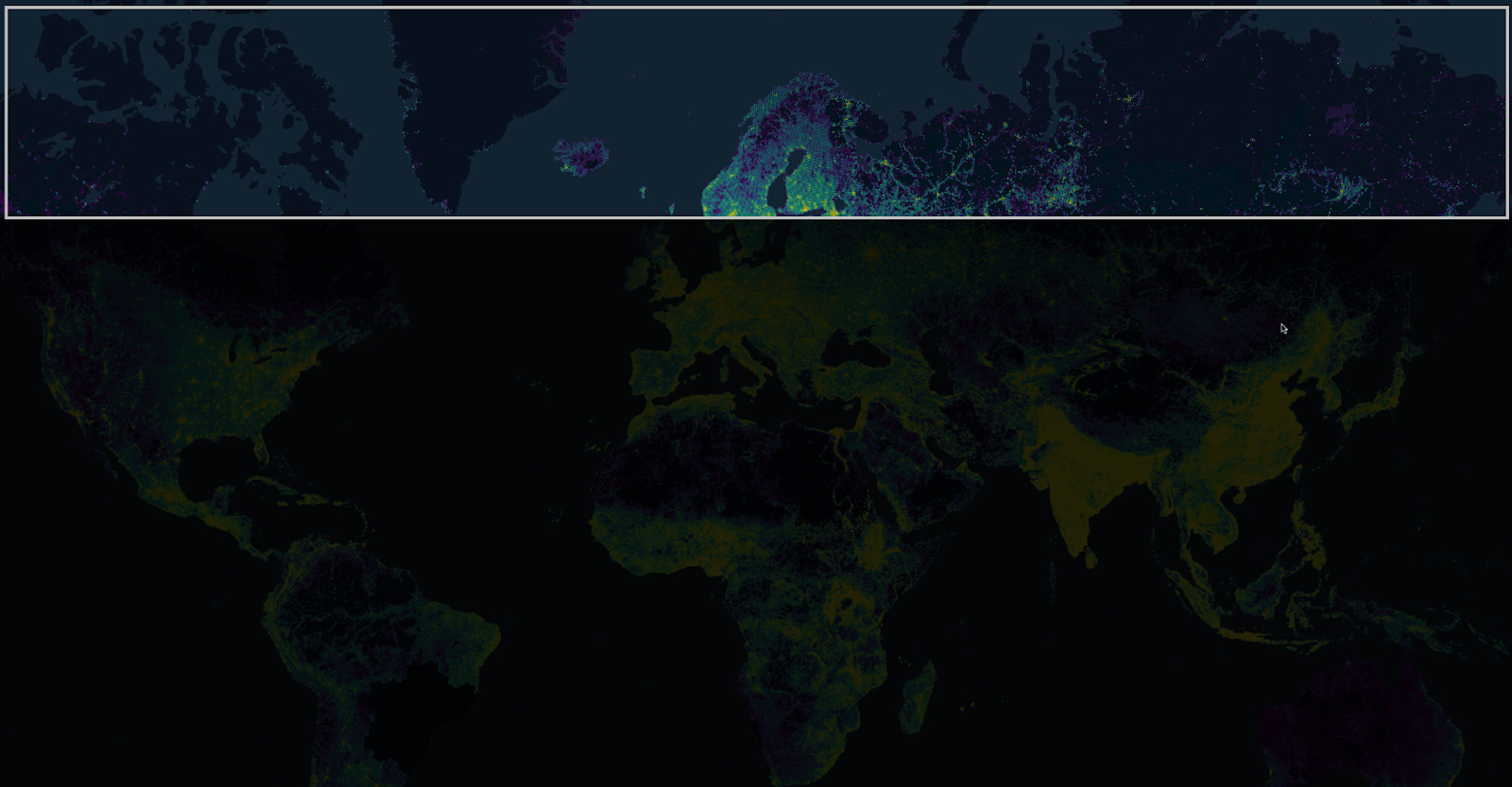

I have a very hard time finding maps of world population density before 1800. Here’s one from 1 AD:

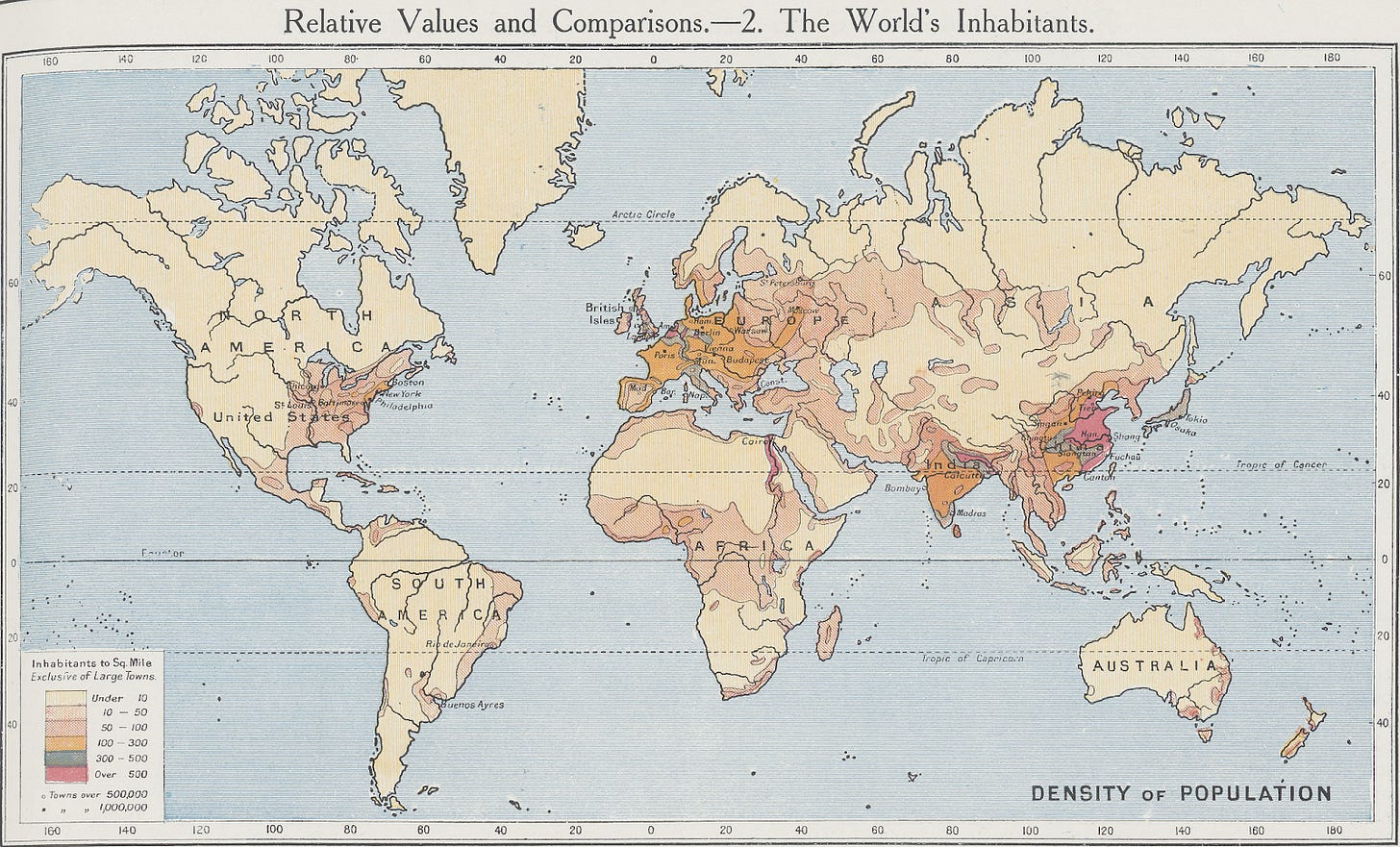

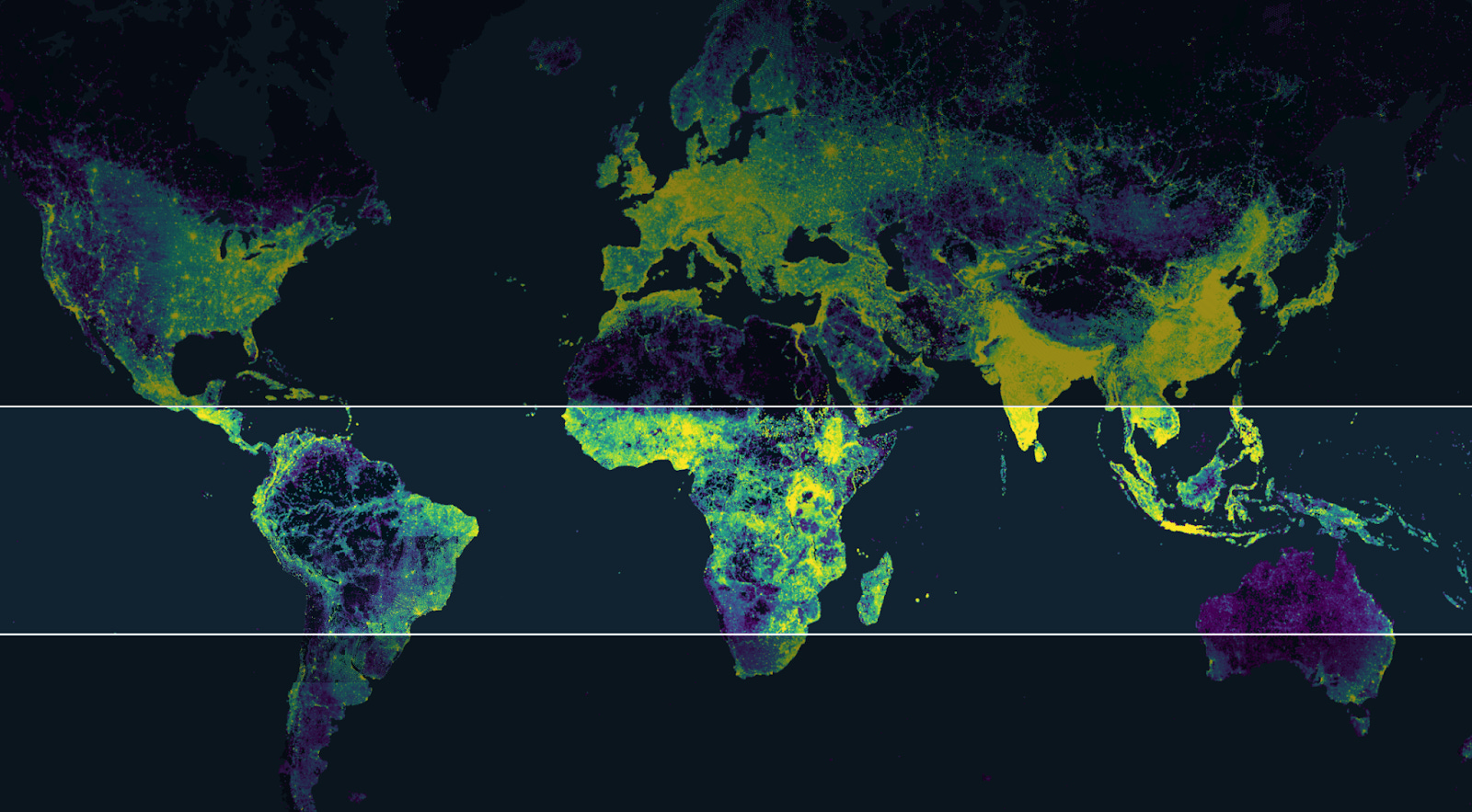

Which reminds me a lot to this map:

And this population density map for 1908:

Put together, we can conclude that the places that had any substantial native population before the Industrial Revolution were:

Europe, and more recently its temperate offshoots (Eastern US, Australia / New Zealand, Buenos Aires, South Africa)

The Middle East (Turkey, Mesopotamia, and the Levant)

India

China

Japan

Egypt

What patterns can we notice?

Most of these are outside the tropics.

There is, indeed, a dearth of population around the equator.

The biggest outlier is India, especially southern India, which is densely populated yet close to the equator.

There are some other pockets of population: the island of Java in Indonesia, Nigeria, western Yemen, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Nigeria, Mesoamerica, or Northern Colombia and Venezuela.

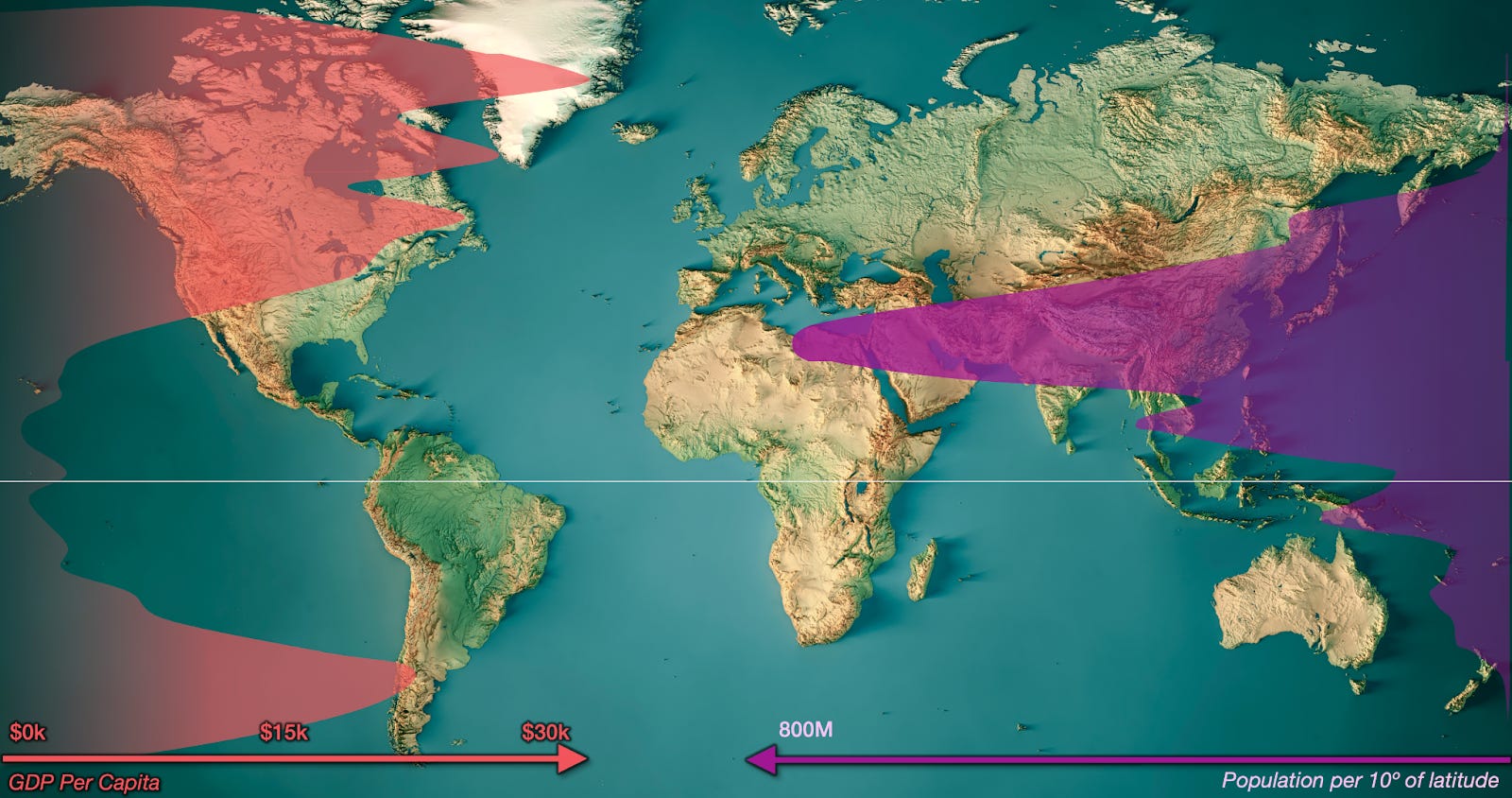

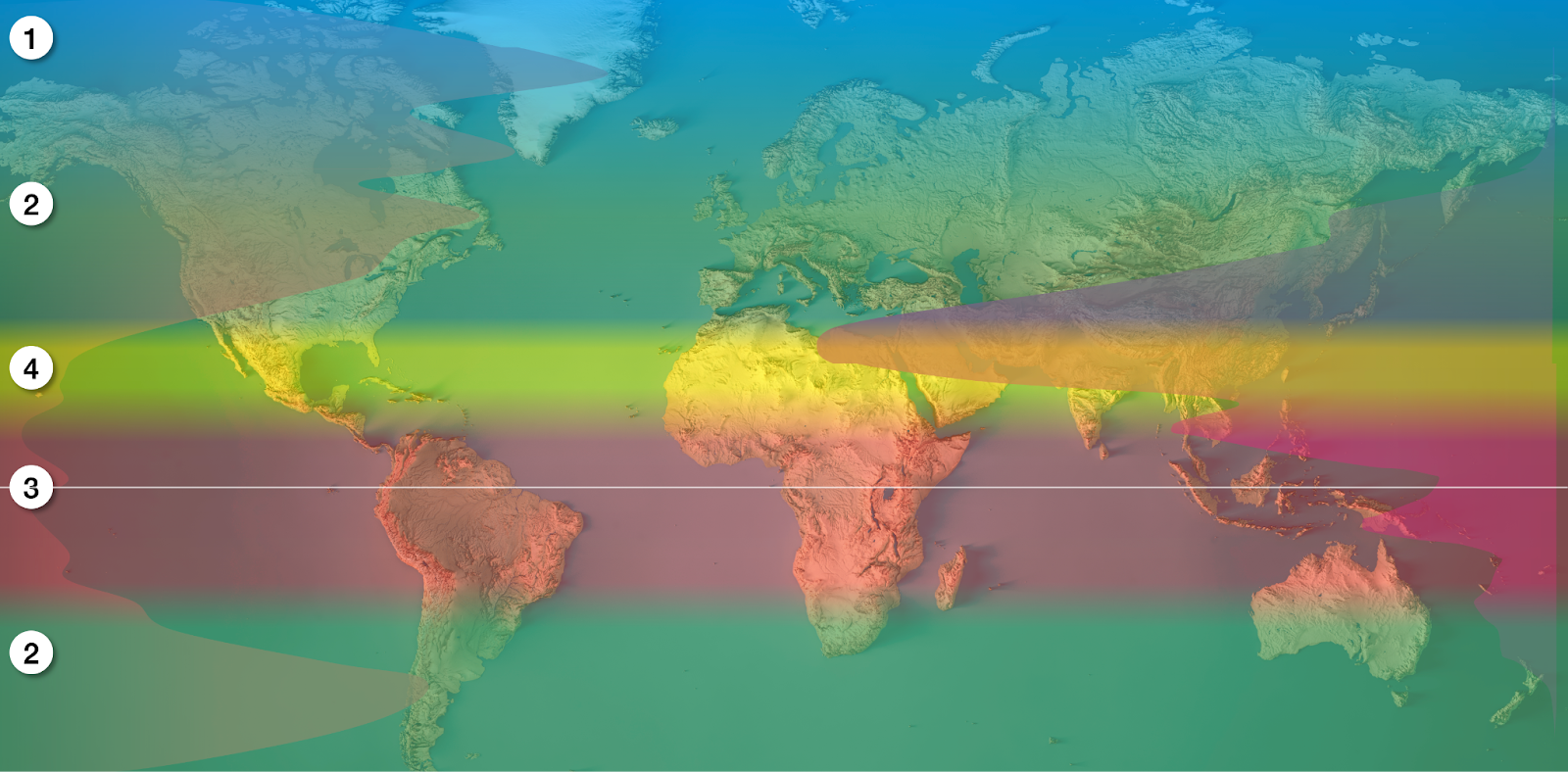

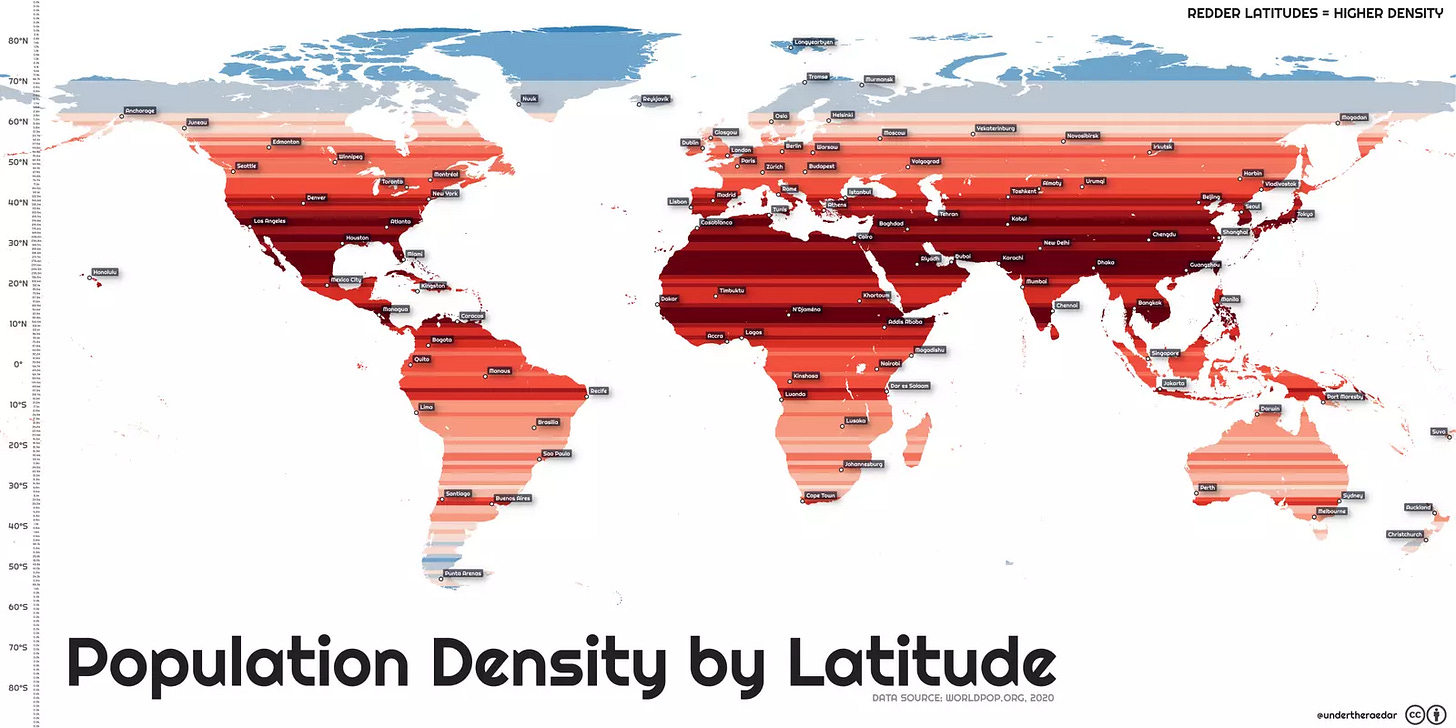

Let’s compare this to a map of population and GDP per capita per latitude today:

We can basically see four main regions:

The very cold and rich region in the Northern Hemisphere, in blue

The rich temperate regions in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, in green

The poor equatorial region, which is also not very densely populated

The transition region, which is poor but very densely populated

Regions 1 through 3 fit the theory that cool countries are richer pretty well. The key question is around region 4: If it is poor today on a GDP per capita basis, why are there so many people? Why has it hosted big empires throughout history?

I don’t think we need to rehash why region (2) is good, so our trip will take us quickly to the polar region (1) first. Then, we’ll switch out the heater for the AC to travel to the equatorial region (3). Finally, we’re going to the more contentious tropics (4).

Polar Regions

If you look at a map of population density, you’ll realize this wealth just describes Europe’s Nordic countries.1 It’s nearly all Finns, plus some Swedes, Norwegians, and a handful of Icelanders and Russians.

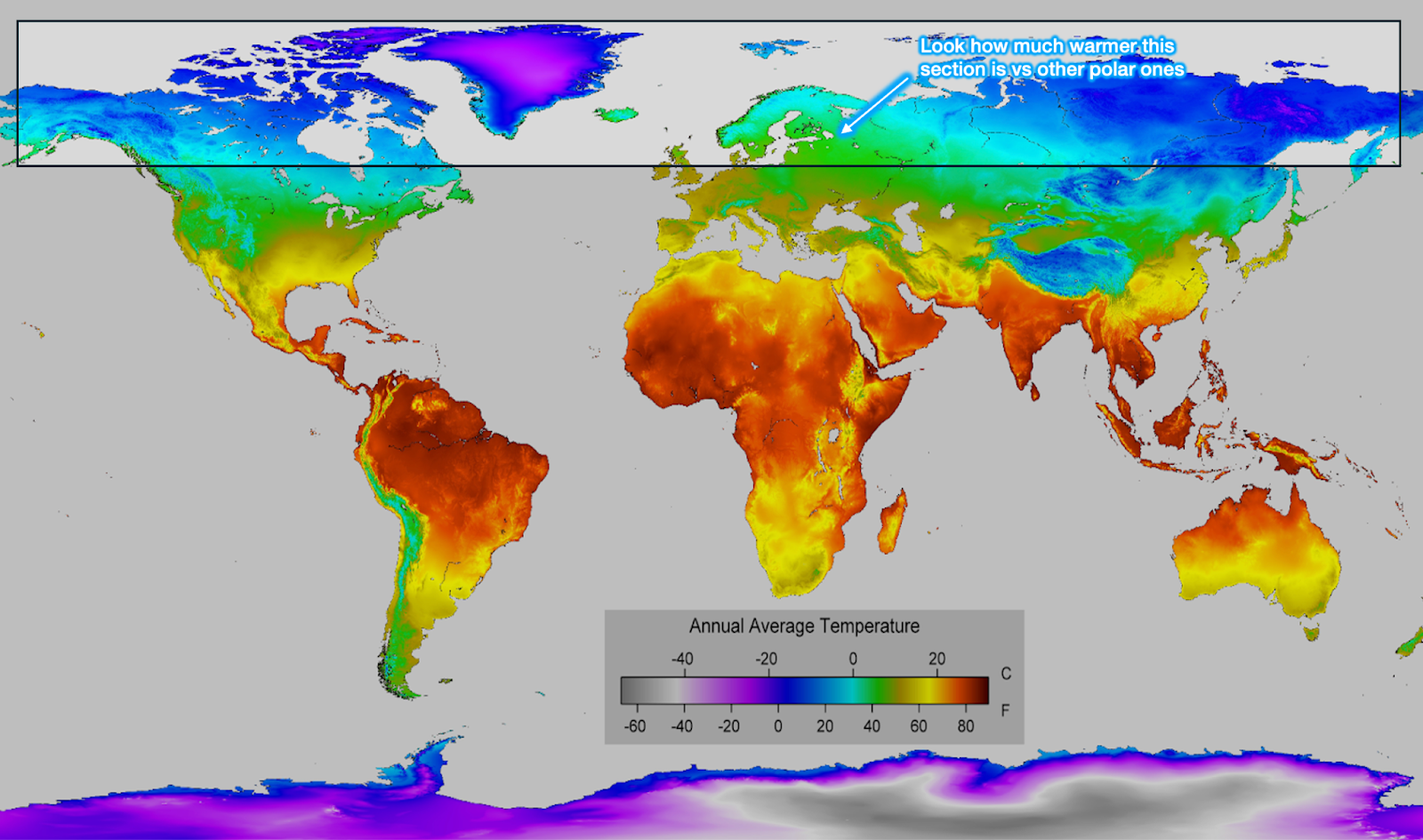

Their development patterns are quite similar to those of slightly more temperate regions, because they have a similar climate:

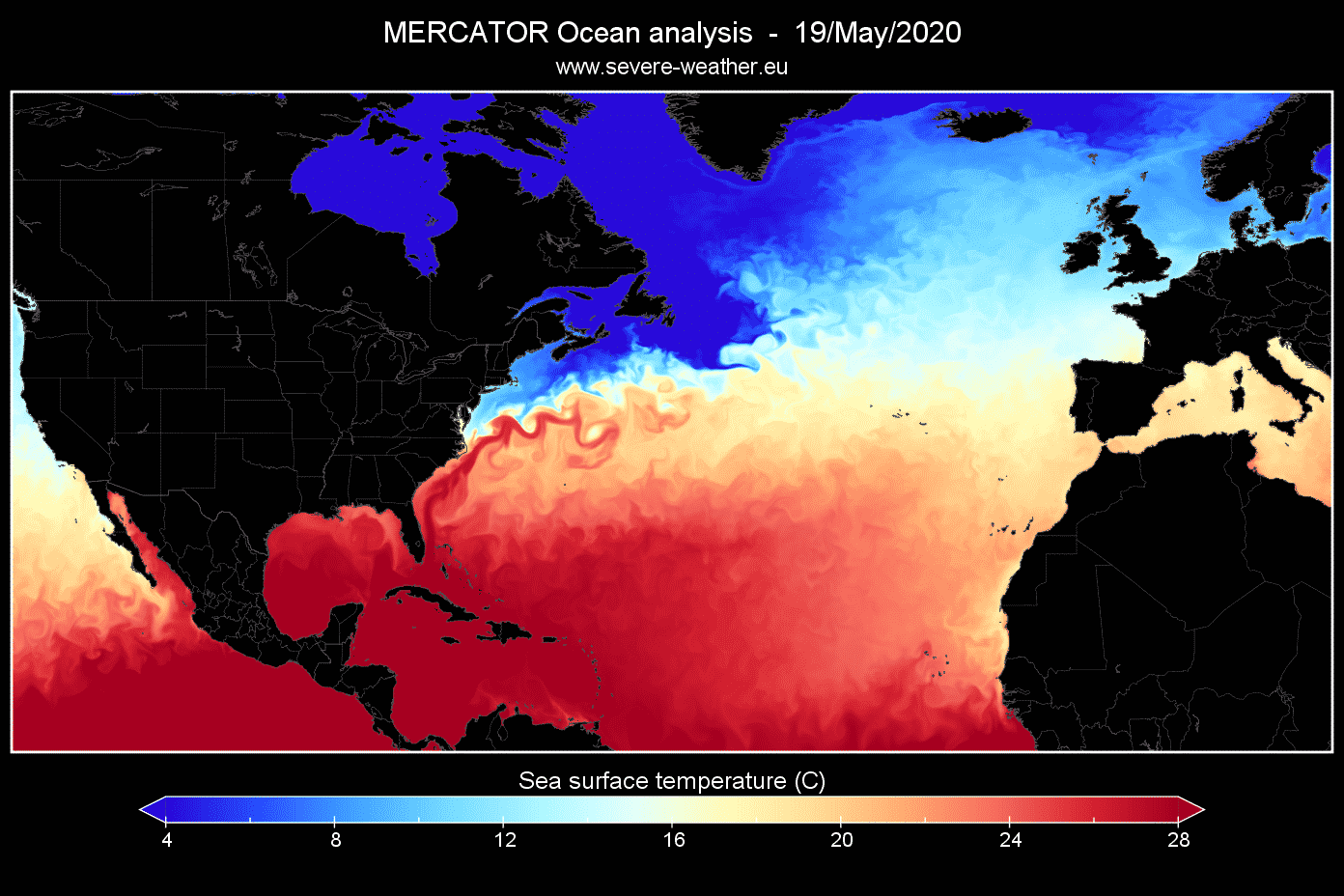

They’re just farther north in Europe because the Gulf Stream (and the AMOC) warms them up.

OK so (1) is basically like (2), the temperate regions, extended upwards by the unique shape of Europe and the rotation of the Earth. This also explains the southeastern diagonal of temperatures and populations we saw before: Europe is warm despite being farther north because of the Gulf Stream.

Now let’s travel to the equatorial region, and here is where it starts getting interesting.

You can see it’s quite poor and not very populated.

You might assume that it’s less populated simply because it has less landmass, not because its population density is lower, but this map displaying population density per latitude shows basically the same thing:

If we look again at a population density map today:

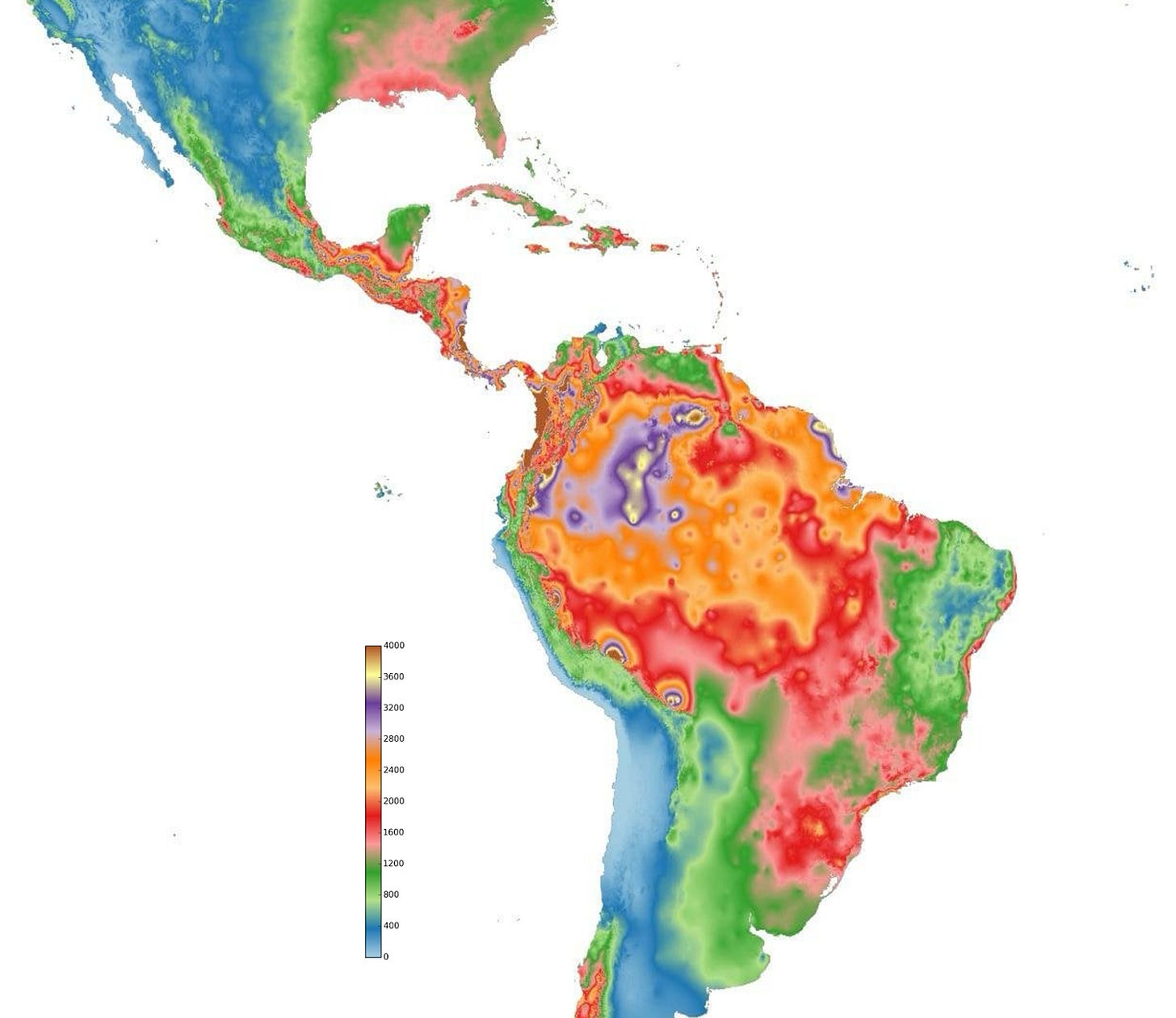

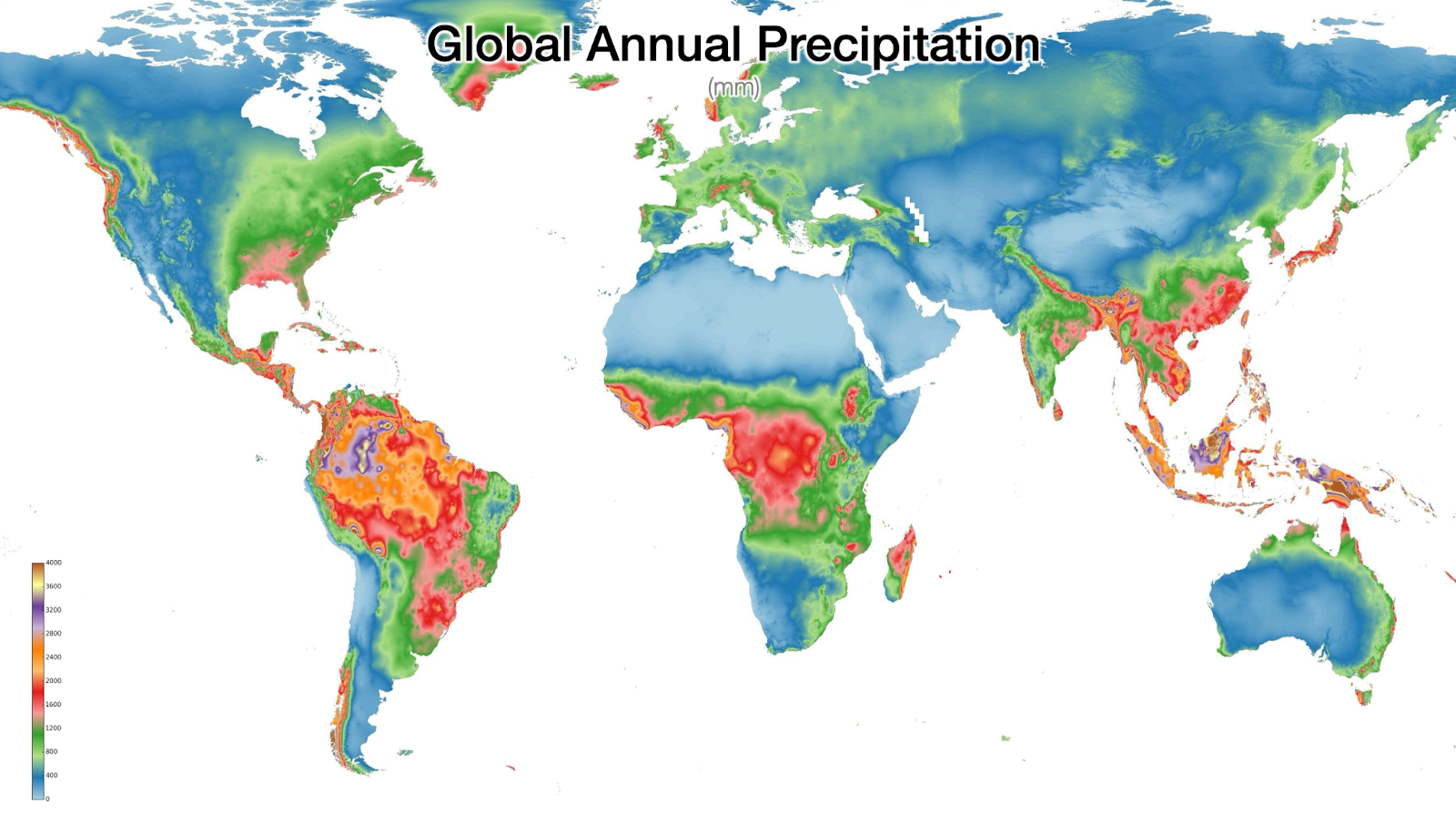

The only part here that also seemed to have a big population centuries ago is India. We will look at it later on. Right now, we should wonder the opposite: Why are there so many very empty areas here? Here is a map of global annual precipitation:

Note how rainfall is brutal in Latin America (LatAm) between southern Mexico and Brazil, in Africa (from Guinea Bissau in the west to the Congo in the center), and Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia and Malaysia). Now let’s compare that to a map of erosion caused by rainfall:

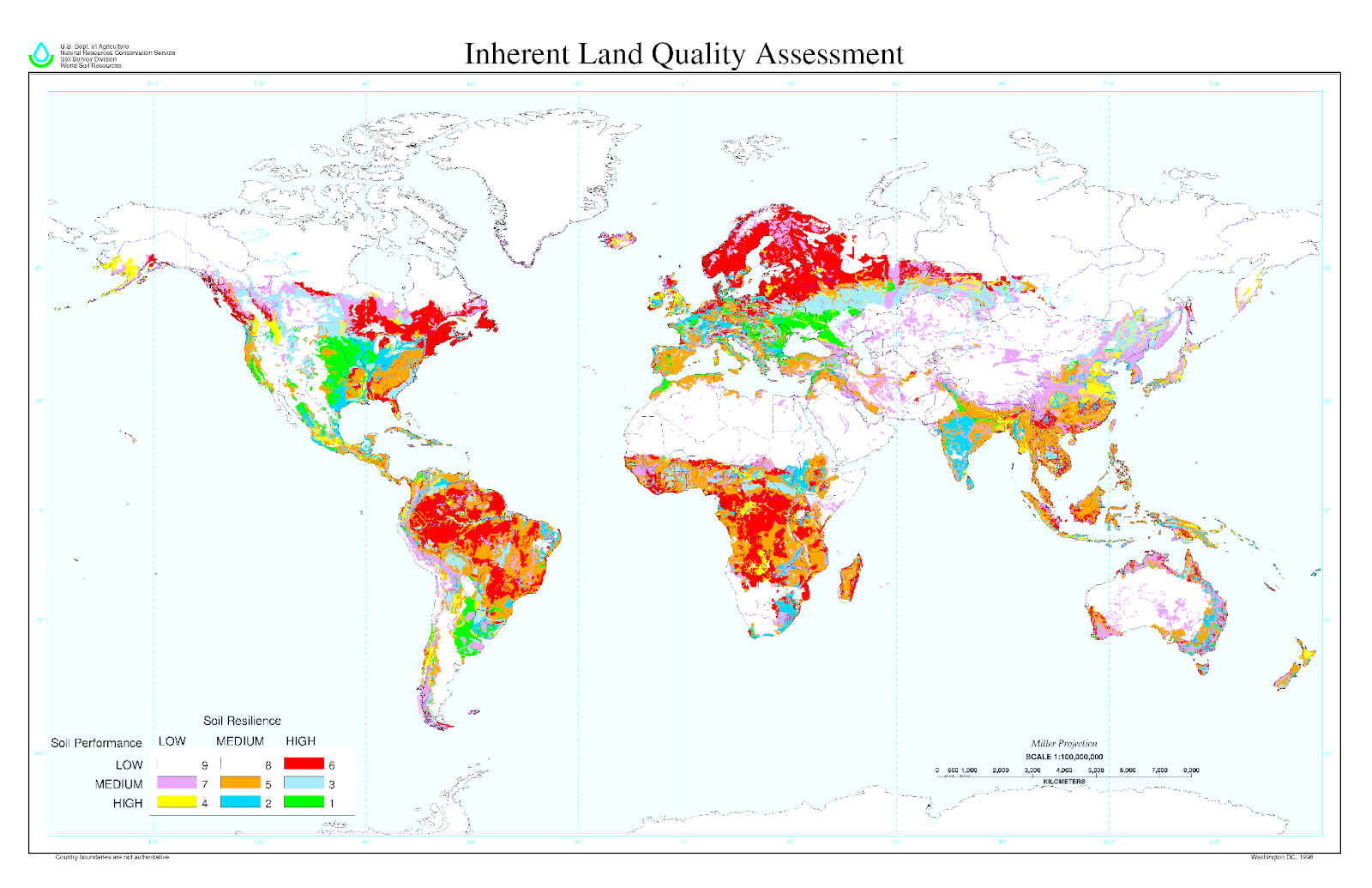

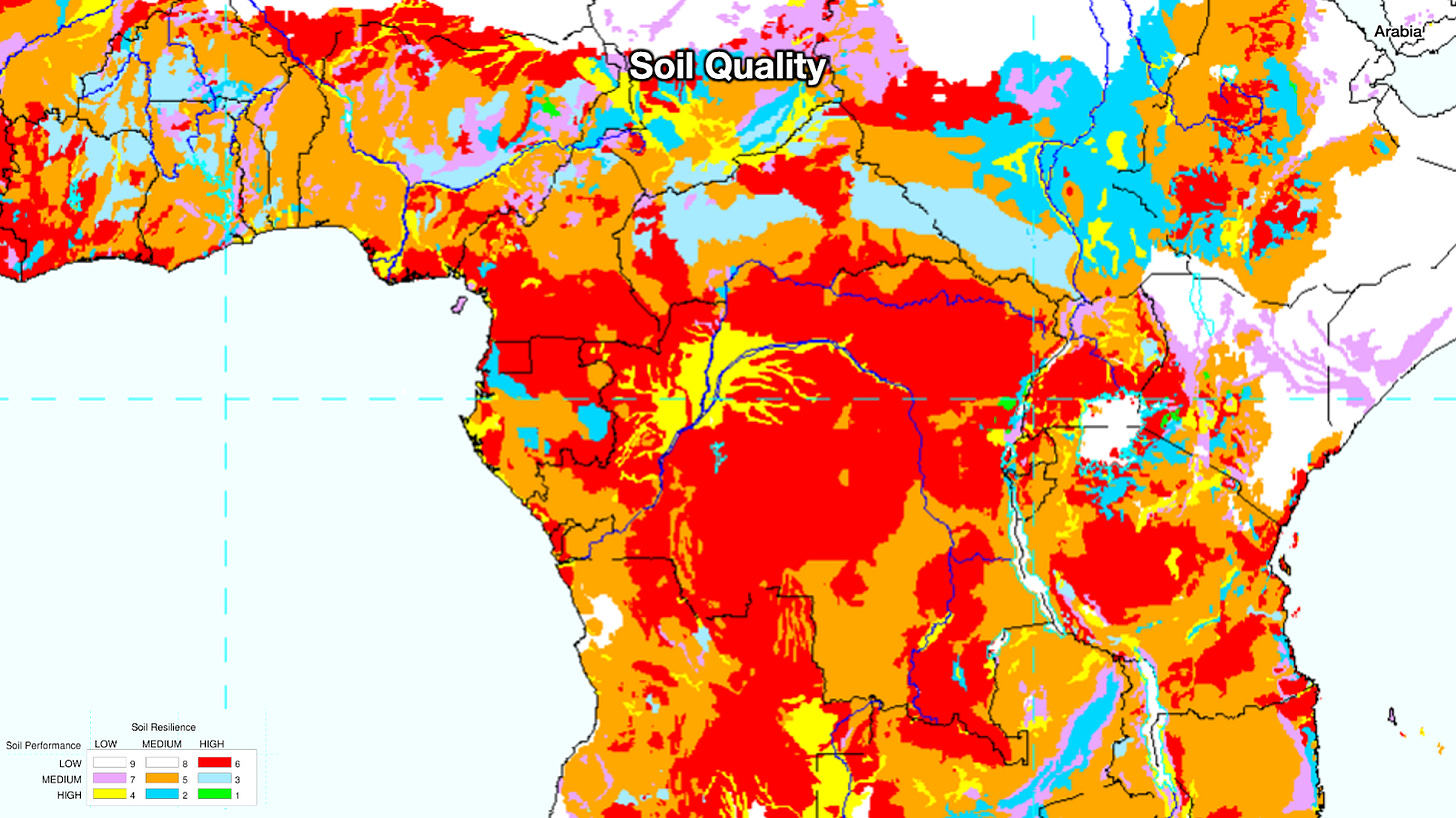

Basically the same places that have lots of rainfall also have terrible erosion from rains. And this is a map of land quality:

Virtually all the regions hit by lots of continuous rains have crappy land. Let’s take a few examples, starting with America, because the continent is the only one elongated across all latitudes, so it clearly gives a sense of what happens at each one.

The Americas

Let’s zoom in on that precipitation map.

Brazil

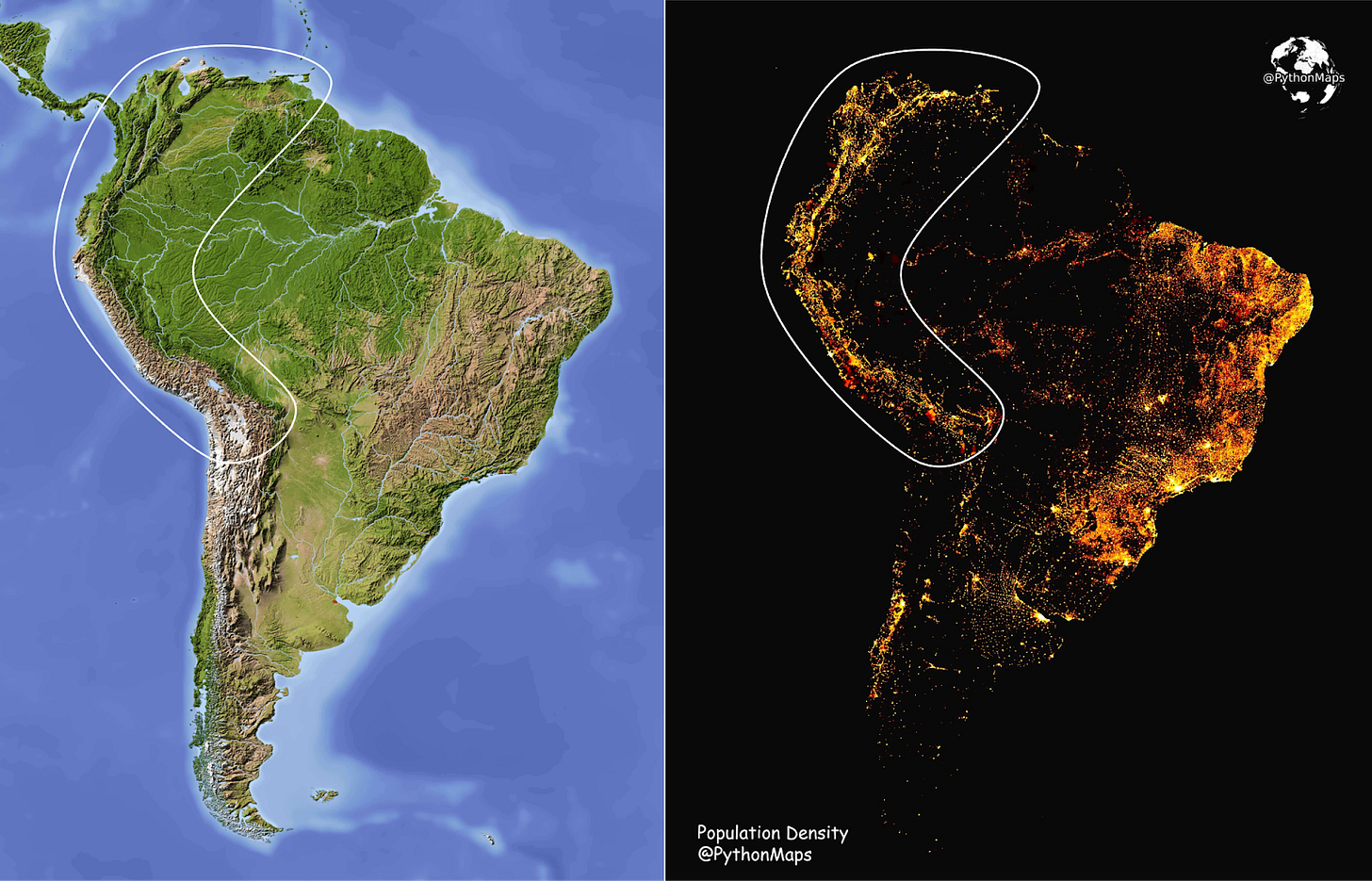

When we looked at Brazil, I shared the country’s topography and population density:

Most people live on the mountainous coasts. São Paulo is 760 m high, for example. The south (cooler) is more populous than the north. And most of the cropland is actually to the south, as far from the equator as possible (and in the mountains!):

And more importantly and tellingly, the Amazon is completely empty. Yet it’s a massive flatland irrigated by a river system that competes with the Mississippi’s in terms of volume and number of big tributaries. Equivalent rivers in temperate regions (the Nile, the Ganges, the Yellow River, the Yangtze, the Mississippi, the Paraná…) are all densely populated.

If the Amazon had been in a temperate region, it would be massively populated and rich like them. But it’s empty, and not because of environmental protection efforts. It’s because its land is absolutely terrible for agriculture. When you hear that people are destroying the Amazon Rainforest, that’s not really true. The heartland is protected by geography. It’s the edges that are being destroyed. The Amazon is barren for agriculture because of the constant rainfall erosion.

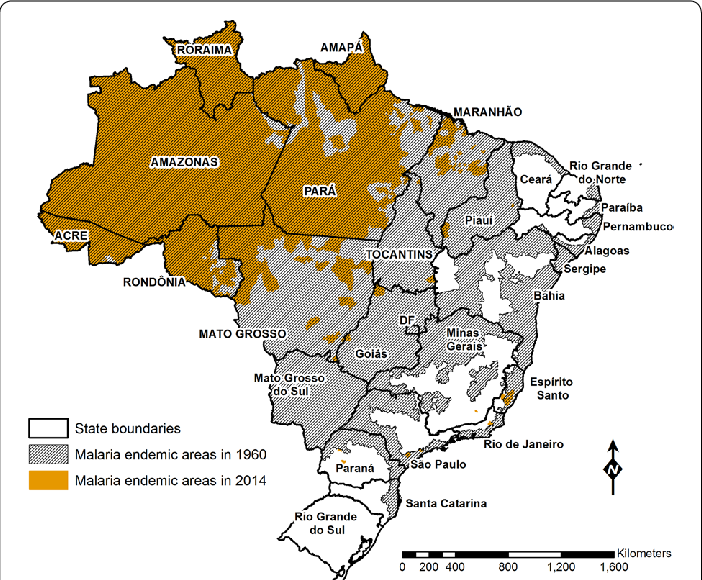

It’s not the only issue. Diseases, of course. But we can’t just take a map of current disease, because there are so many confounders. For example, more populous areas will have more sick people by definition, even if the population is healthier. They will tend to have more infectious diseases simply because there is more density. More advanced societies tend to have their particular diseases. What we want to get at, though, is what diseases prevented development in the first place. For that, I think we should take as proxies the diseases that are known to have caused the most trouble to humans throughout their development, and at the top of the list is malaria.

It’s especially active in the Amazon rainforest. Flat, low-lying, and rainy.

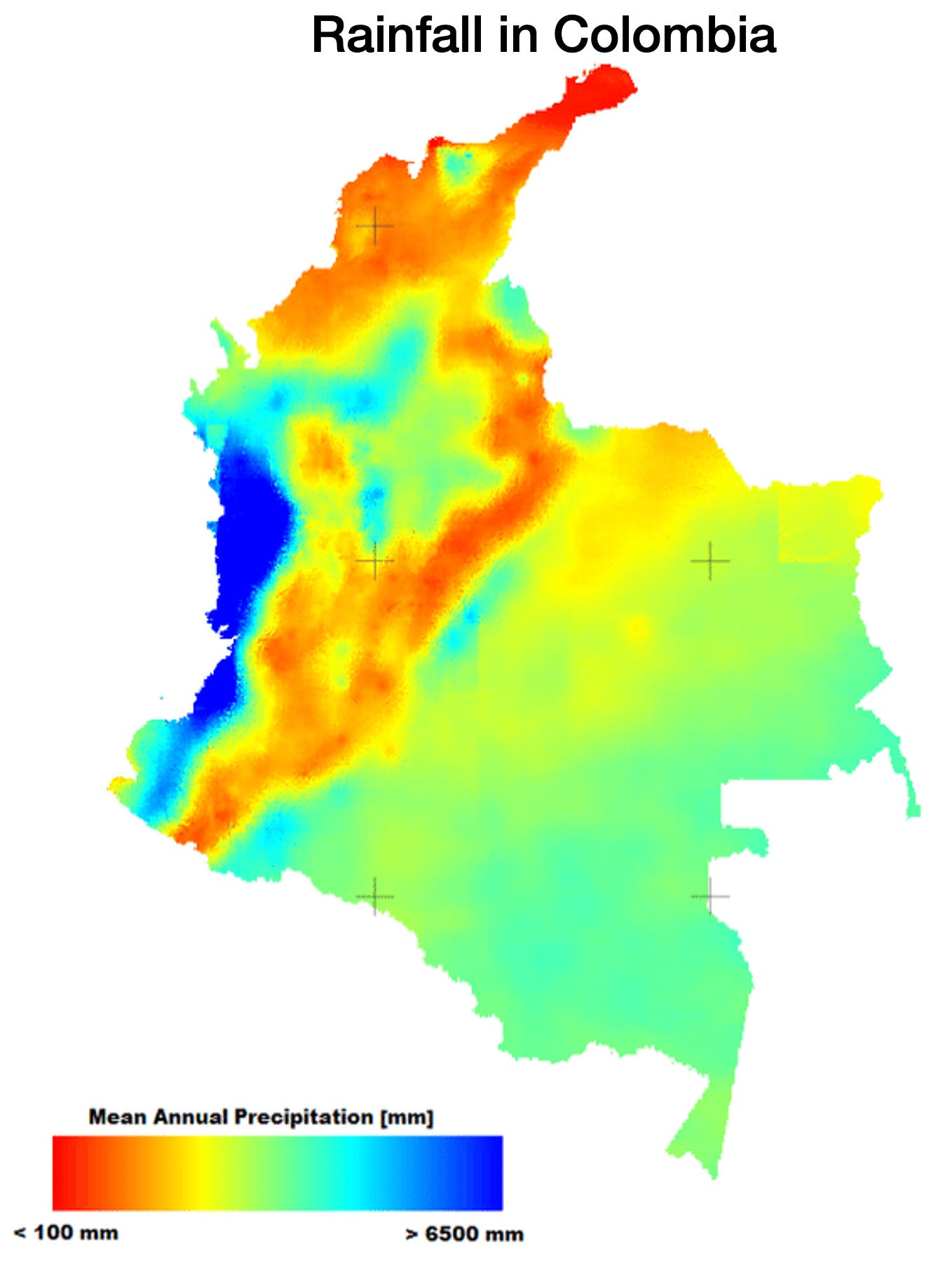

Colombia

To escape this terrible fate, Colombians live in the mountains, as we have seen.

Here’s Medellín:

In contrast, the Pacific coast is completely uninhabited, because it’s the hottest, rainiest part of the country, full of impenetrable jungle and hard to turn into cropland. Then, if you look around on the Internet, you’ll hear some of the themes we’ve discussed:

People from there are called lazy

Rife with disease

Very little infrastructure

The infrastructure that does exist gets destroyed frequently by the weather

Here’s a map of ethnicities in Colombia:

Basically the mountains in the middle are mostly mestizo or white, while the rainy, low-lying regions of west coast and the Amazon are Afro-colombian and indigenous respectively.

Meanwhile, the northwestern coast is actually somewhat populated. How come?

It doesn’t rain as much!

So we’re anecdotally seeing four factors directly affecting warm countries’ development in action

Rainfall: Extremely high around the equator, making farming nearly impossible, and hence big populations.

Disease: They affect the warm, humid, low-lying areas the most.

Mountains: People living higher up avoid so much rain and heat.

Sometimes, even close to the equator, some areas might not have as much rain, and the population is higher there than where it rains a lot.

Race: White people are especially prone to disease, so in these latitudes they tend to live in mountains. As we saw in the previous article, White presence is a market of development, even if we don’t know the causality (it can simply represent a higher transfer of human capital from the more developed Europe back then).

Now if we move east to Venezuela, it’s at the same latitude so we should see the same process. Do we?

Venezuela

This is a map of topography vs population density:

As you can see, most of the population is in the mountains. Caracas is at 900-1400 m of elevation.

Andes

Moving south, the same Colombian pattern of population can be found across the Andes, in Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia:

As we discussed, this is where we find the only equatorial civilization that emerged independently in the world, the Incas.

As we move south and we enter temperate regions, the pattern reverses, and the populations appear on the lower plains of Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile.

Panama

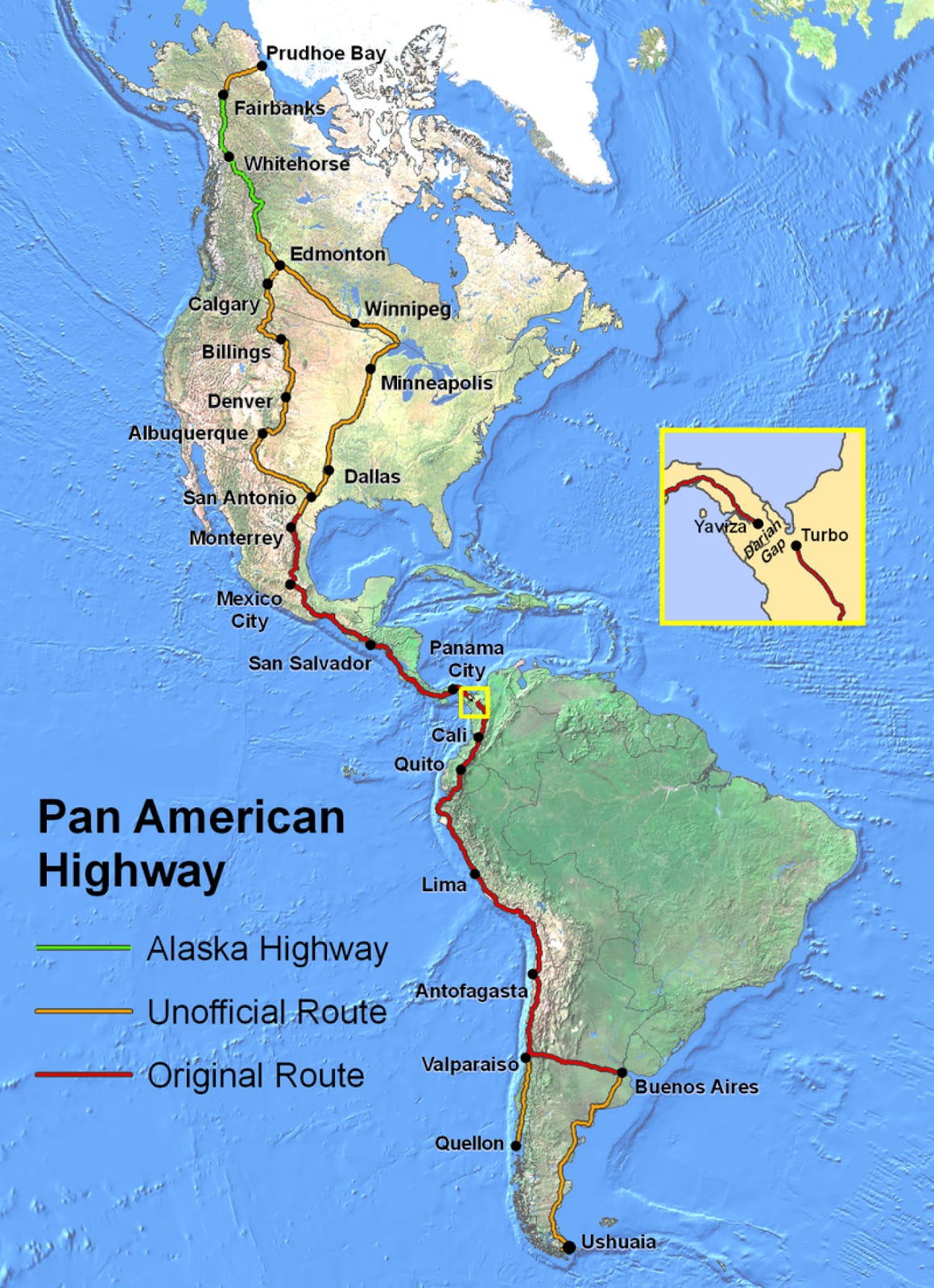

If we move north from Colombia, towards Panama, we find the Darién Gap, a region so brutally rainy that there is still no road that connects these countries! The Pan American Highway, which reaches both polar seas and traverses virtually all climates across dozens of countries, can not close this 100 mile (160 km) gap.

This is a zoom in on the area:

And this is what the Darién Gap looks like on the ground:

You can see many of the things we’ve discussed here. The quantity of water is hostile. It creates rivers, it creates mud, it erodes the soil (hence the mud. Look at the exposed tree roots), the humidity brings disease…

This is where the Panama Canal was meant to be built, but the disease burden prevented it from happening. It was pushed north, but the construction still cost tens of thousands of lives from disease. This is Wikipedia on the French attempt to build the canal:

From the beginning, the French canal project faced difficulties. Although the Panama Canal needed to be only 40 percent as long as the Suez Canal, it was much more of an engineering challenge because of the combination of tropical rain forests, debilitating climate, the need for canal locks, and the lack of any ancient route to follow. Beginning with Armand Reclus in 1882, a series of principal engineers resigned in discouragement. The workers were unprepared for the conditions of the rainy season, during which the Chagres River, where the canal started, became a raging torrent, rising up to 10 m (33 ft). Workers had to continually widen the main cut through the mountain at Culebra and reduce the angles of the slopes to minimize landslides into the canal. The dense jungle was alive with venomous snakes, insects, and spiders, but the worst challenges were yellow fever, malaria, and other tropical diseases, which killed thousands of workers; by 1884, the death rate was over 200 per month. The French effort went bankrupt in 1889 after reportedly spending US$287,000,000 ($10 billion in 2024); an estimated 22,000 men died from disease and accidents, and the savings of 800,000 investors were lost.

Central America

As you move north across Central America, the pattern continues.

Across every country, the population gathers on the mountains, seldom on the plains.

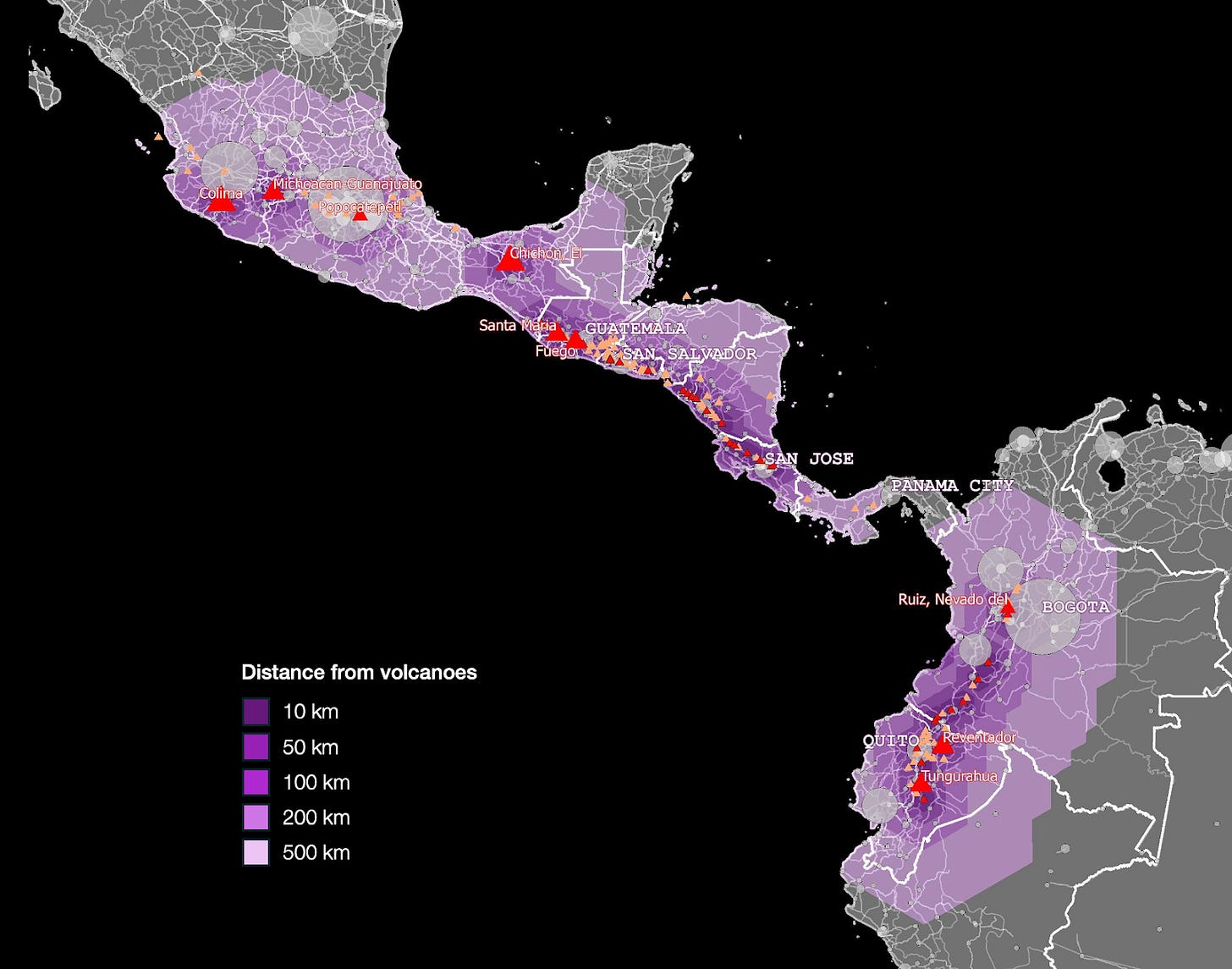

Many of these mountains, by the way, are volcanoes.

We saw exactly the same thing in Mexico.

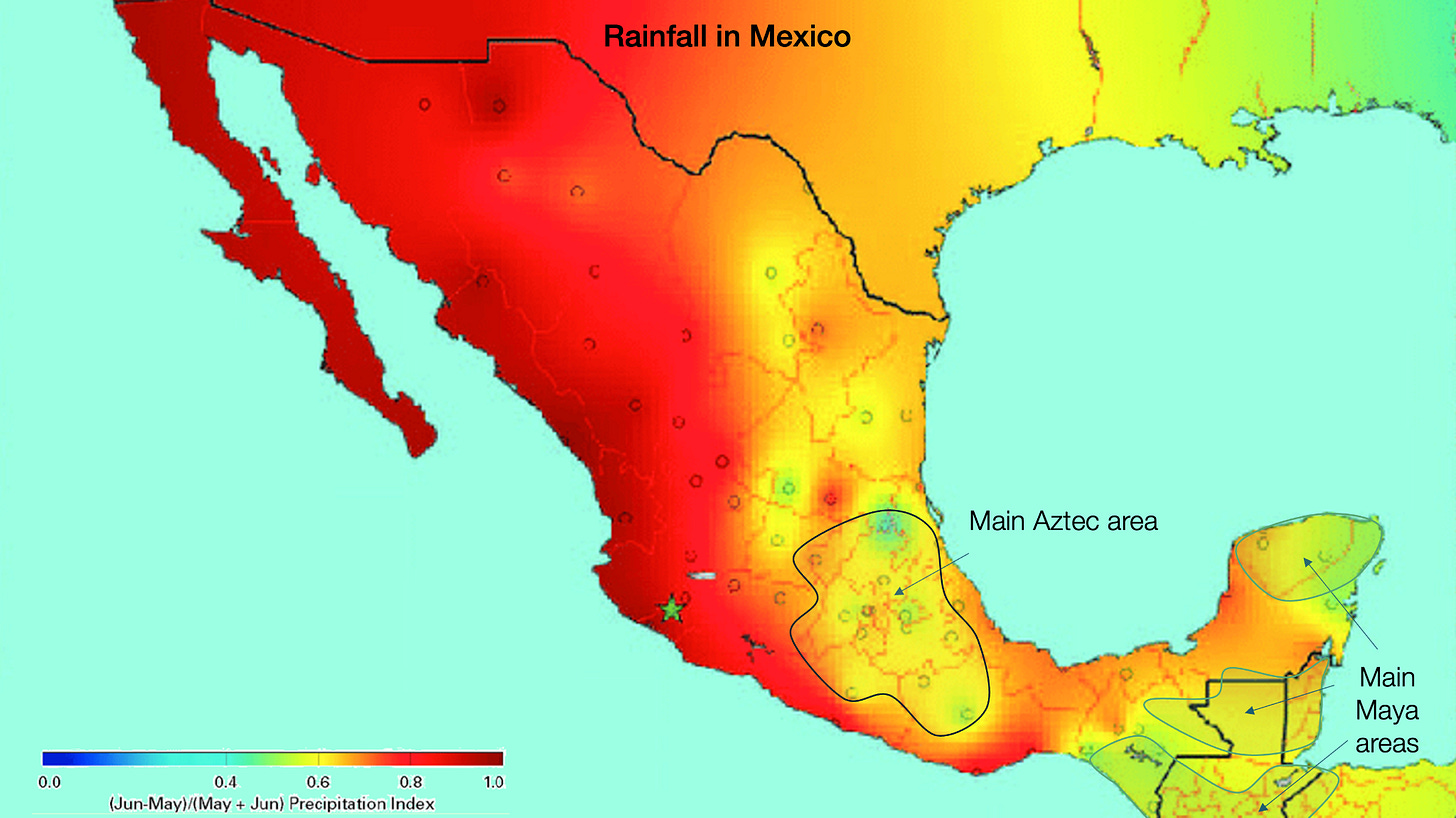

So, the two big empires to come from Latin America, the Incas and the Aztecs, were born in the mountains.2 Interestingly, in this entire area, the only other civilization to emerge was the Maya. Crucially:

The Maya lived in the driest parts of the region, as you can see on the map below

A sizable share of their settlements were on the mountains.

They were never a huge, centralized civilization.

They fell several times—maybe due to big rains and diseases?

If we look at a map of malaria prevalence in the region today, it won’t be a perfect reflection of historic conditions, because lots of work has been done to eradicate it, but here’s what we have:

It’s consistently prevalent on the biggest plains close to the equator.

Now look at this map, showing the risk of landslides in Central America:

This adds one more factor to our framework: Mountain societies also have to deal with landslides as an obstacle to development.

So that’s it for America. Let’s move on to Africa.

Africa

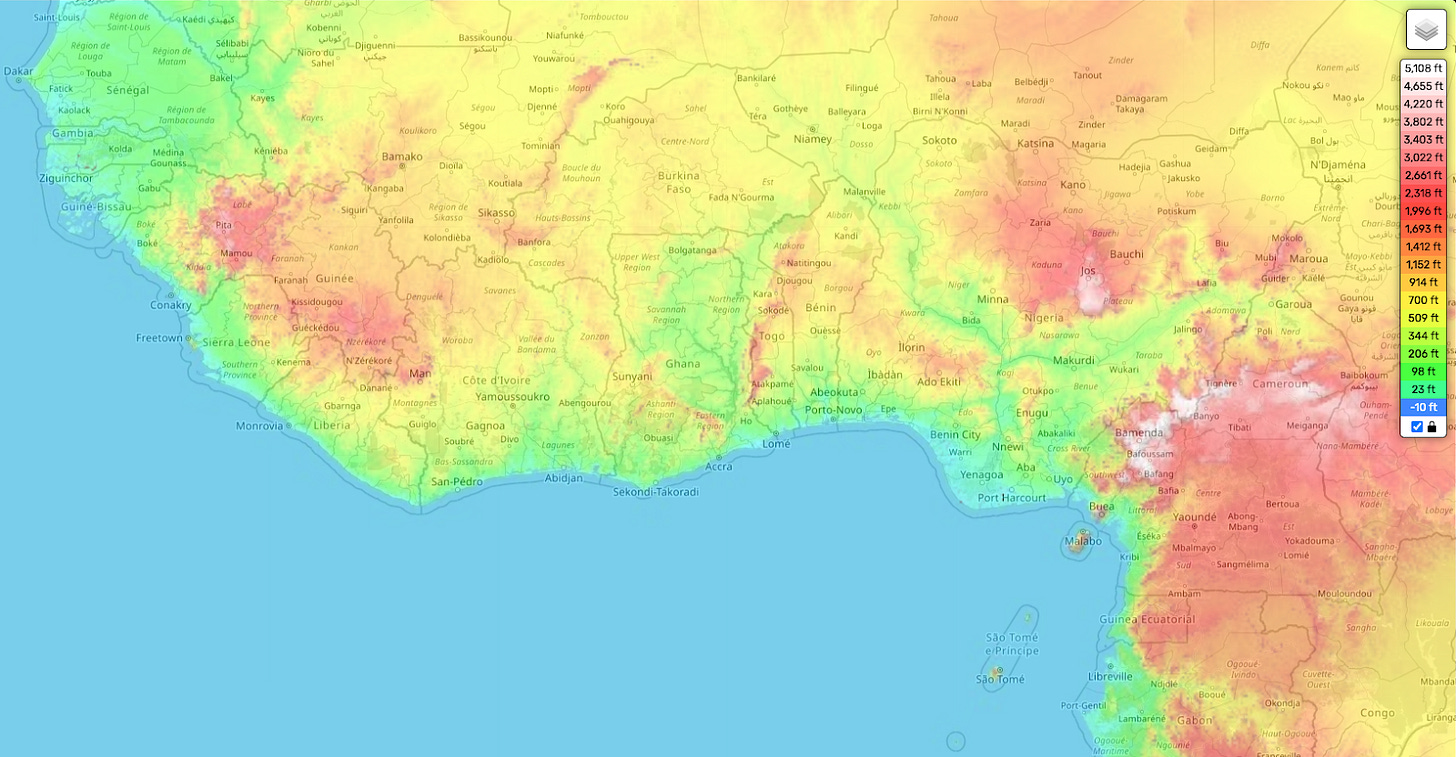

Let’s compare rainfall with topography and population:

There’s a ton going on here, so let’s break it down. We’re going to move quickly through the areas we visited in the original article and dive deeper into the more interesting ones.

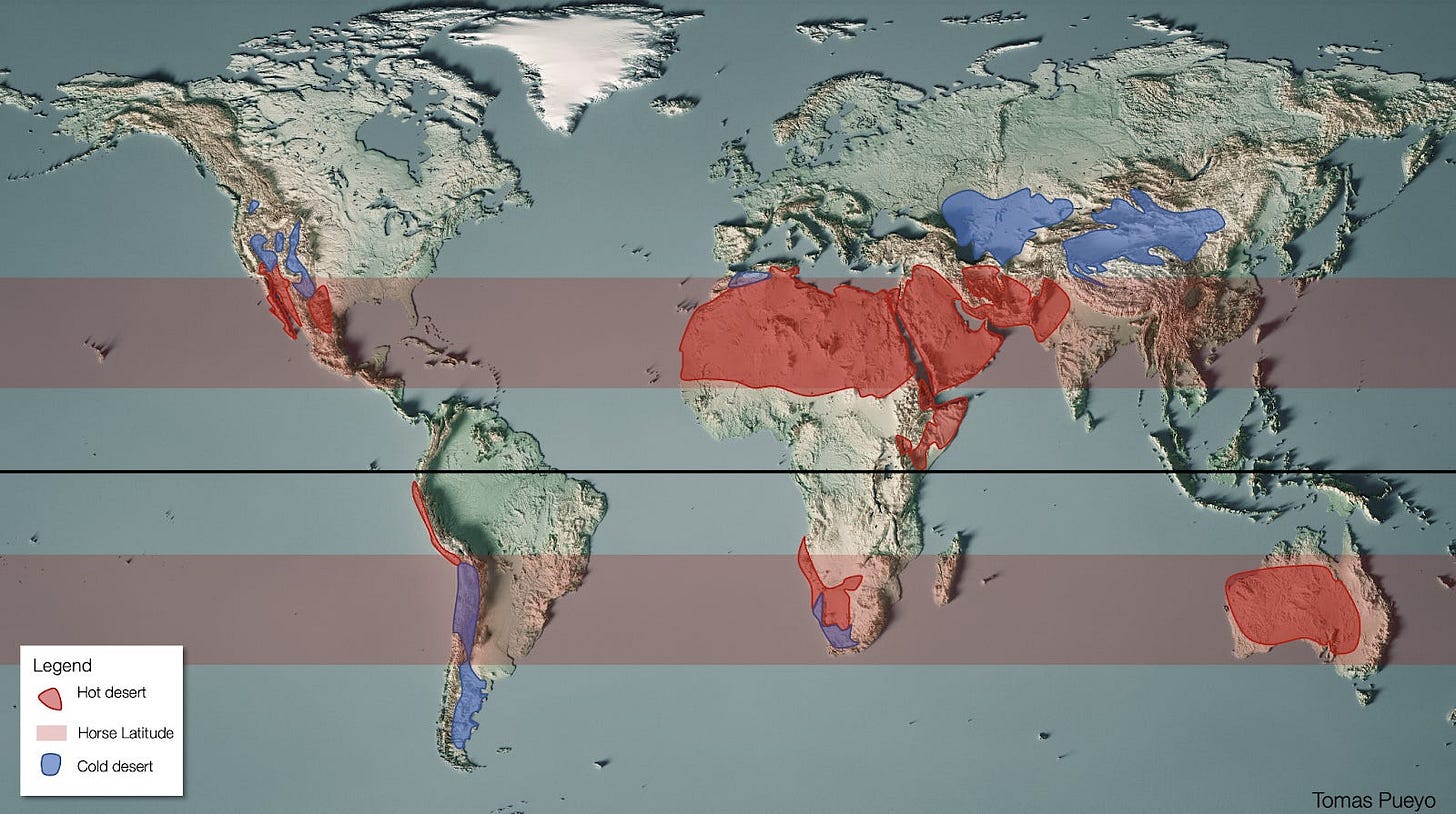

When there’s no rain, there’s no people. The Sahara, the Kalahari, and Somalia are empty. This is common in horse latitudes around the world, because of latitude and the atmosphere.

Ethiopia’s mountains catch the monsoon rains that would otherwise go to Somalia, so it’s cooler and rainier. That’s why it’s Africa’s 2nd most populous country.

The Rift Valley is the mountain chain that concentrates the most population in Africa... and it’s in the highlands.

The Maghreb in northwestern Africa is on the southern border of temperate regions. Mountains catch rainfall, and people live on them (as they’re more fertile) or on the coast, which is dry but includes the rivers from the mountains.

Egypt

Let’s zoom in a bit on Egypt, which as we know is just the Nile.

It’s farther south than most other big ancient civilizations, which makes it a bit of an outlier. It’s quite warm. But it’s also extremely dry because it’s in the horse latitudes. The dryness means no diseases, and no leaching of soil from excessive rainfall. You still get the problem of lower productivity because of the heat, but does it matter here?

The heart of Egypt is the Nile, and it spawned a hugely successful civilization because it has lots of water flowing through flatland and so it fertilizes itself! In How Rivers Shaped States, we saw how the annual flooding of the Nile swamped the riverbanks with water and sediment. This is also why a very strong state emerged, as it was so easy to calculate the potential for food production of every plot (just note the high water mark), that taxation was simple. Crucially, the land didn’t require much work at all. Only during some key periods, so the productivity cost that comes from heat was bearable. It’s also why, I assume, the Egyptians could build the pyramids: There was so little work involved in agriculture that, outside of harvest times, the state could recruit this surplus of labor for its vanity projects.

So I’d say Egypt corresponds quite well to our theory.

Congo

The Congo is another country that corresponds perfectly. It’s the 2nd biggest country in Africa, but only the 4th in population. It’s 37th out of 54 in population density, and that’s despite basically occupying the entire Congo river basin!

The Congo River is the 2nd biggest in the world by discharge, basically the Amazon River of Africa.

Yet no big civilization has ever emerged here. Of course, the logic is the same as in the Amazon: too much rainfall, too much leaching, soils are bad for agriculture.

And the endemic diseases are terrible. Hence why most of the population in the region lives on cooler mountains.

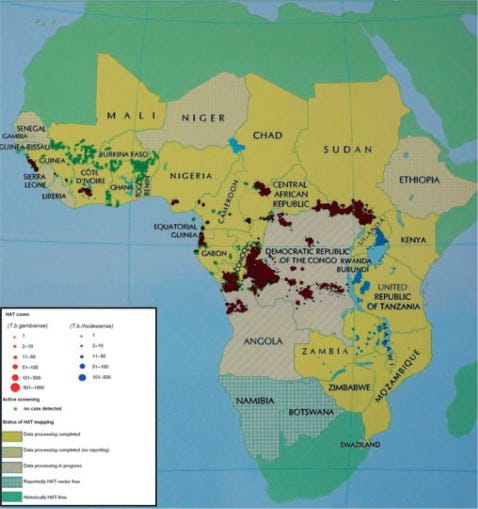

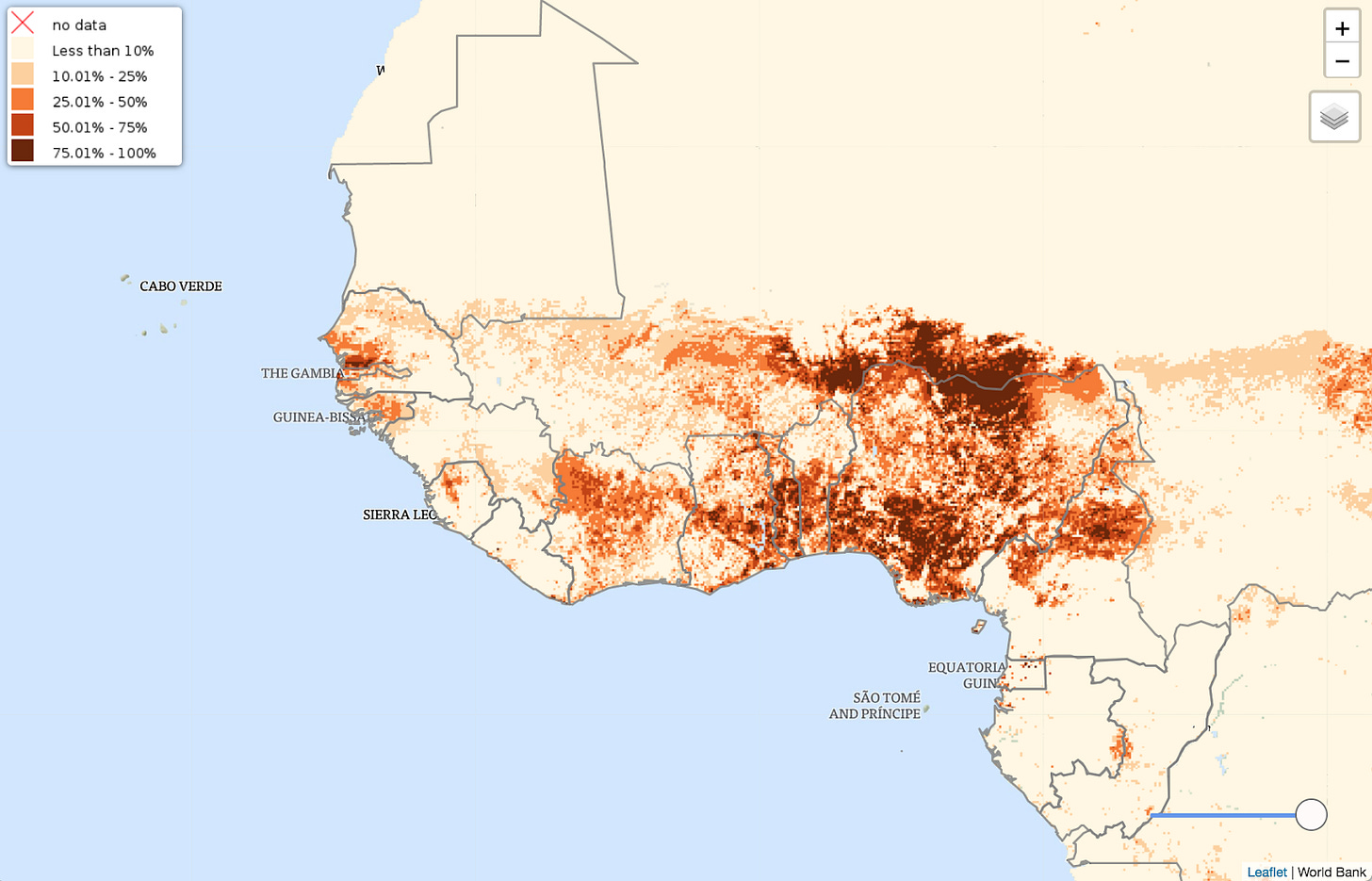

Now, adding malaria:

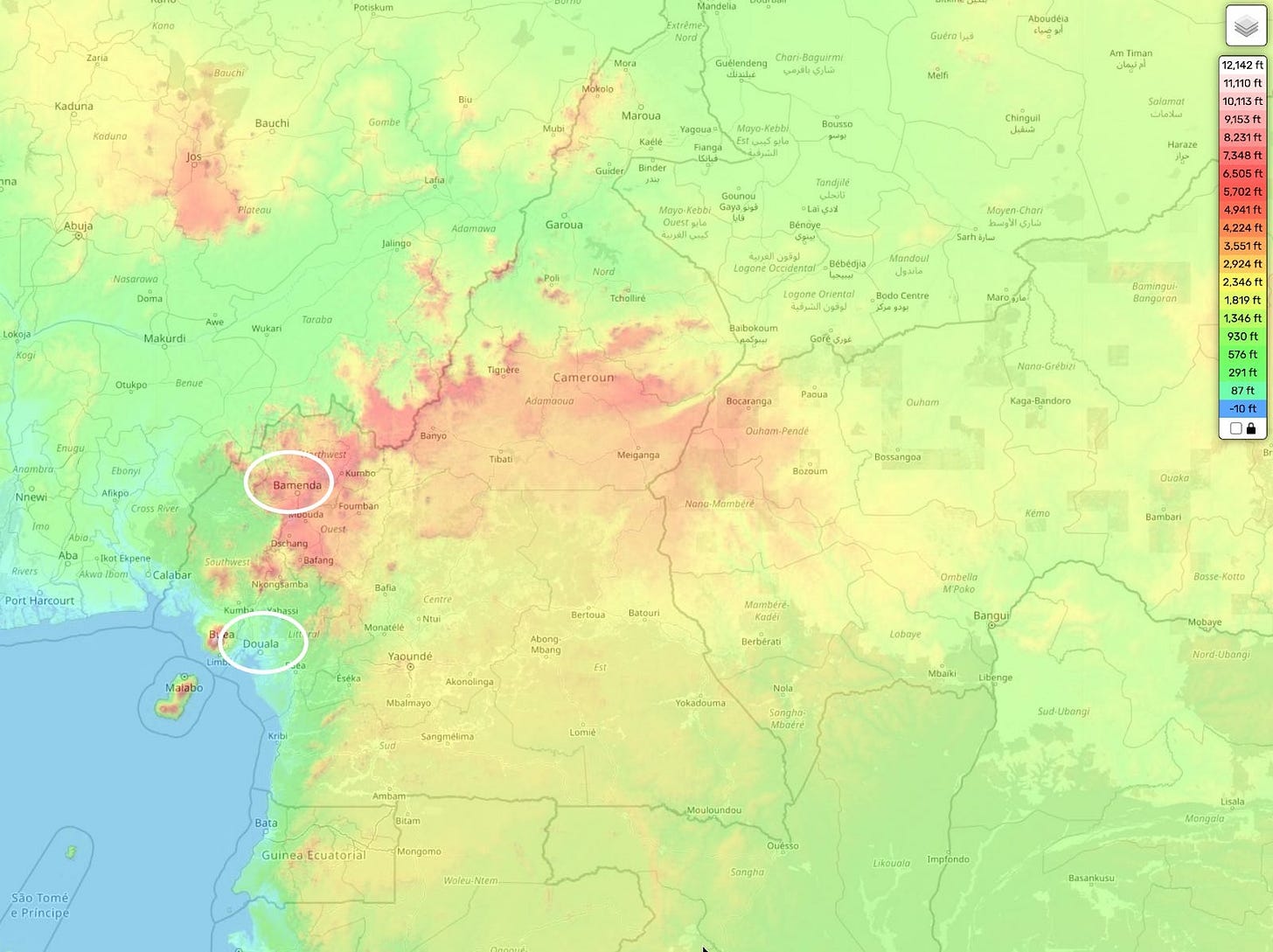

You can see most of the regions with big population centers tend to be in the mountains, where malaria is less problematic. The Congo is the most illustrative example, as it’s basically one big blob of malaria because it’s a large, low-lying, super wet, equatorial region. In comparison, the population centers in the highlands of the Rift Valley and Nigeria / Cameroon have the least malaria.

It is not the only disease. Here’s a map of trypanosomiasis, the sleeping sickness spread by the tsetse fly.

It thrives around the equator, especially in and around the Congo, and it doesn’t just incapacitate humans, but also big mammals. Spread by the tsetse fly, it kills essentially all horses and roughly 70–100% of cattle in the areas it inhabits.

Reader Rhea added this comment on Cameroon:

Douala, the metropolitan and extremely hot region, is considered lazier than the cooler mountainous city of Bamenda. I recall attending the state fair on a very hot day. I was exhausted and slow in mind and body. I recall a man telling my parents “it’s the heat, it affects the brain.”

So we’ve accounted for central Africa. There is, however, a big population center in a low-lying area of Africa that doesn’t fit our theory as well.

West Africa / Nigeria

This is West Africa:

As you can see, from south to north it changes from jungle to savanna, then Sahel, and finally becomes the Sahara desert. Thus, it’s not surprising to see high population density in the savanna, sahel, and northern jungle:

It is not so flat:

Most of the major population centers are on these highlands. Here you can see the corresponding croplands:

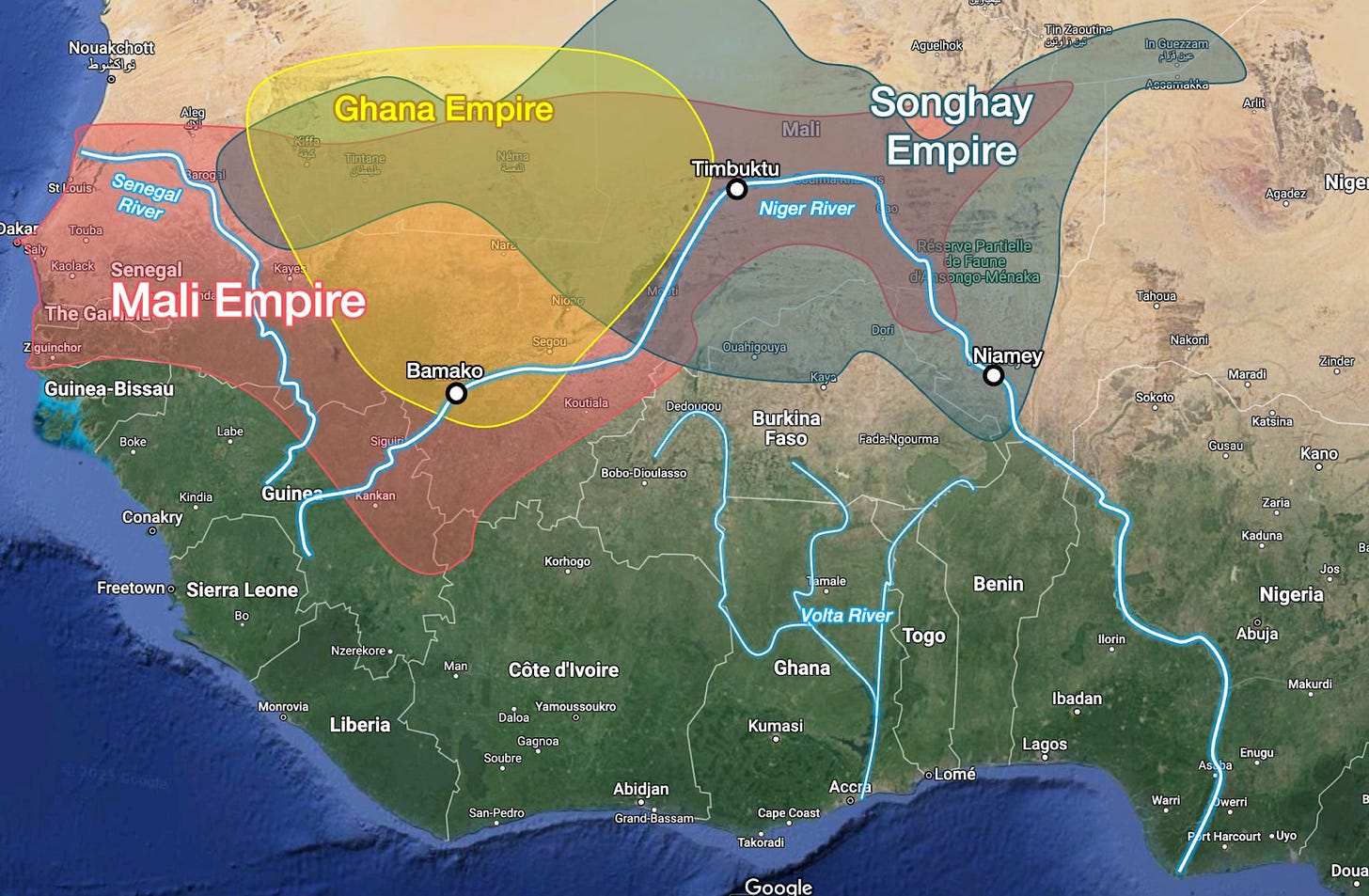

Although this region has been populated for quite some time, it was never as populated as other world regions, and has never created a significant, lasting empire. The most famous ones are these:

They were all built around the Niger River, which has an inland delta, in the savanna and in the Sahel. This prevented it from creating the type of structure that exists in Egypt, which gets a single continuous river that reaches the sea and never dries up. Instead, most of these empires’ economic booms were not due to agriculture, but to gold and slaves. When the gold ran out, so did the empires.

But when you look at the mouth of the Niger, you see this:

Here:

It rains a lot. The latitude corresponds closely to that of the hyperrainy Colombian Pacific region.

It’s flat and coastal.

Yet it has cropland.

And it’s hyperpopulated today.

That said, by far the biggest crop in Nigeria today is cassava, which comes from America, a clue that suggests the population of this specific delta was likely not as high in the past.

Here’s my guess as to why:

Historically, this region was not nearly as populated as others like Egypt, India, China, or Europe. This is why it has not generated any significant empire.

It’s very close to other regions that don’t have as much rainfall and do have large population centers, so it can always be replenished by people from elsewhere when famine or disease strikes.

At the mouth of the Niger, it receives a ton of sediment to fertilize the land, so it has some agricultural productivity despite terrible soil (because it’s old and leached by rainfall).

It gets a lot of rain, but seasonally, from the monsoon, which means it’s not battered by daily leaching rains like the Amazon or the Congo, allowing some of that fertilizer to be retained.

It’s still rife with tropical diseases, which have hindered its development in the past.

The heat, humidity, and nearby mountains have probably hindered its productivity, so its GDP per capita has never been high.

There’s one more thing that South America and Africa share.

Parts of both continents are very old, so their soil has been leached for eons, making it quite poor for agriculture. Yet another reason it was hard for big civilizations to emerge there.

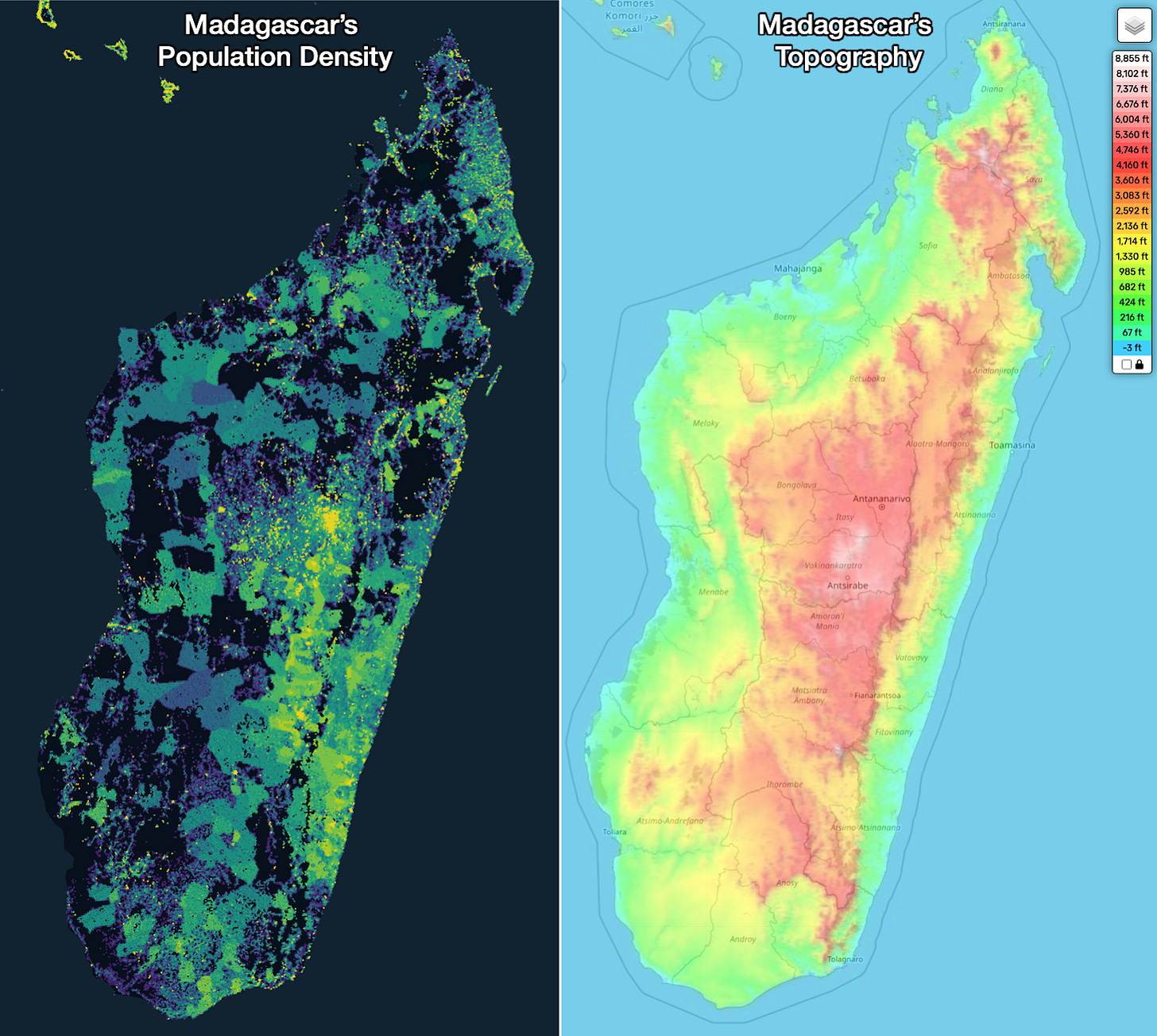

Madagascar

I’ve never mentioned Madagascar, but it’s a pretty good illustration of the dynamics we’re discussing, so here it is:

The highest density is in the mountains, there’s a secondary center of population on the windward coast (which gets more rain), and all regions are quite poor.

OK so I think we’ve got a good sense of what’s happening in Africa. Let’s move to Oceania, and then finally to Asia.

Oceania

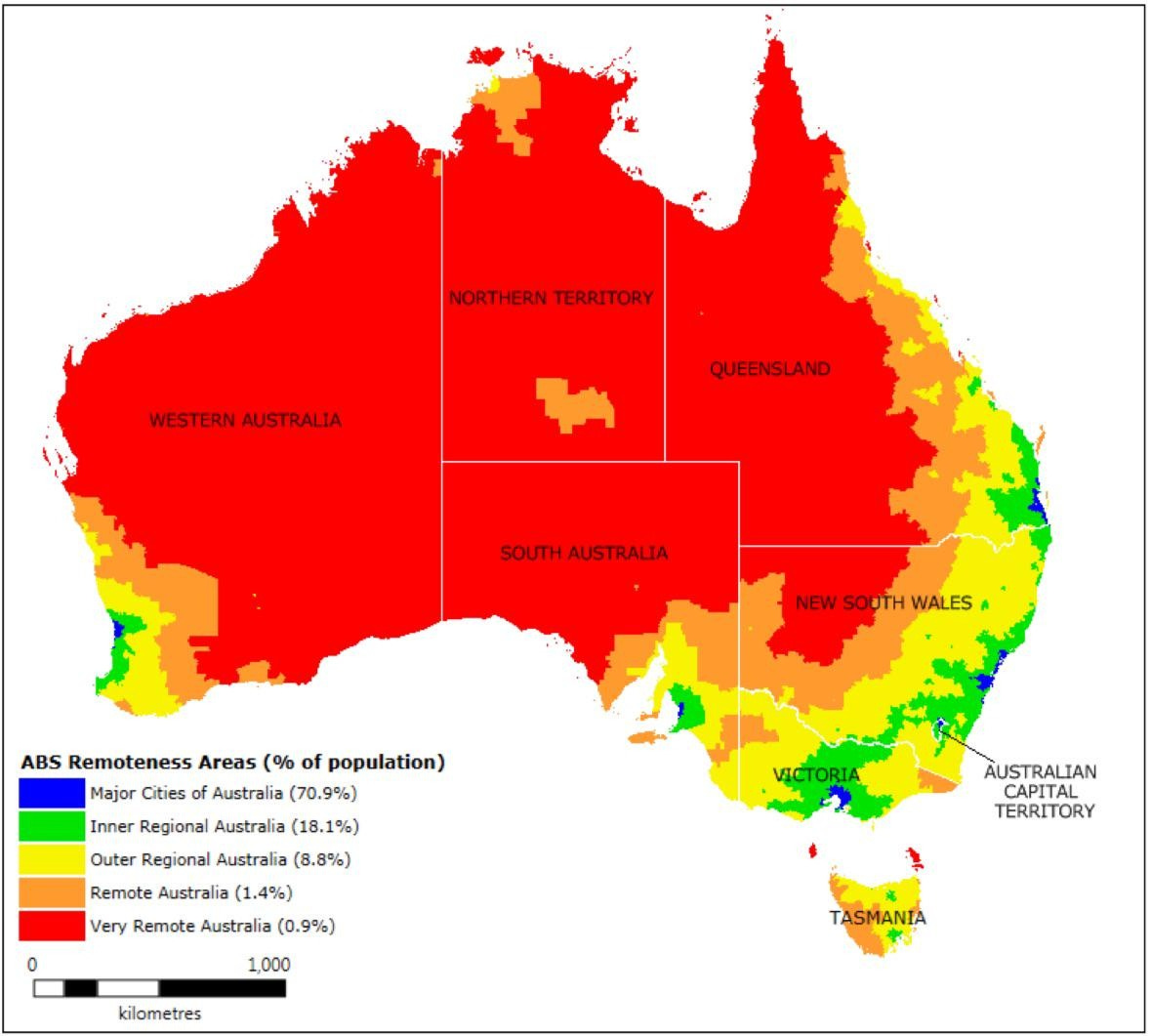

There are many examples here that illustrate our theory, starting with Australia.

Australia

From the previous article on the topic, from a commenter:

By area it is mostly a hot desert, but its institutions and GDP have flourished on its temperate southern coast and the entire country has benefitted from them.

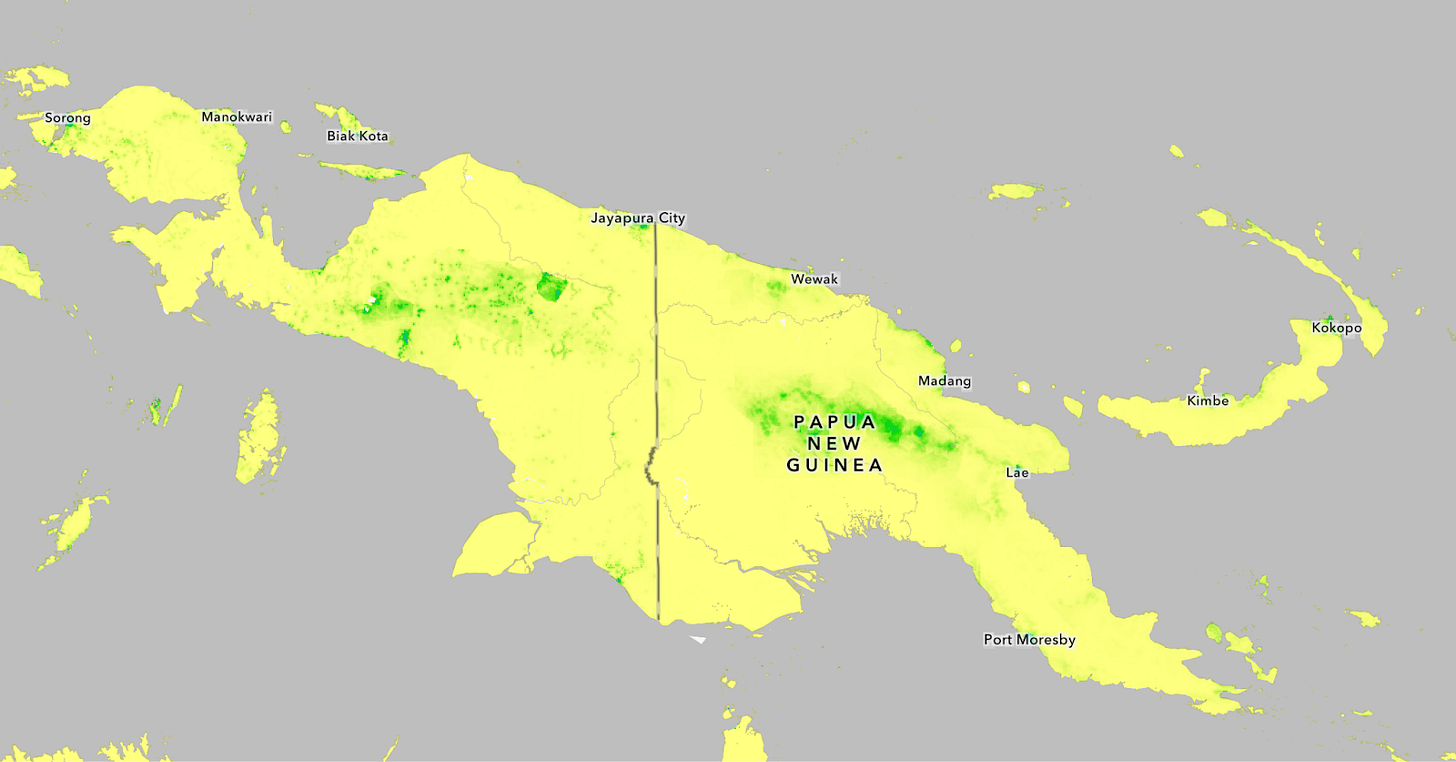

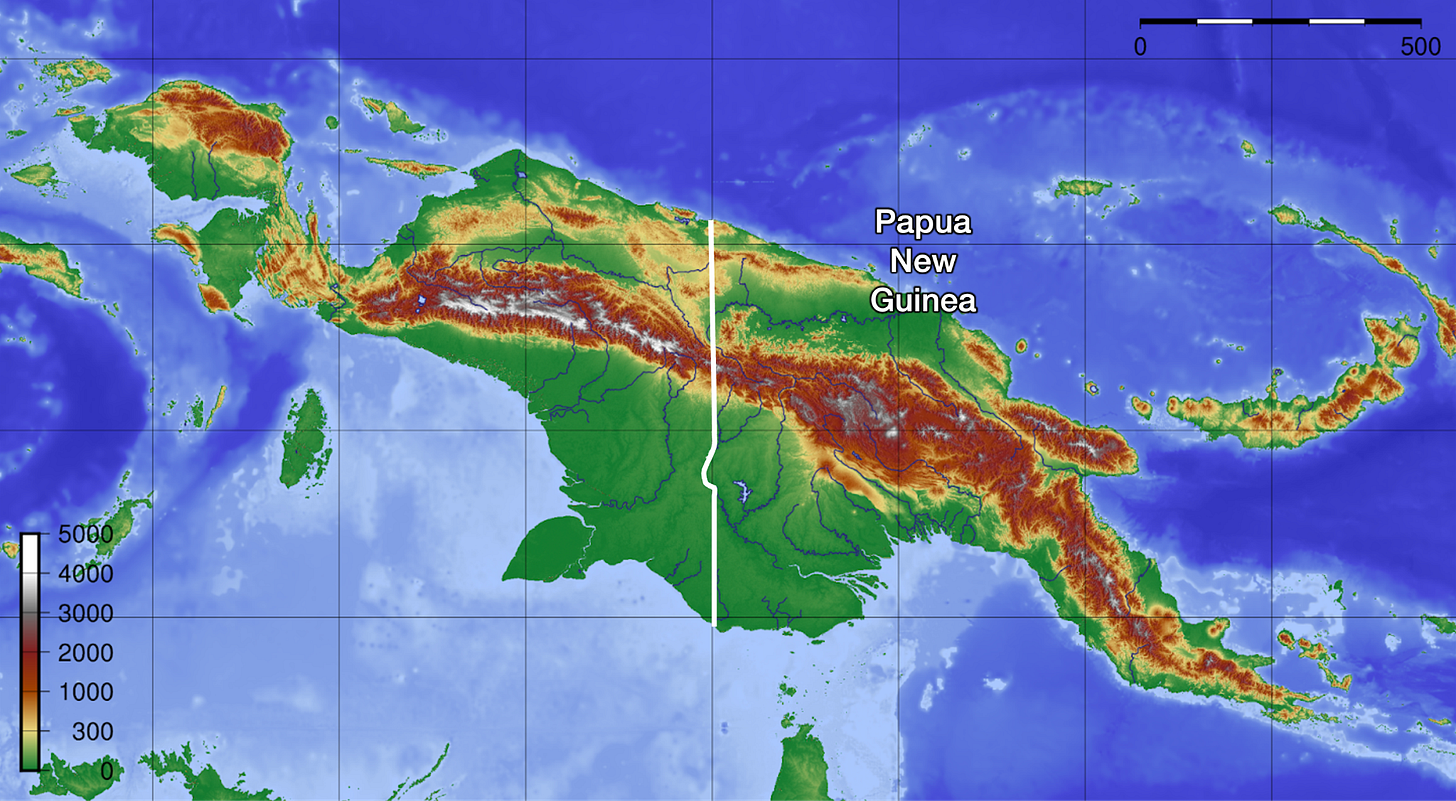

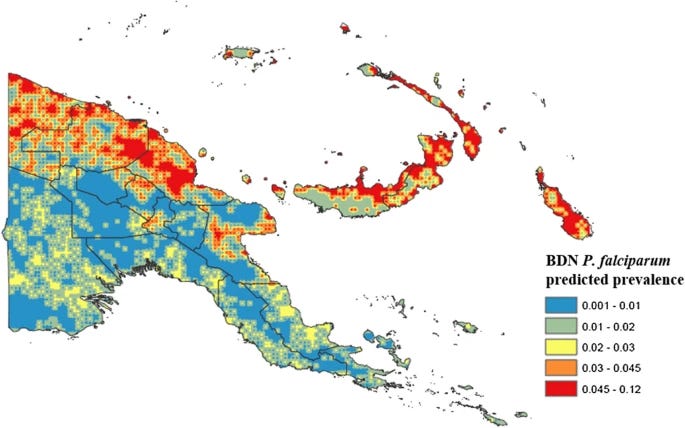

New Guinea

An equatorial island with flatlands and mountains down the middle. Where do people live?

Yeah, mostly on the mountains.

Malaria, however, is exactly where you’d guess.

New Guinea is also famous for its unbelievable diversity (hundreds of languages!) and its corresponding proclivity to conflict.

This is the poster child. New Guinea is tropical, mountainous, poor, multicultural, and prone to diseases in lowlands and conflicts in highlands.

But in the same region, there’s one big outlier that seemingly defeats the theory.

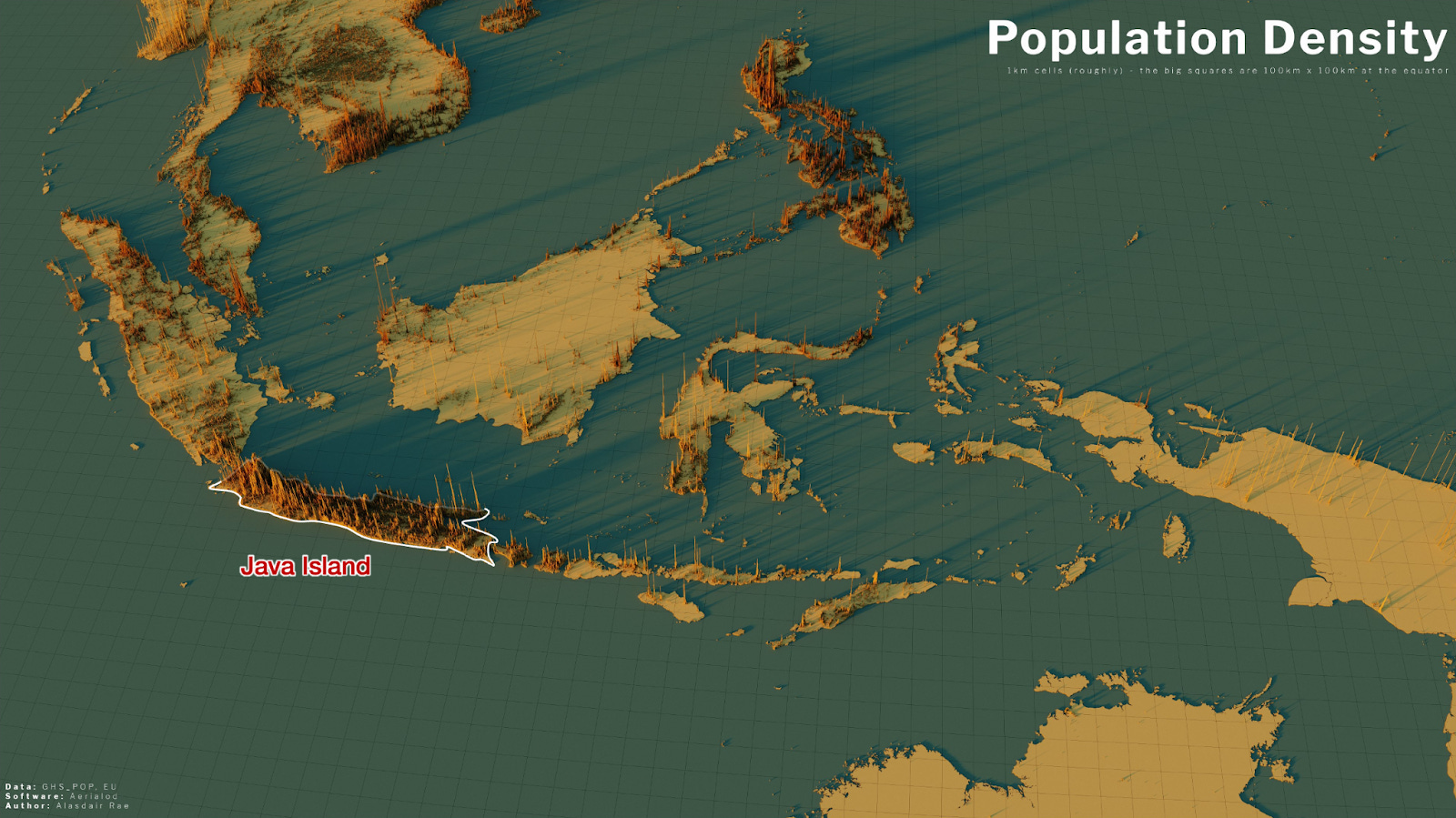

Java

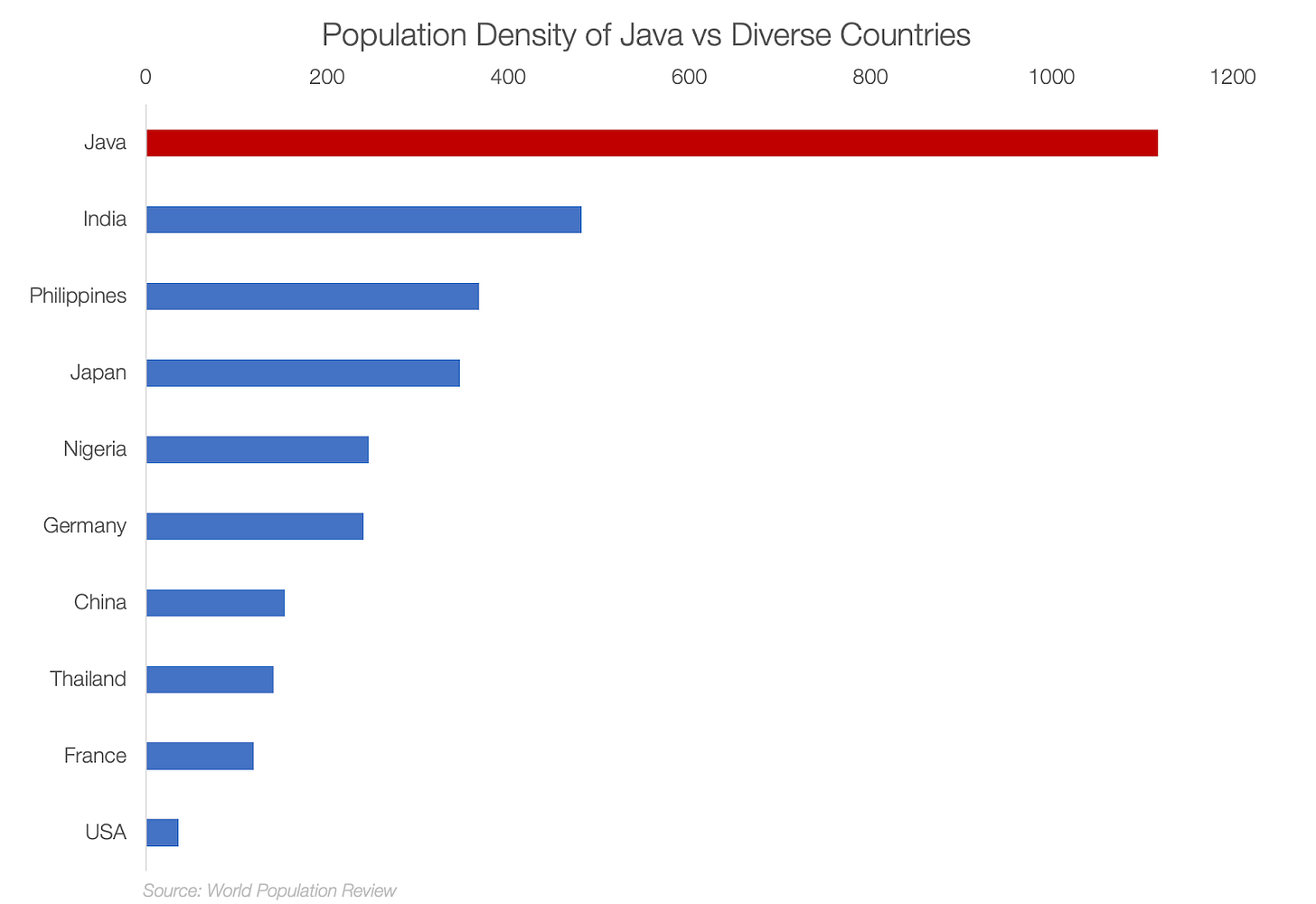

Java, with 156 M people, has a bigger population than Russia. From the article on the island:

Java’s population density is 1,100 people per square km.

This is 3x the density of Japan or the Philippines, 7x that of China, 30x that of the US. It’s nearly the density of Houston, Texas. For an entire island! With volcanoes!

Even weirder: Its neighboring islands in Indonesia are not that densely populated.

Compared to its biggest neighboring islands, it’s 8x more densely populated than Sumatra and 30x more than Borneo!

Why!? What made this island so special?

The answer is volcanoes.

Basically all the islands in the region are like Congo or the Amazon rainforest: They have massive amounts of rain leaching the soil, and they can’t easily farm anything. But the ash from Java’s volcanoes constantly fertilizes the soil there, making it incredibly productive.3

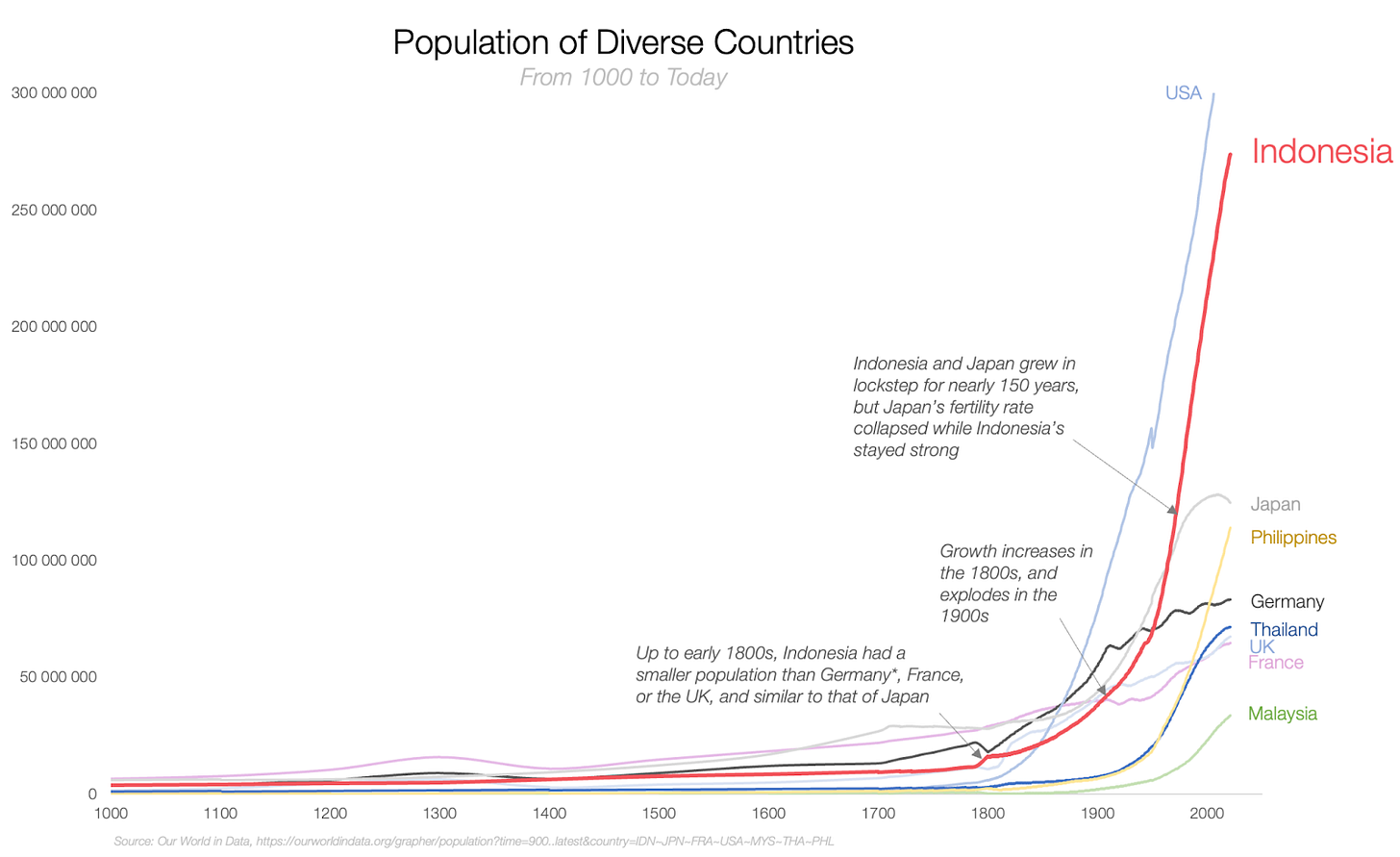

This is why it’s so populated today, but this is a reasonably recent phenomenon. Back in the 1800s, its population was smaller than Germany, France, or the UK.

This is also true of other countries like Thailand, Malaysia, or the Philippines (which also benefits from volcanic fertility, but without the equatorial leaching rains). In fact, it’s time for us to move on to the most important region, Asia.

Asia

We discussed in the original article on Mountains how Iran embodies the theory perfectly.

Iran

Turkey

But of course, neighboring Turkey also does. Its capital, Ankara, is at 1,000 m altitude (~3,000 ft).

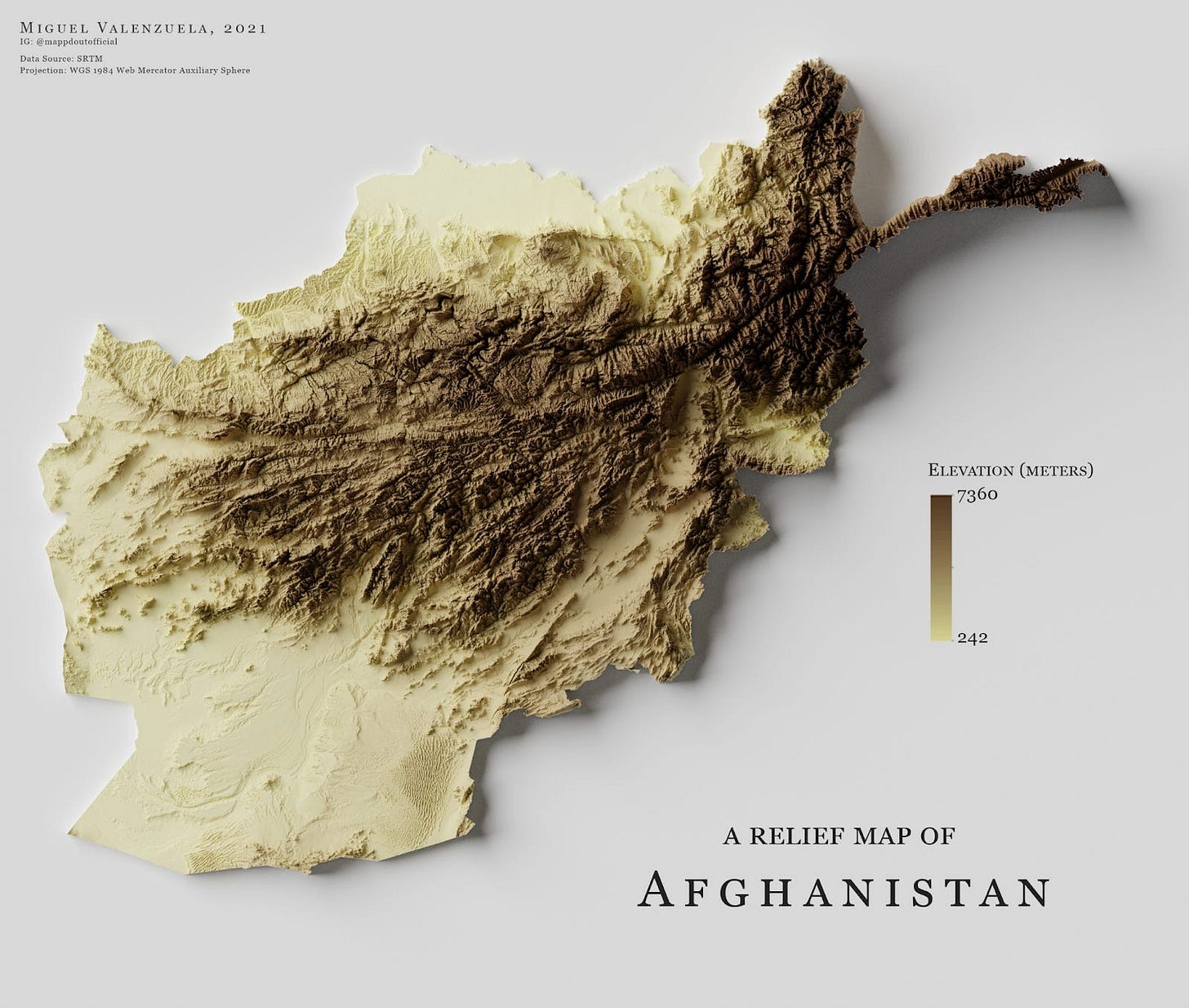

Afghanistan

Afghanistan never had a big enough population to create a strong local civilization because it’s too elevated and dry.

But it’s a good example of some of the dynamics we have discussed. Infrastructure is very hard. As a commenter said:

Seasonal rains have been known to completely destroy bridges—not destroying the bridge itself, but by washing out the approaches, leaving the bridge perfectly intact in the middle of a new wider river.

He also added that balkanization is intense here.

China

China is a poster child of our theories.

Its heartland is in the north—the perfectly temperate North China Plain. Over time, China conquered the south little by little. But the farther it went, the harder it was, as it confronted more mountains, mosquitoes, and malaria. It took the north a very long time to finalize dominion over the south, and even today, the mountainous Yunnan region has about 50M people, who are still ethnically different from the Han, and politically remote. In that region, you start seeing communities on plateaus that you don’t see in the north—like the capital, Kunming.

Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia are also quite informative.

Indochinese Peninsula

Lots of mountains and jungle here, but wherever you have a big valley with a river, you also have a decently-sized civilization today.

So it doesn’t look like this is close enough to the equator for populations to grow better in mountains. But also this region doesn’t have elevated plateaus, so we don’t have a counterfactual example. What we can tell, however, is that the farther south you go, the less population there tends to be:

The Malay peninsula, farthest south, is not very populated.

In Vietnam, the south has the Mekong River valley and delta, and they’re much bigger than the north’s Red River valley and delta. However, the Red’s valley is much more populated than the Mekong’s in Vietnam.4

The valley of the Chao Phraya in Thailand, which extends into Cambodia, is huge, yet in the past its population wasn’t as massive as China’s.

If we look at rains in the region:

It seems like a key condition is to not have rain year-round. The tip of the Malay Peninsula, like the islands of Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea, have rain year-round, and none are highly populated. We saw the same pattern in America (e.g. the Darién Gap), and Congo vs Nigeria.

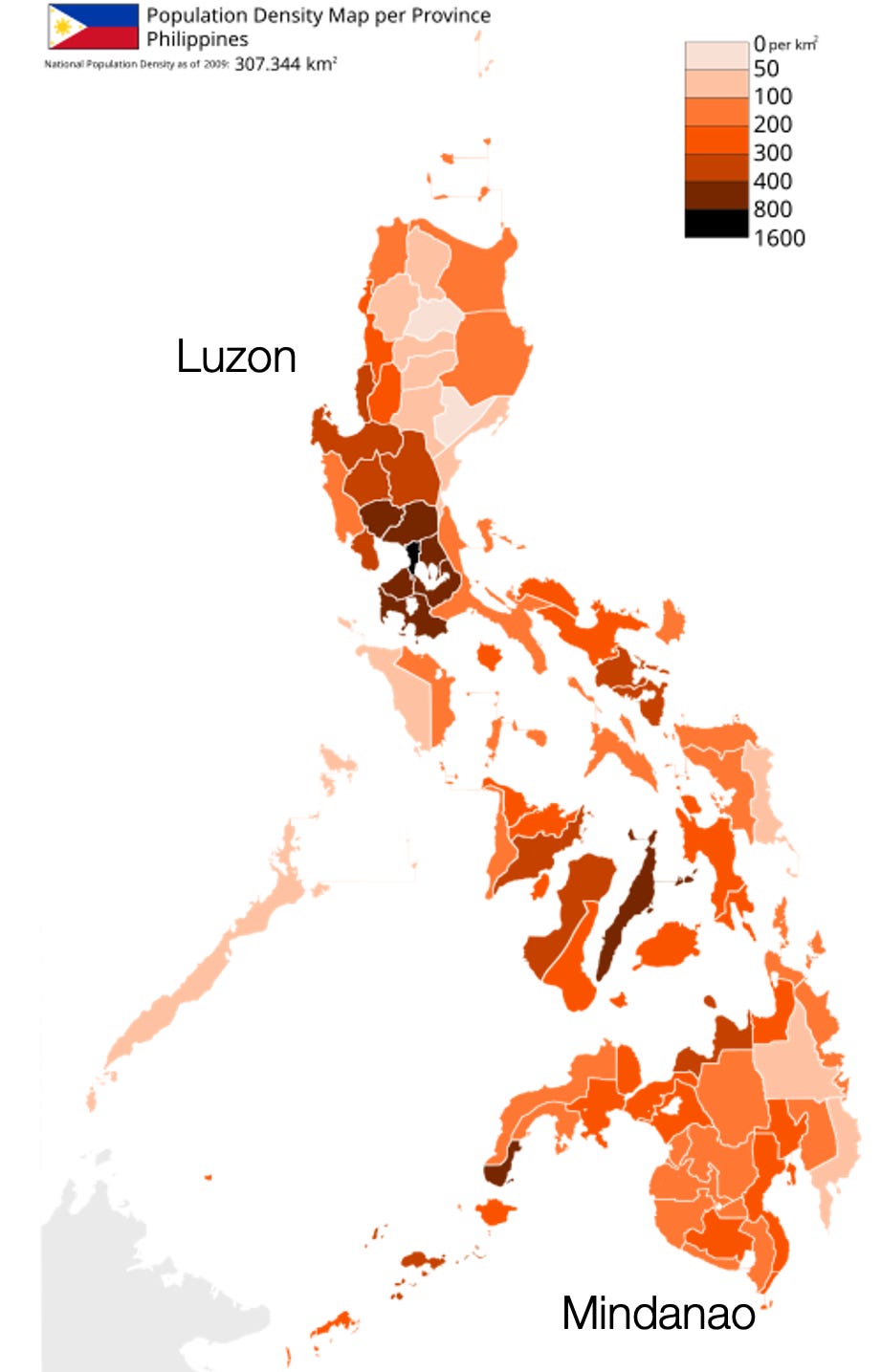

Interestingly, a similar pattern can be seen in the Philippines: The northernmost large island (Luzon) is much more densely populated than the southernmost large one (Mindanao). Within Mindanao, the least populated part is the east coast, which receives rains virtually all year long.

Also, we can see how Java is actually south enough to get at least some dry season across the majority of the island.

There have been a couple of empires in this region in the past, the Khmer in Cambodia, Siam in Thailand, Burma, and Vietnam. But most of these only emerged in the 1200s or later, and none had big populations. The Khmer, in Cambodia, emerged earlier, but their apogee was also in the 1200s, and its population didn’t even reach 1M back then (700k-900k). For comparison, Rome 1,000 years earlier had 60M-75M, similar to China’s and India’s. Egypt had 4-8M thousands of years earlier.

This leads us to our final destination.

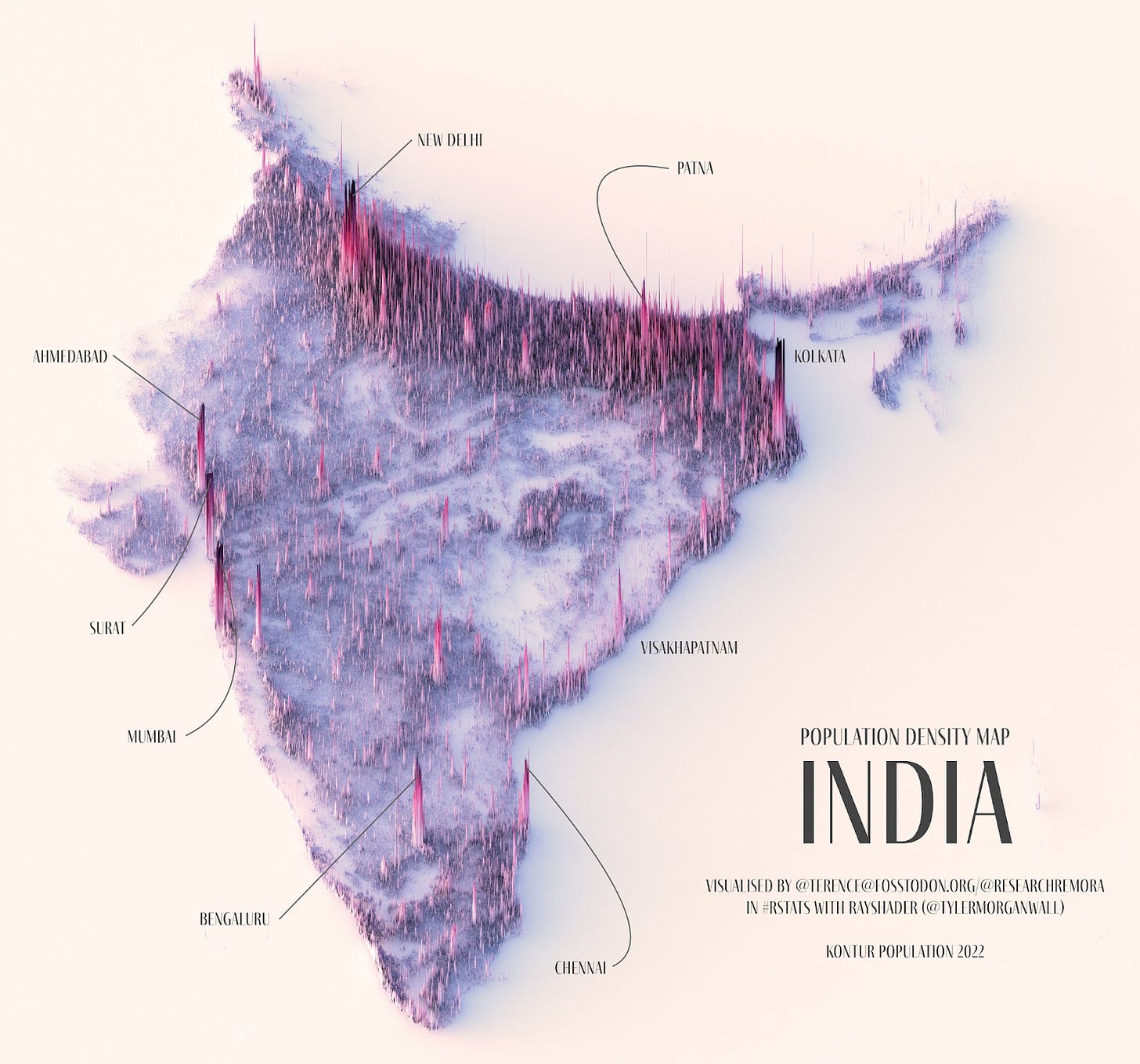

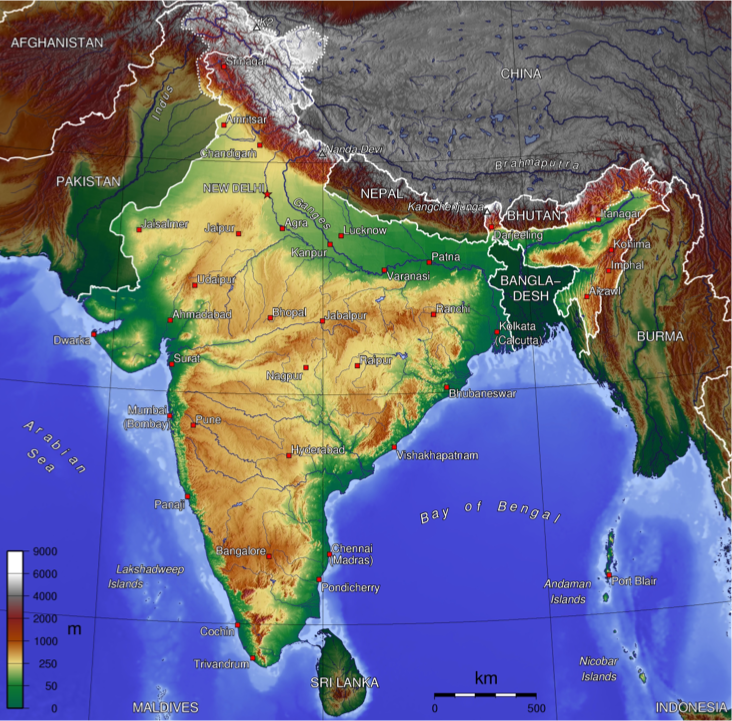

India

India is a mix of everything we’ve seen.

Most of the population is actually in the north:

It follows the Ganges River Valley. The population in the rest of the country is less dense. But it also tends to live more on mountains!

Bangalore, for example, one of the southernmost big cities in India, is 1,000 m (~ 3,000 ft) high.

Also, if you go back to the animation of rainfall throughout the year, you’ll notice the long annual periods of drought, which make sense since most of the country occupies similar latitudes to Arabia and the Sahara desert. But the drought periods are followed by the intense monsoon that then brings sediments down to fertilize the Ganges Valley. This wet-dry cycle reduces soil leaching and diseases.

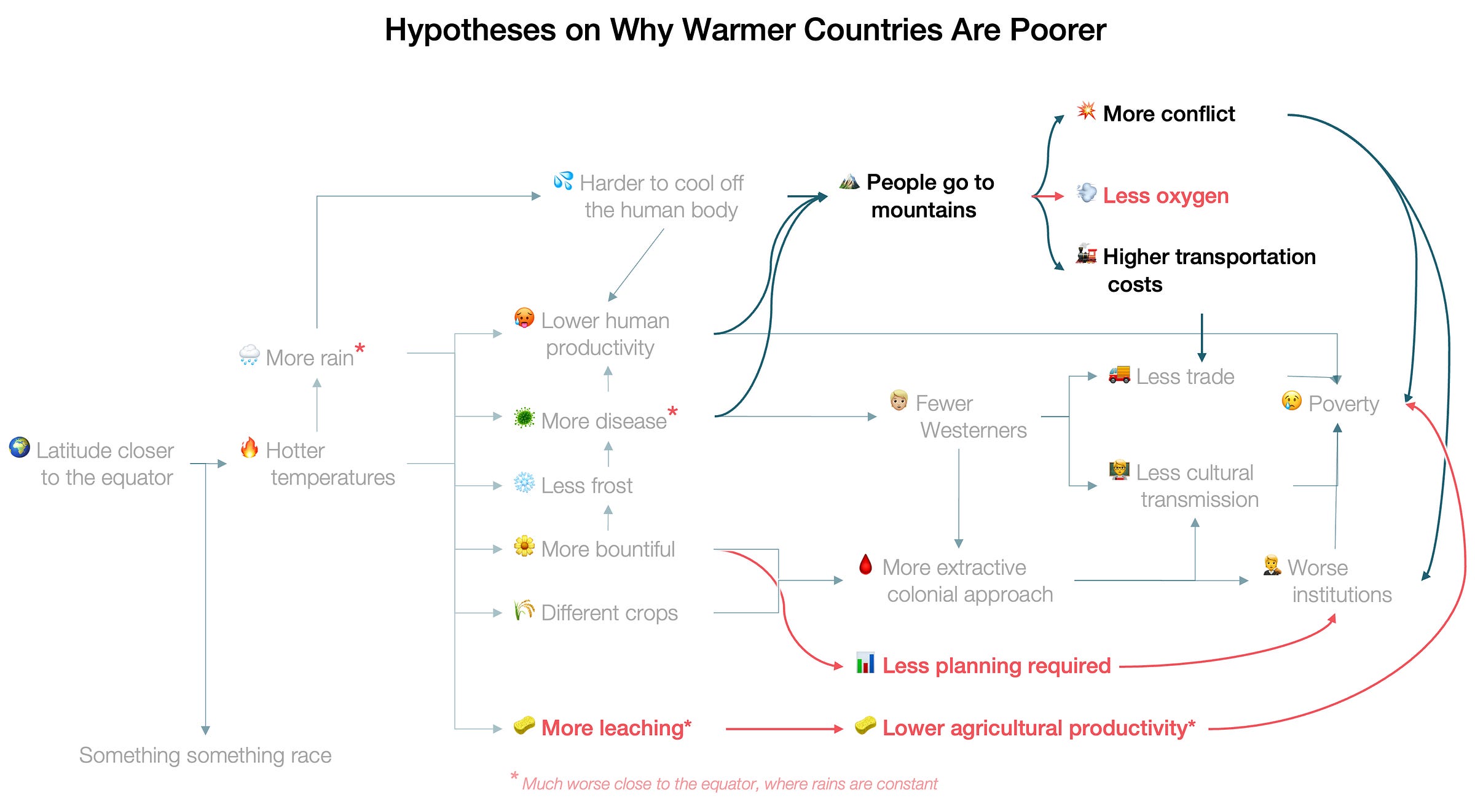

Let’s Update the Theory

If we summarize:

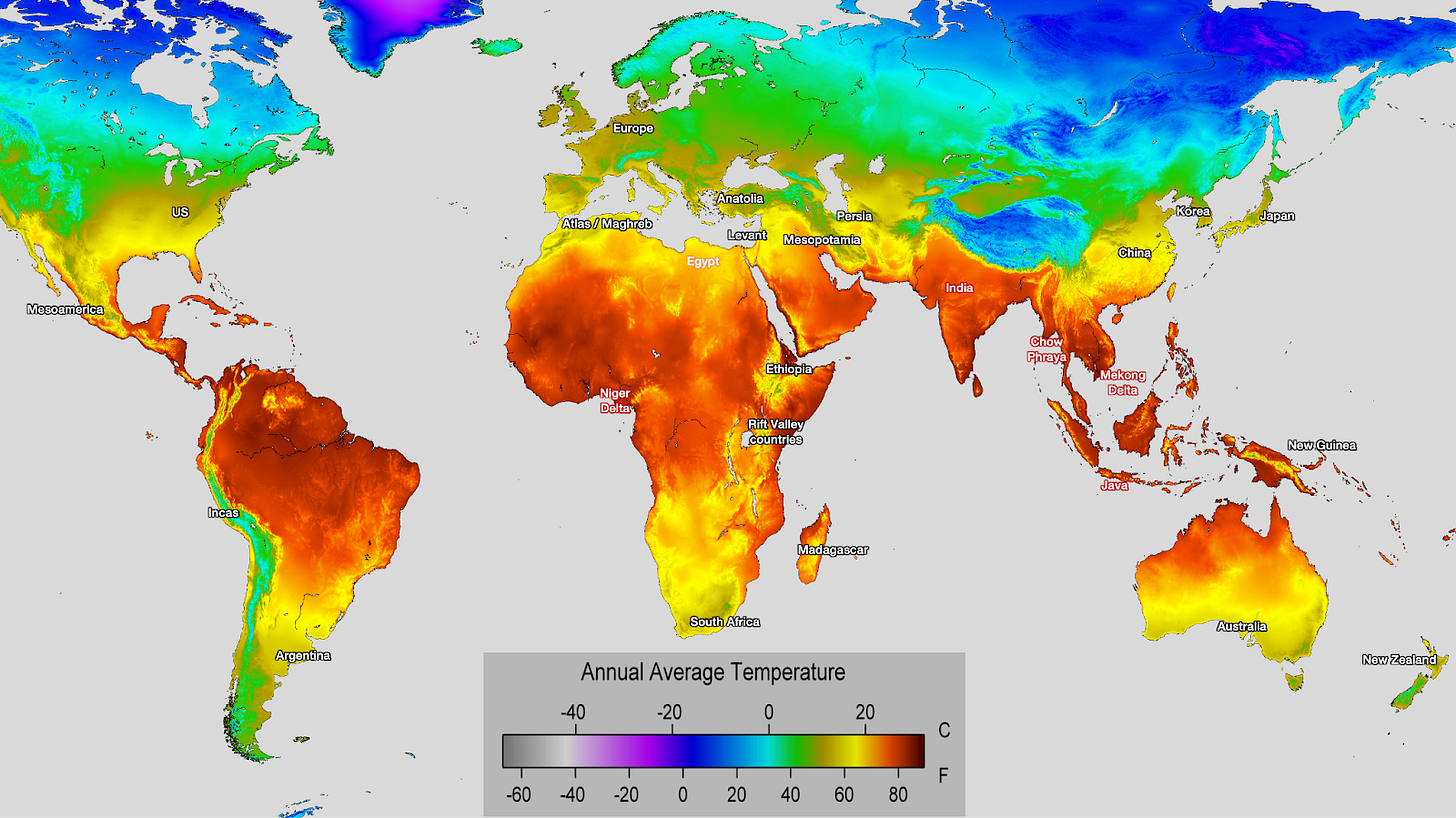

Temperate means population and wealth.

The most prolific societies have tended to develop in the yellow / brownish / green areas below: US, Canada, Mesoamerica, Incas, Argentina / Chile, Europe, the Atlas / Maghreb, South Africa, the Rift Valley, Ethiopia, Levant, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Persia, China, Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand…

Even in smaller countries, we see a similar pattern where people tend to live in cooler mountains than on the coasts, like Madagascar, Cameroon, and New Guinea.

Near the equator, there are few, poor people

This is because the intense, continuous heat produces intense, continuous rains, which in turn leach soils and cause disease. This is why populations and wealth have been very limited in the Amazon Rainforest, any low-lying region in Central America, the Congo, Malaysia, Indonesia, and most of New Guinea.

In my previous post, I had not noted the importance of constant rains and their consequence:

Lots of soil leaching, so little agriculture, so little food, and fewer people

Even more disease than elsewhere, imposing a productivity toll

Exceptions are rare and very telling. The main one is Java, which fights the leaching through volcano ash. Another is the Niger Delta in Nigeria, which seems to have developed recently, has a dry season, and is fertilized by the Niger’s sediments.

The transition between equatorial and temperate climates creates unique situations based on local conditions, so you have to pay attention

Here, there aren’t constant rains anymore, so leaching and disease are less prevalent. It’s still hot, so elevated plateaus in these regions did give birth to civilizations (e.g., Mesoamerica, Iran, Anatolia). But they aren’t necessary for civilizations to emerge:

Egypt is hot but it doesn’t have any leaching, and the burden of disease is low thanks to the year-long dryness of the environment. Fertilizer is brought by the Nile.

In Indochina, there’s more development as you move north. The southern tip gets year-long rains, and has very little population. All regions that developed have strong fertilization via rivers (which brought the sediments leached by the seasonal local monsoon). The civilizations that did emerge did so later, with smaller populations than in other regions, probably due to the harder conditions.

India has both a dry and a wet season. The north is the most populous. It also happens to have the Ganges (and the Indus in Pakistan), a great, year-long source of water and fertilization. The south is more mountainous, and the elevated regions are quite populated. My guess is that heat and disease burden have hindered the country along its history, even if not enough to stop it from becoming so populous.

This also brings us back to Malthus and the sources of wealth. Today, we’ve mixed GDP with GDP per capita, because of the Malthusian idea that more wealth meant more people. But this is not completely accurate.

Agricultural productivity used to be the determining factor of civilizations, because virtually all the economy was focused around food. So everything we said today is relevant broadly until the Industrial Revolution. For agriculture, heat and humidity are fantastic, but leaching and disease are not. This is why, until the 19th century, the poorer regions were those very close to the equator, where leaching and disease were the worst.

This also means there is a discontinuity in agricultural productivity: It’s really bad close to the equator, but the more humans escaped year-long rains—which happens around both tropics—agricultural conditions quickly improve. This is why wealth measured as people or GDP is more common in warm countries than GDP per capita.

That was before the Industrial Revolution. Afterwards, the productivity of agriculture matters less. And outside of agriculture, leaching doesn’t matter at all, but disease and human productivity still do. So temperature and humidity have hindered the rest of the economy. This has happened a lot directly, but also by pushing people to live in the mountains. This factor is more continuous than leaching though, so the farther from the equator, the better.

I would also like to add some theories from commenters, which I haven’t independently verified but sound reasonable:

Steven Weisz argues that more seasonal variance requires more planning, which in turns begets more human capital development to make it happen, and probably a more adapted culture and institutions.

Al MacDonald suggests that people living in the mountains have less oxygen, which might make it harder to exert yourself.

If we add up everything, this is what we get:

I hope you took advantage of the holidays to read and enjoy this massive article! Next week, we’ll be back to close 2025 with a retrospective of two topics we’ve explored during the year: Robotaxis and AI. I’m extremely excited about what comes next, which I’ll share very soon. In the meantime, merry Christmas and happy holidays!

And maybe a bit of the oil & gas regions of Russia.

Tellingly, the earliest predecessors to the Aztecs were the Olmecs, on the coast, but their civilization was never as rich or populated. Teotihuacan followed, and it was much bigger and powerful—and on the mountains.

Unsurprisingly, many of its biggest cities are nested around volcanoes, like Bandung or Malang.

I’m going to guess this is an underdiscussed reason why the north beat the south in the Vietnam War.

Your note on the Maya is incorrect. The Maya did not live as north as they could on the Yucatán peninsula.

The Maya had distinct phases. First, the classic Maya world developed primarily centered on the region of Peten, Guatemala, centered on the large lowland cities such as Tikal, Calakmul, and Palenque.

There were highland Maya but the civilization had its greatest prominence in the lowlands of northern Guatemala. The highlands were important as a source of obsidian, stone, and other resources.

Then the classic Maya collapse occurred, this center of civilization was reduced, and development began to shift.. not southward toward the Guatemalan highlands but northward. Cities such as Chichén Itzá were actually quite late in the span of Maya civilization but represent the location of the highest societal complexity of the Postclassic period.

There were different hypotheses about Maya population densities, with one end of the range holding that the lowland Maya world was among the most densely populated in the world at the time. Modern LiDAR research has found an astounding amount of infrastructure under the forest canopy, confirming the higher estimates as being more accurate.

Similarly, this technology is being applied in the Amazon and we are finding a surprising amount of lost cities and evidence of quite high population densities.

The Maya have been held as a great counter example to the idea that development to high population densities is impossible in tropical forest landscapes, and it does appear that much of the neotropics have these relict civilizations that provide similar challenges.

One might argue, well, they collapsed, however periodic collapse was more of a feature of all the civilizations in the American continent than an anomaly.

Overall I loved your posts on this topic and they’re very compelling. I’m somewhat considering doing a deep dive on this topic of rainforest civilizations as I have taken classes in Maya archaeology and this has long been one of my favorite subjects.

Human habitation does seem to follow the patterns you describe to a remarkable extent. But there are some quite significant counterexamples hiding below the forest canopy.

Great posting. Enjoyed reading it. This is a one-stop lesson in demographics . Should be recommended reading for each student.